There’s a lot of discussion about ‘is it a matter of individual responsibility?’ Let’s look at how much it costs to have a healthy diet. If you’re in the bottom ten per cent of household income, to follow the NHS healthy eating guidance you would have to spend 74 per cent of your income on food. Impossible. So to feed your children junk food is cheaper.

"To feed your children junk food is cheaper"

— BBC Newsnight (@BBCNewsnight) April 13, 2023

Sir Michael Marmot says the poor are stuck in a cycle of feeding bad food to their children#Newsnight pic.twitter.com/nmhs5CxVyr

The idea that the poor would have to spend three-quarters of their income to eat healthily has been doing the rounds in ‘public health’ circles for a few years, but this is the first time I’ve come across it in the wild. It should strike you as preposterous because healthy food is generally cheaper than ‘junk food’. ‘Junk food’ is usually tastier and always more convenient, but it is not cheaper than starchy carbohydrates, fruit and vegetables, which are the core components of the government’s Eatwell Guide.

The 74% figure comes from a self-published report from the Food Foundation. It takes an estimate of the cost of a healthy diet from a 2016 study in BMJ Open and compares it with unequivalised household income figures from the Office for National Statistics.

The optimised diet has an increase in consumption of ‘potatoes, bread, rice, pasta and other starchy carbohydrates’ (+69%) and ‘fruit and vegetables’ (+54%) and reductions in consumption of ‘beans, pulses, fish, eggs, meat and other proteins’ (−24%), ‘dairy and alternatives’ (−21%) and ‘foods high in fat and sugar’ (−53%). Results within food groups show considerable variety (eg, +90% for beans and pulses, −78% for red meat). The modelled diet would cost £5.99 (£5.93 to £6.05) per adult per day, very similar to the cost of the current diet: £6.02 (£5.96 to £6.08).

Are we then to believe that people in the bottom income decile are already spending 74 per cent of their income on food? That can’t be right as they are only spending about 21 per cent of their income on food and alcohol combined. And although food prices have risen since 2020, the share of income spent on food and non-alcoholic drinks by households in the bottom quintile is still below 20 per cent.

So what’s going on?

Based on the figure of £5.99 a day, the Food Foundation assumes that £41.93 is the weekly cost of a healthy diet for an adult and it makes various adjustments to estimate the cost for partners and children. Fine.

It then uses a slightly lower figure of £36.37 a week as the cost of the average diet. I’m not sure why they don’t use the figure from the BMJ Open for this (well, I can guess), but it still isn’t a huge difference: an extra £5.56 a week or 15 per cent more. This isn’t enough to declare that having a healthy diet is “impossible” even at the lower end of the income distribution, as Marmot claims.

What about the income data? Marmot doesn’t mention it, but the Food Foundation figure is based on disposable income. Moreover, it uses a rather expansive definition of disposable income which does not just exclude income tax, national insurance and council tax, as would be normal, but also excludes rent, mortgages, service charges and water bills.

This removes a large part of people’s incomes in one fell swoop. Housing costs alone take up nearly half the income of people in the bottom decile so you can halve the figure Marmot gives straight away. (If you want to get angry about prices, I suggest you focus on housing.)

The Food Foundation also explicitly ignores free school meals which make up a non-trivial proportion of the diet of low income families.

For example, we estimate that a household of four (two adults and two children aged 10 and 15) would need to spend £103.17 per week to be able to follow the Eatwell Guide.

On average, the poorest half of households in the UK would need to spend close to 30% of their disposable income to meet the government’s dietary recommendations.

This is where it gets slightly murky. Economists who work with income data treat very high and very low figures with scepticism. In this instance, the bottom two per cent apparently have no disposable income at all. In fact, their disposable income is negative. In a modern welfare state, this is rather unlikely. It is possible to imagine a situation in which a few people end up in this situation, but they would be so down and out that they are unlikely to come to the attention of the Office for National Statistics. A more likely scenario is that they are mostly wealthy people who are not eligible for benefits and living off savings (retired people under the age of 65, for example).

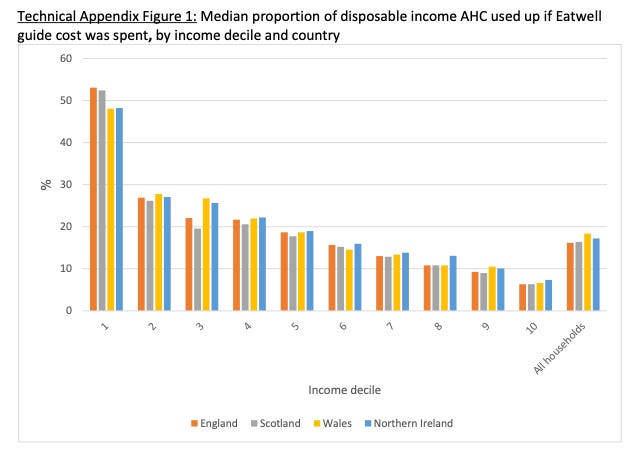

When calculating the proportion of disposable income that the Eatwell cost comprises, two percent of all households in the FRS dataset, comprising nearly 20 percent of households in income decile 1, had a negative disposable income AHC. To enable us to calculate the proportion of disposable income that would be used up by the Eatwell cost, these households were set to 100%.

This still seems high when compared to the neighbouring decile, and there are other reasons to be sceptical about figures from the very bottom end of the income distribution, but given the exclusion of free school meals and housing costs, it is not totally implausible.

But even using this questionable methodology, the cost of an average diet already takes up 44 per cent of the bottom decile’s disposable income and if we use the figures from the BMJ Open study, it takes up 51 per cent, i.e. exactly the same as the ‘healthy diet’.

Whichever you slice it, the difference in price between a ‘healthy’ and ‘unhealthy’ diet is either small or non-existent and the idea that the poorest tenth of households would have to have to spend 74 per cent of their income to afford it is patently false. Even if we assumed that a healthy diet was as expensive as the Food Foundation claims, the true figure would certainly be below 40 per cent and probably below 30 per cent.

There are lots of reasons why people on low incomes - or high incomes, for that matter - would prefer ‘junk food’ and takeaways to the food recommended in the Eatwell Guide, but price is rarely one of them.

No comments:

Post a Comment