New Last Orders episode out with comedian Leo Kearse. Check it out.

Tuesday, 30 August 2022

Thursday, 25 August 2022

We don't need no stinking evidence!

Having accepted that there is virtually no evidence on which to base population-wide policy, the authors breezily state that it is ‘reasonable to assume that some of the measures used for other public-health concerns could be adapted alongside gambling-specific measures’. Is that a slippery slope you see before you? Why, yes it is.

To find out which policies borrowed from totally different fields might fit the bill, the authors asked 77 experts ‘from our professional networks’. Only 10 of them bothered to reply. They had ‘expertise in alcohol, tobacco, drugs, diet and obesity, and communicable and non-communicable diseases’. But apparently not in gambling.

These 10 people (who remain anonymous) identified no fewer than 103 policy proposals covering a vast range of potential legislation. Some of them are predictable, such as a ban on gambling advertising, a ban on in-play betting and a ban on spread-betting. Some of them are extreme, such as creating a state-owned gambling monopoly and banning the sale of alcohol in casinos. And a lot of them are just weird.

Take, for instance: ‘All gambling products to have plain packaging.’ What does this even mean? What would a plain-packaged fruit machine or roulette wheel look like?

Or: ‘Maximum limit on customers gambling on an operator’s website at once.’ Why?

Or: ‘Tax on wagers proportionate to the risk of harm.’ How do you measure the risk of harm in a wager? Isn’t that just the odds?

Or: ‘Ban all gambling in venues where young or vulnerable people are present.’ How do you define and identify a ‘vulnerable’ person?

And finally: ‘Operators’ duties to rise each year above the rate of inflation.’ Until they all go bust?

It is a bizarre wishlist of half-baked ideas from a group of people who clearly don’t know what they are talking about and have given no thought to whether their ideas can be implemented, let alone whether they would work.

Tuesday, 23 August 2022

A swift half with Alex Deane

New episode of The Swift Half has dropped, this week with conservative commentator Alex Deance. Check it out.

Monday, 22 August 2022

George Monbiot hoist by his own petard

Bill Gates apparently donated $13 million to the Atlantic and the Guardian… in turn, they are churning out articles like this…

— Wall Street Silver (@WallStreetSilv) August 20, 2022

“the most damaging farm products? Organic pasture-fed beef and lamb”…

Paid for activist "journalism". pic.twitter.com/Fwxp1RsIta

Never one to miss out on a retweet, the attention-seeking slaphead James Melville joined in...

Meanwhile, The Guardian has received $12,951,391 in support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. pic.twitter.com/AHwvd5GlFL

— James Melville (@JamesMelville) August 21, 2022

Everything about this conspiracy theory is false. But never mind, let's give it 11,000 likes.

— George Monbiot (@GeorgeMonbiot) August 21, 2022

1. The Guardian asked me to cover a different topic, but I asked to write about this one, as I thought it was more important. In other words, the initiative was entirely mine.🧵 https://t.co/qTt5MbRUA9

6. Like other Guardian journalists, I have been highly critical of Bill Gates, in the Guardian and elsewhere. I see him as a politics denier, purveyor of false solutions and extreme environmental hypocrite. Did he also pay for these opinions? How deep does this conspiracy go???

— George Monbiot (@GeorgeMonbiot) August 21, 2022

8. Please don’t fall for these fables. We're facing real and massive predicaments - the greatest existential crises humanity has ever confronted – and we need to focus relentlessly on what they are and how we avert them. Don’t let the conspiracy theorists mislead you.

— George Monbiot (@GeorgeMonbiot) August 21, 2022

Don't fall for these fables, says the man who describes a think tank that has published the work of twelve Nobel-prize winning economists as "a hoax" and who once gathered a mob to 55 Tufton Street - an address that has become infamous with geographically challenged conspiracy theories - who then vandalised the building.

Monbiot has since argued on Twitter than the Guardian does at least publish the names of its donors, unlike those ghastly free market think tanks, but this isn't true. In the last few years, it has started panhandling for contributions from its readers. You can become a Patron, with packages ranging from £1,200 to £5,000, and you are welcome to give more if you feel like it. Thanks to these donations, the Guardian was able to turn a profit for the first time in 20 years.

The names of these Patrons are kept secret. Rightly so, I would argue. It's no one else's business if I want to give money to a struggling newspaper, just as it is no one else's business if you want to give to a charity like the IEA.

It seems reasonable to assume that the people who become Guardian patrons do so because they broadly support the Guardian's worldview. The reverse explanation - that the Guardian changes its editorial line to match the views of its patrons - is fairly obviously absurd, and yet that is how Monbiot thinks it works in think tanks (not all think tanks, just the ones he doesn't like).

Nevertheless, the hilarious fact remains that Monbiot works for an organisation that is funded by anonymous donors and billionaires. He now finds himself the target of lunatic conspiracy theorists shouting "follow the money" and refusing to believe that anybody in his position can have an opinion of their own.

Oh, what a tangled web we weave!

Zombie businesses

Thanks to inflation hitting double figures last month, average earnings have dropped below the level of 2008 in real terms. A decade of stagnation will soon become a 15-year slump. None of the usual excuses — Brexit, “austerity”, Russia, Covid-19 — adequately explains the economy doing so badly. When economic historians look back on this era, it is the rock-bottom interest rates that will jump off the page. What if they are the cause of our problems, rather than the solution?

The Bank of England began its experiment with ultra-low interest rates 13 years ago and the jury is now in. They manifestly have not stimulated the economy. Instead, they have kept fundamentally insolvent companies afloat, disincentivised saving, propped up the stock market, fuelled a massive housing bubble and encouraged unwise and risky investment.

Do read it if you can.

I was also filling in for Mark Littlewood last month in the same slot, writing about self-funding tax cuts, and will return one more time in a fortnight.

Friday, 19 August 2022

Australian black market for tobacco goes off the scale

|

| 9.5 million cigarettes seized in Freemantle, Western Australia |

A pack of cigarettes costs the equivalent of twenty pounds in Australia these days. It is the most expensive place to smoke in the world. How do smokers afford it?

States join fight against blackmarket cigarettes as border seizures jump 86%Last financial year, the Australian Border Force detected more than 150,000 illegal shipments of tobacco, including more than 1.1 billion illegal cigarettes – an 86 per cent increase on the year before – and 897 tonnes of loose-leaf tobacco (an 8 per cent increase).

“Illicit tobacco works against collective efforts to reduce smoking and tobacco-related harm because it undermines tobacco control measures such as tobacco price increases and plain packaging,” Pearson told the inquiry last year.

“Illicit tobacco also targets the most disadvantaged communities, which already have higher smoking rates, because it is sold significantly more cheaply than regulated tobacco.”

"Once again it is clear that there is no reason to believe tobacco industry propaganda about the relationship between illicit trade, tobacco taxes, plain packaging or other tobacco control measures."

While health groups are lobbying the Albanese government to do more to reduce the smoking rate and respond to the dangers of vaping, Labor has no plan to include another excise increase.

Friday, 12 August 2022

Monkeypox and medical ethics

You are not been alone if you’ve noticed that the public health establishment’s reaction to the monkeypox outbreak has been rather different from its reaction to COVID-19. In the latest episode of Last Orders, Tom Slater drew a parallel with the summer of 2020 when the public health establishment’s attitude towards large gatherings was firmly negative if it involved a loved one’s funeral or a child attending school, but strongly positive if it involved protesting for a fashionable cause.

An article in the current issue of the British Medical Journal criticises the medical response to monkeypox. Written by a New York physician, it highlights several shortcomings which require action: patients are waiting too long to get swabs and vaccines, and suspected cases are told to self-isolate “without being provided a place to isolate, a non-stigmatizing medical reason or note to provide to their employers, or financial protections for work missed.”

Thanks for reading The Snowdon Substack. Subscribe for free to receive new posts.

These problems are relatively easy to solve with some money and effort. I have nothing to add to his recommendations, but my eye was drawn to the conclusion of the article in which he appeals to medical ethics:

And lastly, we must recognize that the least stigmatizing and least homophobic approach to this infectious disease is to provide individuals with information on how it spreads and what steps can mitigate their risk of disease. Our patients have the autonomy to figure out what’s best for them. As a healthcare community, it’s our job to help individuals make informed decisions about what they want to do with their bodies, and provide empathetic care regardless of what that decision is. As doctors, we must show the basic compassion that is missing in all of our policies for monkeypox.

This seems to me to be a reasonable and liberal approach. Indeed, since the author is talking about infectious disease, one might almost describe it as ultra-libertarian. No mandatory vaccines this time around.

Monkeypox is not COVID-19. It is much less deadly and far less transmissible. It is not going to bring any health service to its knees.

And yet it is quite a nasty infectious disease which carries negative externalities, costs money and puts a burden on the healthcare system. If giving people the facts and letting them make their own decisions is the best approach with this contagious disease - and I agree that it is - it would be inconsistent and unethical to demand government coercion against individuals making “informed decisions about what they want to do with their bodies” when those decisions have little or no effect on other people and when the diseases involved are non-communicable.

I am not familiar with the author of the BMJ article. For all I know he could be a prominent campaigner against the nanny state in New York. If so, he has his work cut out. New York’s former mayor, Michael Bloomberg, tried to ban large servings of sugary drinks. Its last mayor, Bill de Blasio, successfully banned the sale of flavoured vapes. It is illegal to smoke in Central Park, a tract of land that is nearly twice the size of Monaco.

I, for one, applaud the author’s call for a humane and liberal approach to risky lifestyle decisions and am heartened to see his views appear in a journal that has not always cherished such principles. I look forward to the public health establishment basing policy recommendations on free choice and individual autonomy in the future.

Our patients have the autonomy to figure out what’s best for them.

Thank you, brother.

Wednesday, 3 August 2022

Minimum pricing isn't working

|

| Promises, promises |

Minimum pricing of alcohol in Scotland is not going well. Self-styled public health advocates are baffled.

.. no changes in the trend direction or statistically significant changes in the level of all alcohol-related crime and disorder

The odds ratio for an alcohol-related emergency department attendance following minimum unit pricing was 1.14 (95% confidence interval 0.90 to 1.44; p = 0.272). In absolute terms, we estimated that minimum unit pricing was associated with 258 more alcohol-related emergency department visits (95% confidence interval –191 to 707) across Scotland than would have been the case had minimum unit pricing not been implemented.

There is no clear evidence that MUP led to an overall reduction in alcohol consumption among people drinking at harmful levels or those with alcohol dependence, although some individuals did report reducing their consumption.

People drinking at harmful levels who struggled to afford the higher prices arising from MUP coped by using, and often intensifying, strategies they were familiar with from previous periods when alcohol was unaffordable for them. These strategies typically included obtaining extra money, while reducing alcohol consumption was a last resort.

MUP led to increased financial strain for a substantial minority of those with alcohol dependence as they obtained extra money via methods including reduced spending on food and utility bills, increased borrowing from family, friends or pawnbrokers, running down savings or other capital, and using foodbanks or other forms of charity.

Some people with alcohol dependence and their family members reported concerns about increased intoxication after they switched to consuming spirits rather than cider. In some of these cases, people also expressed concerns about increased violence.

Alcohol-related hospital admissions refused to decline after the policy was introduced and alcohol-related deaths are at a nine-year high, although lockdowns doubtless had an affect on the latter. The policy cost Scottish drinkers £270 million in its first four years and all the SNP have to cling to is a modest drop in alcohol consumption, much of which is due to COVID-19.

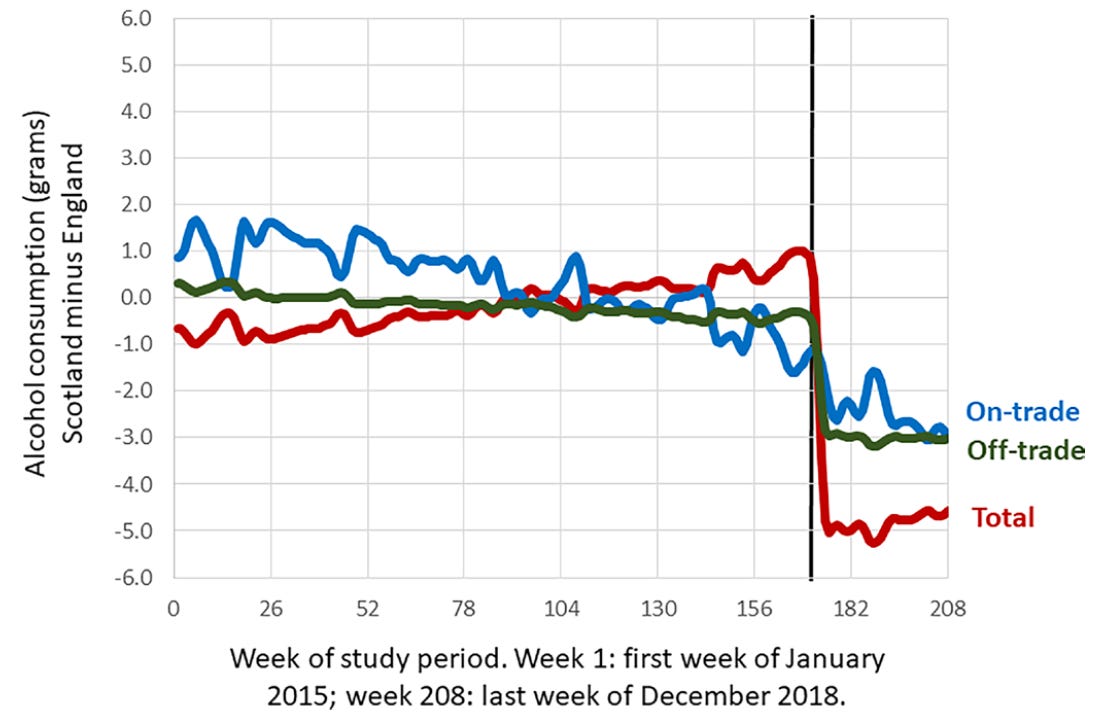

Last month, a new piece of research was published in BMJ Open looking at alcohol consumption. It was not part of the official evaluation and was produced by academics who are very sympathetic to minimum pricing. They nevertheless struggled to make the policy look like a success.

It looks like an impressively steep decline until you realise that 5 grams of alcohol is barely half a unit. Per week. And the reduction in consumption from the off-trade, which is the only place minimum pricing makes any difference, was just 3 grams.

The reductions in consumption are largely driven by women (a reduction of 8.6 g per week, 95% CI 2.9 to 14.3) rather than by men (a reduction of 3.3 g per week, 95% CI –3.6 to 10.4)

For the 95th percentile the introduction of MUP was associated with an increase in consumption for men of 13.8 g (95% CI 5.8 to 21.5), but not for women (4.8 g, 95% CI −4.0 to 13.7).

For younger men there was an increase in off-trade consumption, which was offset by decreases in on-trade consumption in the same group.

None of these findings are terribly surprising to people who are more worldly than your average ‘public health’ academic. Raising the price of cheap booze was always more likely to change the behaviour of moderate tipplers than heavy drinkers. Hardcore drinkers were always going to find money to keep drinking and minimum pricing was never going to help the pub trade. It was only likely to make the poor poorer.

When the Minister for Public Health, Sport and Wellbeing introduced the 2018 alcohol policy framework, he emphasised that the implementation of the MUP [minimum unit price] was strongly motivated by an interest in decreasing health inequalities through a reduction in alcohol consumption among the heaviest and most vulnerable drinkers. Our results indicate that this goal may not be fully realised…

… first, we found that women, who are less heavy drinkers in our data and in almost all surveys worldwide to date, reduced their consumption more than men; second, the 5% of heaviest drinking men had an increase in consumption associated with MUP; and, third, younger men and men living in more deprived areas had no decrease in consumption associated with MUP. These results are surprising as modelling studies would have suggested otherwise.

We do not know why, for both younger men (those aged <32 years) and for those living in residential areas in the bottom two-fifths of deprivation, there was no decrease in consumption associated with MUP compared with older men and those living in less deprived areas.

Several studies have found that overall, heavier drinkers— including people with alcohol use disorders—react less to price than the general population (ie, they react more price inelastic and their consumption is determined by other factors). However, while this may explain lower reductions, it cannot explain an increase in consumption.

The results may also imply a diminished impact on alcohol-attributable hospitalisations and mortality, which have been shown to be strongly associated with heavy drinking in men and in those of lower socioeconomic status. Indeed, a large controlled study on emergency department visits following the introduction of MUP did not show any reduction in alcohol-related emergency department visits.

In a sensational act of hubris, three activist-academics published an article in 2017 claiming that the evidence-base for minimum pricing, a policy that had never been tried anywhere, fulfilled the great epidemiologist Austin Bradford Hill’s criteria for causality. It seemed absurd at the time and it seems almost grotesque now.

If indeed the findings of our study are corroborated, then additional and/or different pricing mechanisms may need to be considered to reduce alcohol-attributable hospitalisations and mortality.

‘Tis but a flesh wound!

Postscript

Following the introduction of MUP, total household food expenditure in Scotland declined by 1.0%, 95%CI [-1.9%, − 0.0%], and total food volume declined by 0.8%, 95%CI [-1.7%, 0.2%] compared to the north of England.

There is variation in response between product categories, with less spending on fruit and vegetables and increased spending on crisps and snacks.

Tuesday, 2 August 2022

The fantasy world of public health modellers

Remember the study claiming that the Transport for London ban on 'junk food' advertising had let to London households consuming 1,000 fewer calories per week? It was execrable rubbish and now a study based on it is claiming that nearly 100,000 cases of obesity have been prevented by the ban.

Regardless of what you think of this particular policy, it is worrying that public health policy-making has become so divorced from observable reality. Policies are proposed on the basis of modelling, evaluated on the basis of modelling, and the modelling is carried out by advocates of the policy. At no point are facts allowed to intrude. A rise in chocolate consumption becomes a fall in chocolate consumption. A rise in obesity becomes a fall in obesity. Activist-academics have created a world of pure imagination and are exploiting the broken peer-review process to drag us all into their land of make believe.

Monday, 1 August 2022

Nicotine use, past and present

So, here is the interesting question. What if nicotine use is no longer all that harmful? What if the real problem was always the inhalation of toxic smoke while trying to consume nicotine for its benefits? As early as 1991, the leading medical journal The Lancet reflected on how the nicotine landscape might look after the year 2000: “There is no compelling objection to the recreational and even addictive use of nicotine provided it is not shown to be physically, psychologically or socially harmful to the user or to others.”

In my view, we have reached the position where smoke-free nicotine products, such as e-cigarettes, heated tobacco, smokeless tobacco or nicotine pouches, can provide nicotine at acceptably low risk. By acceptably low risk, I don’t mean perfect safety, but within society’s normal risk appetites for consumption and other recreational activities. If continuing innovation in the design of the products ultimately leads to smoking cigarettes becoming obsolete, then the vast burden of smoking-related disease will decline and fade away.

E-cigarette facts and evidence

There is conclusive evidence that the use of e-cigarettes can cause respiratory disease

(Based on the EVALI outbreak which had nothing to do with e-cigarettes.)

And...

There is strong evidence that never smokers who use e-cigarettes are on average around three times as likely than those who do not use e-cigarettes to initiate cigarette smoking.

(A claim that ignores the large decline in smoking rates among young people since vaping went mainstream and ignores common liability.)

Contrary to the conclusions of the Banks review, the evidence suggests that vaping nicotine is an effective smoking cessation aid; that vaping is substantially less harmful than smoking tobacco; that vaping is diverting young people away from smoking; and that vaping by smokers is likely to have a major net public health benefit if widely available to adult Australian smokers.

Congratulations Professor Emily Banks AM FAHMS, recipient of the prestigious @ama_media Gold Medal for her outstanding service to medicine, including ground-breaking research establishing evidence of the significant harms of e-cigarettes.@ANUPopHealthhttps://t.co/gY0uWnU8Wo

— AAHMS (@AAHMS_health) July 31, 2022