Professor David Nutt is a curious fellow. He is quite sound on vaping

and drugs, but horribly puritanical about alcohol. The problem lies in

his blinkered view of psychoactive substances which focuses solely on

‘harm’ and ignores both the benefits of taking the substance and the

societal context in which consumption takes place.

For

Nutt, ‘harm’ generally means the damage to the health of the user and

those around him, but he will sometimes include barely measurable harms

such as ‘loss of relationships’, ‘family adversities’ and ‘community’ to

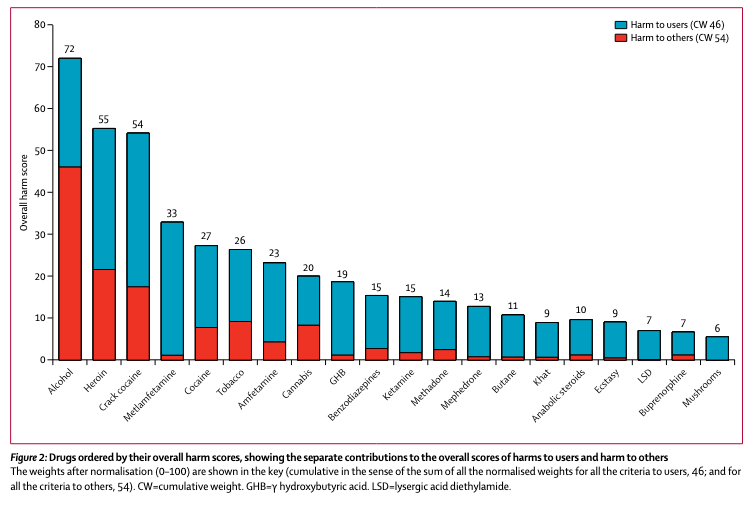

bulk up the figures. By this dubious method, he once produced a league table of substances

in which ketamine, GHB and benzodiazapine were portrayed as better than

alcohol. In fact, everything in the league table was better than

alcohol, even tobacco.

From

this, Nutt concluded that ‘the present drug classification systems have

little relation to the evidence of harm’. The implication was that

either alcohol should be banned or everything should be legal.

Now,

it might be true in some sense that ketamine is a safer drug than

alcohol, but it would hardly be an appropriate substitute for alcohol at

a wedding, for instance. It isn’t even much of a substitute for alcohol

in a pub.

While

I agree with Nutt that MDMA and cannabis should be legal, I have long

had concerns over his research, much of which seems to be blatantly

agenda-driven and sloppy. His articles about alcohol, in particular, are

riddled with errors. He is happy to repeat any old canard from the

temperance lobby so long as it paints booze in a bad light. I have

written about this again and again and again.

In January 2020, he published a book called Drink?: The New Science of Alcohol and Your Health. I haven’t read it and have no urge to do so, but I could see from his summary of it in the Daily Mail that it was packed full of half-truths, lies and exaggerations.

I had forgotten all about it until I read this post by Fergus McCullough

who is very impressed by the book. The parts he quotes irritated me

because they are largely untrue, but it irritates me even more to think

that somebody believed them. This is not Fergus’s fault, as such. People

should able to believe a book written by a professor. Nevertheless,

what Nutt says is frequently wrong.

Take the health

benefits of moderate drinking, for example, which seem to rile the

anti-alcohol lobby more than anything. Fergus writes:

What

I didn’t realise before, though, is how poorly evidenced the beneficial

effects of alcohol are. Looking at the available studies, Nutt writes

that the positive effect on cardiovascular health has never been

definitely proven (i.e. beyond mere association), and even if there is a

small positive effect, the optimal level of consumption would be around

one unit a day. The benefits don’t outweigh all the other risks.

Never

definitely proven ‘beyond mere association’? OK, so we don’t trust

observational epidemiology. But two paragraphs earlier, Fergus quotes

the following from Nutt’s book:

Alcohol use is one

of the top five causes of disease and disability in almost all

countries in Europe. In the UK, alcohol is now the leading cause of

death in men between the ages of 16 and 54 years, accounting for over 20

per cent of the total. More than three quarters of liver cirrhosis

deaths, 7 per cent of cancer deaths and 25 per cent of injury deaths in

adults under 65 years of age in Europe in 2004 were estimated to be due

to alcohol.

How do we know that alcohol

causes these diseases and injuries? From ‘mere association’ in

epidemiological studies - the same kind of epidemiological studies that

have consistently shown lower rates of cardiovascular disease and lower overall mortality among moderate drinkers for decades. Later in his post, Fergus says (presumably quoting Nutt):

Treating the results of excessive alcohol consumption is a huge burden for the NHS. In England alone, around 350,000 hospital admissions per year are mainly attributable to alcohol.1

Nobody

is counting these people in hospitals. The 350,000 is an estimate based

on attributable fractions which simply assume that a certain proportion

of hospital admissions for a given ailment is caused by alcohol. So,

for example, if two people die from drowning, one of them is assumed to

be an alcohol-related death. All of this is ultimately derived from the

‘mere associations’ of observational epidemiology. (Last year, the

Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (neé Public Health

England) changed the methodology and the number of ‘alcohol-related’ hospital admissions dropped massively.) There

is no ‘definite proof’ that alcohol causes cancer. There is no

‘definite proof’ that smoking causes cancer, for that matter. It is

practically imposssible (and unethical) to conduct randomised controlled

trials to prove it either way. What we have instead is a wealth of

observational evidence backed up with a plausible biological mechanism

and no other reasonable explanation for the statistical associations.

And that is what we have to show that moderate drinking is good for the

heart and helps people live longer.

In fact, the evidence of

health benefits from moderate drinking is stronger than the evidence for

alcohol causing any form of cancer. There are more studies from more

countries over a longer period of time and the hypothesis has been

tested more rigorously precisely because people like Nutt don’t want to

believe it.

I am on two mailing lists for alcohol research

and barely a week goes by without a new study showing health benefits

from moderate alcohol consumption. Occasionally I will tweet them,

but generally I ignore them. For anyone familiar with the field, it is a

non-story. The evidence is so overwhelming that it takes a huge amount

of motivated reasoning to ignore it. The response from the likes of Nutt

is exactly the same as the tobacco industry’s response to the evidence

on smoking and lung cancer in the 1950s. They dismissed it as a mere

statistical association and demanded an impossible burden of proof.

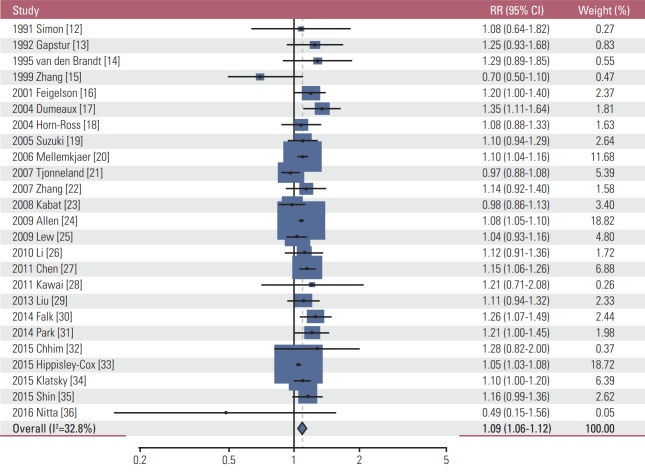

I have written plenty about the alcohol J-Curve elsewhere so won’t go over it again, but to give you an idea of the double standard at work, here are the results from a meta-analysis of light alcohol consumption and breast cancer risk, which Nutt believes to be conclusive.

Only

a handful of the studies produced statistically significant results and

the combined relative risk was a tiny 1.09 (1.06-1.12).

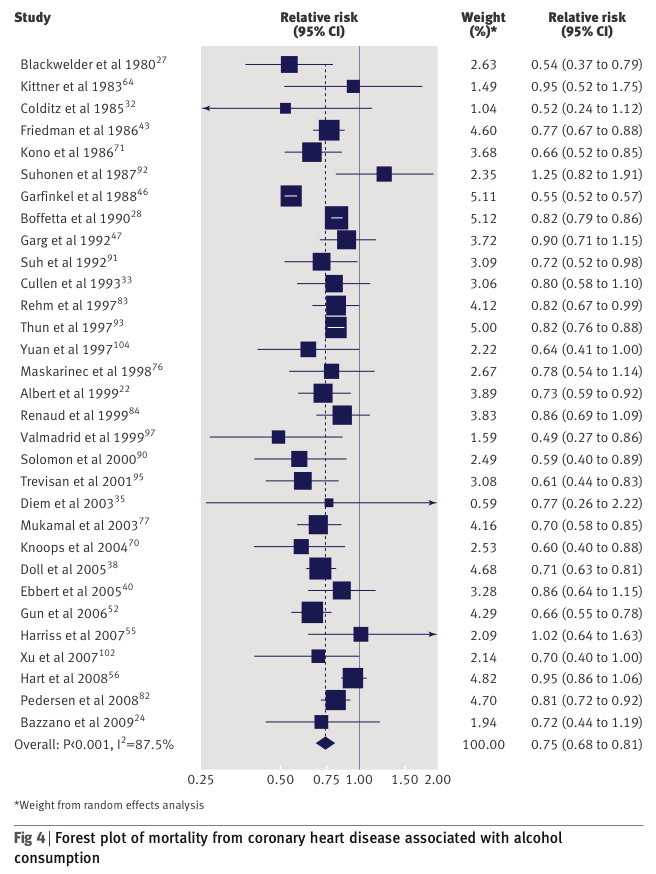

And here are the results from a meta-analysis of moderate drinking and coronary heart disease which Nutt thinks ‘has never been definitely proven’.

Here,

most of the studies are statistically significant and the effect is

larger. A relative risk is 0.75 (0.68 to 0.81) means the moderate

drinkers are 25% less likely to die from a very common disease. If

moderate drinking was a drug, they’d be prescribing it.

Incidentally, the authors of the first study found a statistically significant reduction in lung cancer risk among the light drinkers, a result that I suspect Nutt would not take seriously (and I wouldn’t blame him).

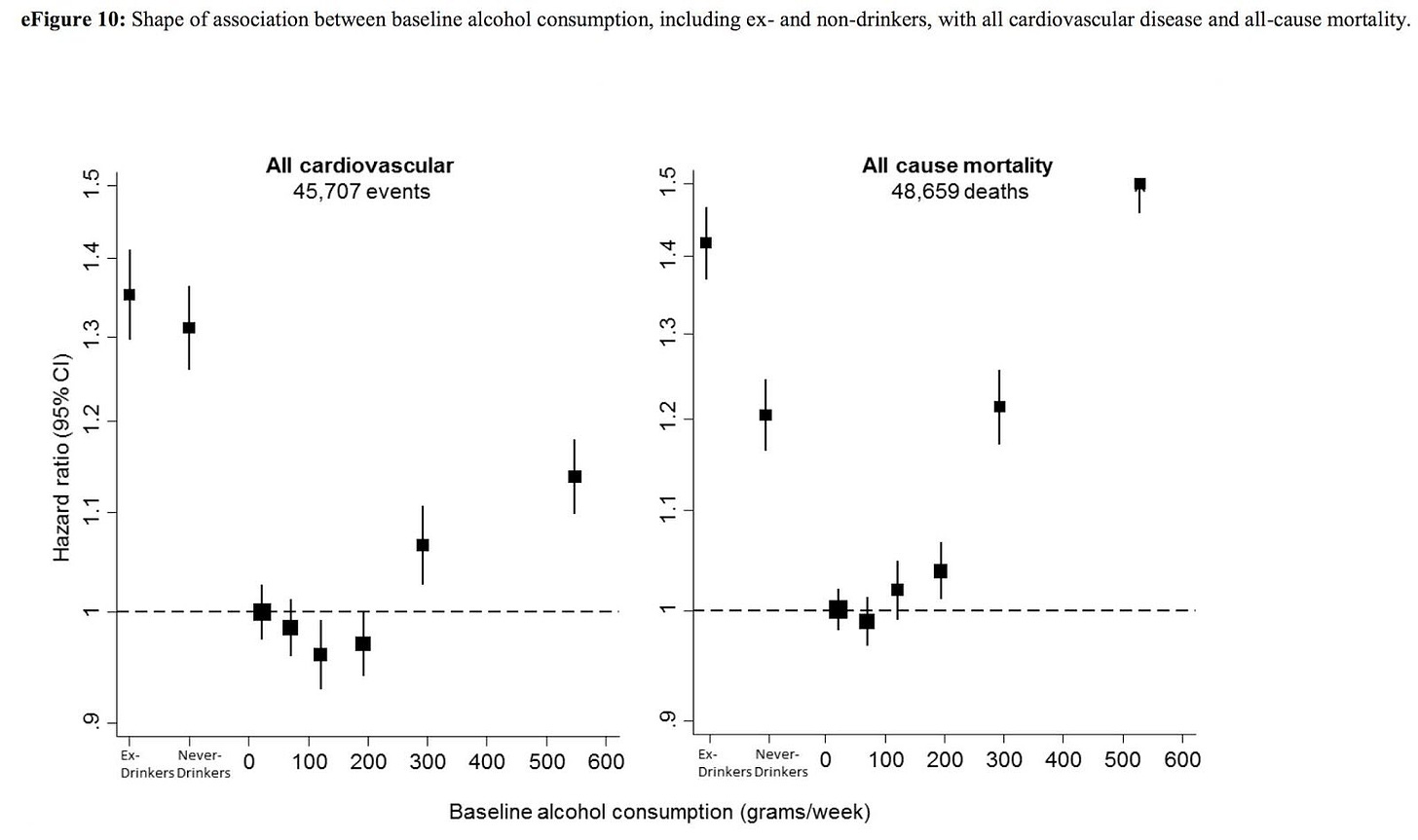

As for the claim that ‘The benefits don’t outweigh all the other risks’, here is what overall mortality looks

like. The teetotallers have a 20% increased risk of premature death

compared to moderate drinkers. Note also how these graphs refute the

tired old cope from the ‘sceptics’ that teetotallers only die younger

because many of them are sickly former alcoholics. These graphs separate

never-drinkers, ex-drinkers and current drinkers.

We then move on to economics. Nutt writes:

…it’s

been estimated that when you add in the costs of alcohol to society,

there is a net loss to the Exchequer. This is undeniably a difficult

argument to disentangle economically, and a complicated sum. But the

costs of alcohol to society are relatively well established. These are:

£3.5bn on health, especially hospital admissions and accident and

emergency attendances; £6.5bn for policing drunkenness; £20bn for lost

productivity through hangovers. The total is £30 billion.

So

two-thirds of the ‘cost to society’ consist of lost productivity as a

result of hangovers? As health economists tire of having to point out,

lost productivity is not an external cost. If you are less productive,

you get paid less and get passed over for promotion. The cost falls on

you. It is not a cost to society and certainly not a cost to ‘the

Exchequer’.

In any case, drinkers seem to be more productive than teetotallers and get paid more, probably because they increase social capital and have larger social networks.

As for the more relevant costs to government, some of these are real but when I looked at them in 2015 they amounted to £3.9 billion, which is barely a third of what the government gets from alcohol duty.

Fergus says:

It’s strange that this isn’t talked about more. Polls suggest

that the NHS is the one institution that almost everyone in Britain

cares about. So why not ease the burden on its workers – and the public

purse – by reducing our alcohol consumption?

Personally,

I don’t care about the NHS. In fact, I despise it. And there are good

reasons why we don’t we ‘ease the burden on its workers’ by reducing our

alcohol consumption. It’s because alcohol duty comfortably pays for

alcohol-related healthcare costs and because the NHS is there to look

after us, not the other way round.

Nutt seems to think that people in the UK are exceptionally heavy drinkers and Fergus has taken this on board, saying:

Notably, that there are enormous differences in the levels of alcohol consumption around the world.

Some of this is because of religious prohibitions on alcohol in

Muslim-majority countries, or because many people carry genes that mean

they feel flushed and nauseous after consuming alcohol

(commonly known as Asian flush). But even among countries with no

religious or biological hindrances to alcohol, consumption varies a lot,

and Britain and Ireland do unusually poorly on this front.

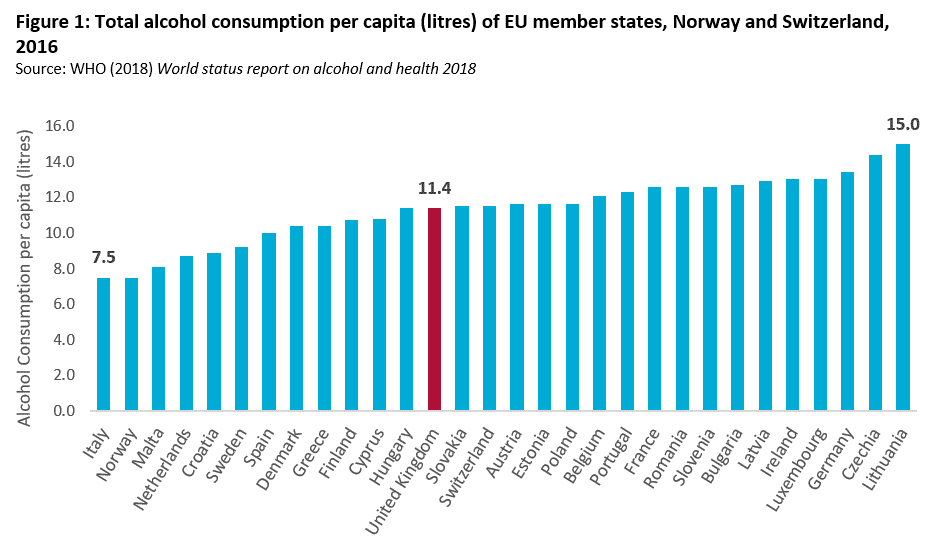

Doing

poorly means drinking a lot, as far as Fergus is concerned. But we

don’t actually drink particularly heavily in the UK, as the chart below

shows. Consumption in Ireland is higher but has fallen a lot in recent years.

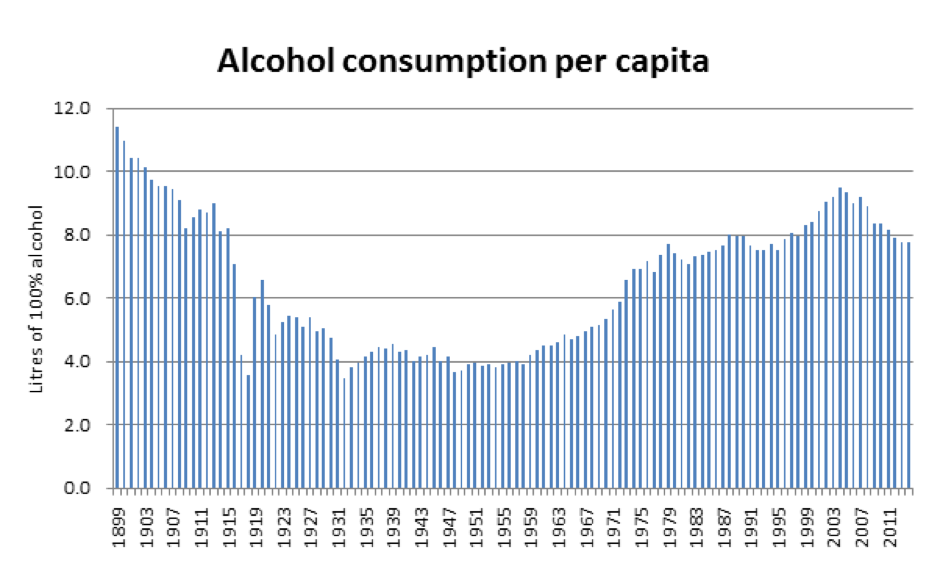

One might assume that the British (and Irish) have always been habitual drunks. In fact, there has been significant variation

in the amount of alcohol British people have consumed over the past few

centuries. We’re at (or just after) the peak of a decades-long trend of

more alcohol being consumed in Britain.

We’re

definitely after the peak, which was in 2004, and we’re now back to the

levels of the 1980s. The world wars clobbered alcohol consumption and

the last decades of the 20th century saw drinking climb back to pre-WWI

levels, although it has never returned to Edwardian levels.

Still, what is to be done? Quite a bit, according to Nutt.

Nutt

suggests his own set of policy solutions: taxing drinks by the amount

of alcohol in them and increase that tax back to 1950s levels (i.e.

triple it); stop selling strong alcohol in supermarkets; make it a law

that all alcohol outlets must sell non-alcoholic drinks; install

breathalysers in pubs and stop drunk people from buying more alcohol;

banning all alcohol advertising; and many more.

Yikes! I much prefer his work on Ecstasy, to be honest.

He

focuses most on minimum unit pricing (MUP), i.e. a floor on the price

at which a unit of alcohol can be sold. As the government has not raised

its duty on alcohol, it now costs a third of what it did in 1970 in real terms.

It does not cost less in real terms. It costs more

in real terms. The price of alcohol has gone up by more than the cost

of a basket of goods, i.e. above the general rate of inflation. It has

come down in relation to average incomes which means that it is more affordable

- making things more affordable is the whole point of raising incomes -

but the price has not fallen in real terms. This is a common

misunderstanding.

As for minimum pricing, the jury was

still out when Nutt was writing his book in 2019, but his high hopes for

the policy have not aged well.

Scotland introduced MUP in 2018 – with initially positive results:

…the

amount of alcohol bought in shops and supermarkets per person per week

fell by 1.2 units (just over half a pint of beer or a measure of

spirits) compared with what would have been drunk without MUP. In

England over the same time, consumption increased. The biggest drop –

two units a week – was in the heaviest fifth of drinkers.

Targeting

the heaviest drinkers is important because they are the worst affected;

they account for the vast majority of the health costs.

Alas,

the heaviest drinkers did not play ball and the modest reduction in

alcohol consumption did not yield any health benefits. As I discussed in

a recent post, minimum pricing has backfired horribly. The official evaluation concluded that…

There

is no clear evidence that MUP led to an overall reduction in alcohol

consumption among people drinking at harmful levels or those with

alcohol dependence, although some individuals did report reducing their

consumption.

People drinking at harmful levels who struggled to

afford the higher prices arising from MUP coped by using, and often

intensifying, strategies they were familiar with from previous periods

when alcohol was unaffordable for them. These strategies typically

included obtaining extra money, while reducing alcohol consumption was a

last resort.

And a recent study found that among the heaviest drinking men, consumption actually increased…

For

the 95th percentile the introduction of MUP was associated with an

increase in consumption for men of 13.8 g (95% CI 5.8 to 21.5), but not

for women (4.8 g, 95% CI −4.0 to 13.7).

Nevertheless, Fergus is so impressed with this book that he thinks Nutt should go even further.

The

evidence here is so damning that I wonder how Nutt can still suggest,

in good conscience, that we should still drink (within limits). Some of

the arguments he makes in favour of alcohol are ridiculous:

A glass to hold gives us something to do with our hands in awkward situations, particularly now smoking has become so vilified.

I

agree that is ridiculous. The only justification people need to drink

is that they enjoy it. Same with vaping. Same with cannabis. Same with

ecstasy. So long as you pay your way and don’t hurt anyone, do what you

like.

Alcohol. Where would we be without it? Qatar.

And then comes the big reveal…

I don’t enjoy drinking alcohol, frankly.

Knock me down with a feather!

I

drink a little bit on some social occasions, but, following my

arguments here, I’m not sure that I should. Abstention from alcohol is

more or less costly for different individuals, and I am one of those

fortunate enough to manage it with ease.

Whatever works for you.

It’s

possible to consume alcohol in a safe manner, with risks to your

long-term health that you might consider acceptable, if you enjoy

drinking it. But, if you do so, then, at the margin, you are contributing to the idea that it’s normal to drink it.

It is normal to drink it. 83% of adults drink alcohol in Britain and we’re not going to stop just to make you feel less weird.

And that norm should be broken down. Drinking alcohol should always be a choice, not a default.

What

does this even mean? When is drinking alcohol the default? In a pub, I

suppose, but even there you still have a choice. If you really don’t

like drinking, pubs might not be the best place for you, especially if

you’re going to spend the whole time citing dodgy factoids and demanding

neo-prohibitionist legislation.

I don’t mind people not drinking, I just wish they wouldn’t do it around me.

First published on the Snowdon Substack.