If you say that a certain activity costs society £10 billion a year,

most people would assume that if that activity disappears, society will

save £10 billion a year.

They might have different ideas of

what ‘society’ means. Some will assume that the £10 billion is a cost

to taxpayers while others will assume that some of the cost is borne by

private individuals and businesses. But the majority will, quite

reasonably, assume that the cost is to other people, i.e. those who do not participate in the activity.

And

nearly everyone will assume that the £10 billion is money in the

conventional sense of cash that can be exchanged for goods and services.

But

when it comes to estimates from ‘public health’ campaigners about the

cost of drinking/smoking/obesity, all these assumptions would be wrong.

Most of the ‘costs’ are to the people engaged in the activity and they

are not financial costs. Taxpayers would not pay less tax if they

disappeared. In general, they would pay more.

Last month I mentioned an estimate of the ‘cost’ of gambling in the UK and said:

These

studies have no merit as economic research. They are purely driven by

advocacy. The hope is that the average person will wrongly assume that

the costs are to taxpayers and agitate for change.

The

main aim of these Big Numbers is to convince the public that

heavily-taxed activities place a burden on society that exceeds the tax

revenue, thereby justifying yet more taxes and prohibitions.

In

the case of smoking, this has become more and more difficult. Smoking

has been a net gain for the Treasury ever since King James I started

taxing it heavily in the 1600s. Today, as the smoking rate dwindles and

tobacco duty rises ever higher, anti-smoking campaigners have got their

work cut out duping non-smokers into thinking otherwise.

Tobacco

duty brings in about £12 billion a year. For years, groups like Action

on Smoking and Health (ASH) used a figure of £13.74 billion as the ‘cost

of smoking’. This came from a flimsy Policy Exchange report

which included £5.4 billion as the cost of smoking breaks and £4.8

billion as the cost of lost productivity due to premature mortality.

Neither of these are costs to the taxpayer. They are not even external

costs, i.e. costs to non-smokers.

Last year, in a review commissioned by the Department of Health,

Javed Khan came up with a figure of ‘around £17 billion’ as the

‘societal cost’ of smoking. This included ‘reduced employment levels’

(£5.69 billion) and ‘reduced wages for smokers’ (£6.04 billion). Again,

these costs fall on smokers themselves and are not external costs. They

are, in other words, none of the government’s business.

Last week, a report commissioned by Action on Smoking and Health (ASH) pulled out all the stops and announced that the cost of smoking to Britain was now - wait for it! - £173 billion. Go big or go home, eh?

This

is so far adrift from earlier estimates that even the casual observer

might start to smell a rat. The report was written by Howard Reed of

Landman Economics who used to do work for the people who campaigned

against fixed odds betting terminals. He has previously produced a report for ASH

claiming that smoking leads to unemployment and low wages, based on the

simple observation that smokers are more likely to be unemployed and

earn low wages. It is well known that smoking is far more common in

lower socio-economic groups, but it is an absurd leap of faith to assume

that smoking is the cause of unemployment and low wages.

Reed

nevertheless assumed causality and, in his new report, reckons that

smoking-related unemployment and low wages cost society (i.e. smokers)

£15 billion a year.

But that is nothing compared to the £123.7

billion he attributes to the ‘cost of early deaths due to smoking’. He

doesn’t show his workings for this calculation - or any other - but it

is a combination of all the hours that could have been worked if smokers

didn’t die prematurely plus the intangible costs of their lost years of

life.

The savvy reader will have noticed that all these ‘costs’

fall under the category of None Of The Government’s Damn Business. If I

die at the age of 75 rather than 80, I will lose the intangible benefits

of five years of life, but that is my problem. Similarly, if I retire

five years early and lose five year’s income, that’s up to me.

The

absurdity of portraying lost years of life as a societal cost - let

alone as a financial cost - can be illustrated by the example of

contraception. The contraceptive pill has prevented billions of years of

life, but it is very difficult to argue that it has cost society

trillions of pounds. A society doesn’t become richer just because more

people live in it; that’s why we use per capita GDP as the measure of national output, not overall GDP.

Certainly

there are intangible costs to dying prematurely, but these costs fall

on the individual. Moreover, there are intangible benefits to smoking

which reports like this never acknowledge. Since both the intangible

costs and the intangible benefits fall squarely on the smoker, it is for

the smoker to decide whether the costs outweigh the benefits. It is no one else’s business.

The

‘societal cost’ figure of £173 billion is designed to make it look as

if it is everybody’s business, but it is so obviously suspect that ASH

haven’t been using it in their PR. Instead, they have focused on a claim

from the same report that smoking imposes a net cost on taxpayers of

£9.5 billion.

This

estimate doesn’t include the bogus lost output or the intangible costs.

It is more relevant to policy and it takes into account the taxes

smokers pay on their tobacco. But is it plausible?

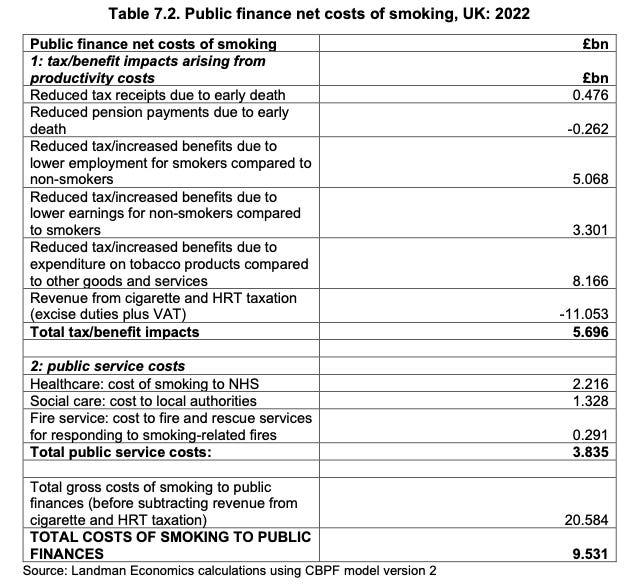

The figure breaks down as follows…

Reed

says that tobacco duty (plus VAT on the duty) rakes in £11.05 billion

(it is actually more than £12 billion but never mind). The challenge is

for him to find costs to the taxpayer that exceed this.

First,

he conjures up £8.4 billion in welfare benefits handed out to smokers

to compensate them for their higher levels of unemployment and lower

rates of pay. This hinges on the conceit that smokers are paid less and

are more likely to be unemployed because they

smoke. Whilst it is possible to imagine a scenario in which this could

be a factor for an individual (largely thanks to ‘public health’ groups

demonising smoking), it is very unlikely to be a general rule. A toilet

cleaner is not going to be paid more just because she quits smoking and

someone on the dole is not going to get a job just because he quits

smoking.

Secondly, Reed reckons that the government would

make an extra £8.2 billion if all the money spent on tobacco was spent

on something else. It is true that this money would not disappear. It

would be spent on other goods and services and some of those goods and

services would be taxed, albeit at a much lower rate than tobacco is.

There

would also be a multiplier effect of some kind which Reed assumes would

create more jobs than expenditure on tobacco does. He says that

“employment in the tobacco industry in the UK is close to zero”,

although a footnote says that 5,000 people work in the industry. He then

claims that tobacco retail and distribution “supports relatively few

jobs in the supply chain”, which will be news to people who work in

convenience stores.

Based on previous work he did for ASH,

Reed estimates that if smokers stopped smoking and spent the money on

all the things nonsmokers spend their money on, it would create more

jobs and the government would make/save an extra £8.2 billion in

taxes/benefits. He doesn’t show his workings so it is difficult to say

how credible the estimate is, but there are two things to bear in mind.

Firstly,

the revealed preferences of smokers shows that they would rather spend

part of their income on tobacco than on anything else.

Secondly, jobs are a cost not a benefit.

Societies

get richer by having the same things made by fewer people. What is

being proposed here is having other things made by more people. Whatever

those other things are, they are of less value to smokers than tobacco.

Thirdly,

there is £2.2 billion in healthcare costs and £1.3 billion in social

care costs. Fair enough, but what would these costs be if no one smoked?

That is the relevant question and there is lots of evidence built up over decades

that the costs would be higher because there would be more (mostly old)

people requiring healthcare. Reed is aware of this but explicitly

ignores it, more or less admitting that it would spoil his party if he

took it into account.

Sometimes it is argued

that in cost benefit analyses of policies which result in a reduction in

the number of premature deaths in the population (such as tobacco tax

increases or tougher tobacco regulations), the additional end-of-life

healthcare costs incurred by the people who live longer should be taken

into account. In the 2010 version of this model we argued that, even if

this were the case, it would be a mistake to include these costs in the

cost-benefit analysis (CBA) because there is a fundamental

methodological flaw in this approach.

Taken to its logical

conclusion, the inclusion of end-of-life healthcare costs in CBAs of

this type would lead to the perverse conclusion that policies which

result in larger numbers of premature deaths in the population have a

positive benefit to society because they reduce healthcare expenditure

on elderly people.

Yes it would! Because that’s what would happen!

The

whole point of this calculation is to estimate the impact of smoking on

the public finances, but as soon as it becomes clear that the

government would save money from the healthcare budget, Reed has to turn

a blind eye because it would lead to a ‘perverse conclusion’, i.e. a

conclusion that would not suit the agenda of the people who commissioned

it.

Reed is not even consistent in this. Elsewhere, he estimates

that smoking saves the government £260 million a year in reduced pension

costs due to premature mortality. Why include these savings but not the

health and social care savings? Both are equally macabre insofar as

they rely on people dropping dead.

(£260 million is a

massive underestimate, by the way. The government spends £110 billion a

year on state pensions. It is ridiculous to pretend that it would only

spend an extra 0.2% on them if no one had ever smoked. When Mark Tovey

and I conducted our own study in 2017 we found that the government would be spending an extra £9.6 billion on pensions if no one smoked.)

But whilst he won’t include healthcare expenditure foregone as a result of premature mortality, Reed does

include £476 million in tax revenue foregone as a result of premature

mortality. In other words, he thinks it is fair to include the taxes a

smoker would have paid if they had lived longer, but it is not

reasonable to include the healthcare they would have used - healthcare

that would have been paid for, at least in part, by those very taxes.

This

is economically illiterate nonsense that doesn’t stack up even on its

own terms. Perhaps that is unsurprising when you consider that an

anti-smoking pressure group not only commissioned it but helped to set

its parameters.

The Model was commissioned by, and developed in collaboration with, ASH.

But

it doesn’t really matter how the figure is arrived at because almost no

one will read the report. All that matters is that ASH have a Big

Number to cite when it’s lobbying for the government to pick of the pockets of smokers.

Which is, of course, what they immediately started doing…