In the

Guardian, Sarah Boseley has written a useful article about obesity. Useful because it brings a whole bunch of obesity myths together in one place. Let's take her "10 shocking facts" in turn...

1. Nearly two-thirds of the UK population is either overweight or obese

This is true and, to Boseley's credit, she doesn't adopt the sneaky tactic of merging the overweight and obese together as if they were all obese.

The overweight live longer than those of 'normal weight' so the obese are the only ones we are interested in from a 'public health perspective'. She doesn't tell us how many are obese (24%), nor does she mention that this number has barely risen for a decade. But she does add this little nugget...

There is a community effect: you are more likely to be overweight if your friends and neighbours are and you see it as the norm.

This is a reference to the

Christakis and Fowler study which invented the concept of 'passive obesity'. The study has been

comprehensively debunked. It contains errors that are

"so egregious that a critique of their work cannot exist without also calling into question the rigor of review process."

2. Obesity is shortening our lives

Moderate obesity (BMI 30-35) cuts life expectancy by two to four years and severe obesity (BMI 40-45) by an entire decade, according to a major study in the Lancet in 2009. This is most likely to affect today's children; more than a fifth of five-year-olds and a third of 11-year-olds are overweight or obese. "Obesity is such that this generation of children could be the first in the history of the United States to live less healthful and shorter lives than their parents," said Dr David S Ludwig, director of the obesity programme at the Children's Hospital Boston

Obesity is certainly a risk factor for diseases that can and do shorten lives. Whether it is actually 'shortening our lives' in absolute terms while life expectancy continues to rise is much more debatable. It is more than likely that life expectancy will rise by more than the 'two to four years' mentioned above by the time today's children reach late middle age and it is almost certainly untrue that these children will live shorter lives than their parents.

As I have mentioned before, life expectancy figures keep on rising and the number of babies who are thought to live to the age of 100 continues to go up.

3. Obesity could bankrupt the NHS

The NHS spends £5bn a year on diseases such as strokes and diabetes that are linked to obesity. Within a few decades, that is predicted to climb to £15bn. Type 2 diabetes is a huge problem: 10% of the NHS budget already goes on that alone.

Diabetes is certainly on the rise (

though not as much as predicted) and it is certainly obesity-related. Diabetes and its complications can be expensive to treat and it is probably the most concerning aspect of the rise in obesity. But bankrupt the NHS? What does that even mean? Are we going to turn up at A & E one day and find the shutters down and the staff laid off?

No. The government will just tax more and borrow more. The government is borrowing the best part of £100 billion a year already. Scandalously, it spends nearly £50 billion just paying off the interest on the debt. I don't support this and it's clearly unsustainable, but where are all the public health people demanding urgent cuts to stop the country bankrupting itself? There are nowhere to be seen; indeed, they are fiercely against [cough] 'austerity'.

The only time the public health racket ever expresses an interest in fiscal discipline is when they can blame smokers, drinkers and fatties for being a 'drain on the NHS'. Which is nonsense anyway because

the healthcare costs of the obese are lower than those of the 'normal weight'.

4. It's an unfair fight

The government spends £14m a year on its anti-obesity social marketing programme Change4Life. The food industry spends more than £1bn a year on marketing in the UK.

Because people wouldn't eat food if it wasn't for marketing, right?

This is such a weak and tedious argument. Firstly, advertising can't make someone buy a product they don't want. Secondly, a large proportion of the £1bn marketing budget is for 'healthy' food. Thirdly, lots of heavily consumed 'unhealthy food' has little or no advertising behind it (chips, pies, pasties, kebabs etc.). Fourthly, the rise in obesity is

primarily due to physical inactivity, not increased calorie consumption (the latter has fallen). Fifthly, if you think that people would behave in a significantly different way if the 'anti-obesity social marketing programme' had a billion pounds to spend, you don't understand people.

It's not just the in-your-face bright packaging with happy slogans, but which aisle the product is in. Food companies pay a premium to have their merchandise on end-displays, which account for 30% of supermarket sales. We are not as in control of our shopping as we like to believe. We go in with good intentions – we come out with large bottles of fizzy drinks and packets of biscuits.

In virtually every supermarket I've ever been in, the fruit and vegetables are the first thing you see when you walk in. It doesn't tempt me to buy either. And, by the way, why is it only the manufacturers of 'unhealthy' food that have cottoned on to the power of advertising and promotion in GuardianWorld? Could it be that advertising follows demand and not vice versa?

5. Obesity took off in the have-it-all 80s

But it was unregistered by the government in power. McDonald's moved its headquarters into Margaret Thatcher's Finchley constituency in 1982, three years after she became prime minister. She opened the building in 1983 and visited again in 1989, on the 10th anniversary of her prime ministership, when she congratulated the company on the jobs it had created and its economic success.

I have quoted this section in full in the hope that a reader might be able to tell me what the hell it is supposed to mean. It seems to be a vaguely conspiratorial piece of

Guardian anti-Thatcherism thrown in for the sake of it, but perhaps I'm missing something. Oh, and by the way,

kids who eat at McDonald's are slimmer than those who don't.

6. Snacking is "a newly created behaviour"

It was virtually unknown before the second world war, according to Barry Popkin, professor of nutrition at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Public Health.

I don't know what research this refers to (although I do know that

Popkin is a rum fellow). It seems rather implausible that snacking is a post-war invention.

Crisps were invented in the nineteenth century. The Rowntree and Cadbury chocolate dynasties were also founded in the nineteenth century. Cakes, biscuits and pastries have been around even longer. Presumably somebody was eating these snacks at the time. I do, however, agree that if you want to lose weight, cutting out snacks is one of the best ways to do it.

7. The food industry is behaving as the tobacco industry did

Big Food is the new Big Tobacco. Yawn.

Large numbers of scientists advise the food industry and take funding for research because they are focused on the micro, not the macro picture. The "sustaining members" of the British Nutrition Foundation include Coca- Cola, Kellogg's, Mondelez (owner of Cadbury), Nestlé, PepsiCo, Tate & Lyle, Associated British Foods and Unilever. The chair of the government's nutritional advisory committee investigating carbohydrates, including sugar, is Professor Ian Macdonald from Nottingham University, who has been an adviser to Coca-Cola and Mars.

I would be very concerned if the food industry

didn't employ scientists. I hope and expect that they are of a higher calibre than the fringe cranks that are involved with Action on Sugar. But what matters is the quality and veracity of their research—a question that Boseley sidesteps.

8. Your brain, not your stomach, tells you when to stop eating

Hunger is in the mind. Dr Suzanne Higgs at Birmingham University carried out a remarkable experiment to prove it. Her team gave a group of amnesiacs a lunch of sandwiches and cakes. When everybody had finished eating, they cleared away and brought in a fresh lunch 10 minutes later. A control group of people with no memory problems groaned and refused any more food. The amnesiac group tucked in and ate the same again.

Cool story, bro.

9. By the age of five, it is almost too late to intervene

The EarlyBird diabetes study of 300 children in Devon showed that they had already gained 70–90% of their excess weight before primary school. It is far harder to get rid of weight than to put it on, even as a child. Some experts think that if we want to prevent obesity, we're going to have to find ways to help parents from, or even before, the birth of their baby.

What does '

almost too late to intervene' mean? Is it too late or isn't it? Let me answer that—it's not too late. If you burn more calories than you consume, you will lose weight. It is obvious that it is 'harder to get rid of weight than to put it on' because putting it on weight requires no thought or effort whatsoever. The question is whether it is possible to lose weight after the age of five, to which the answer is clearly 'yes'.

We think obesity is about adults eating fried chicken and chips.

Do we? I don't. Or does the 'we' refer to

Guardian readers who have told for years that it's those ghastly American fast food chains that have created the obesity 'epidemic'?

Those who think children are getting fat because they sit in front of the television too much may also be wrong. Another finding from EarlyBird was that inactivity does not lead to obesity – obesity leads to inactivity.

Yeah, let your kids sit around watching television all day, they won't get fat. You know it's true because you read it in the

Guardian. This is exactly the sort of irresponsible rubbish

I wrote about a couple of days ago.

Of course fat people do less exercise than slim people, but it is dangerous, scientifically illiterate nonsense to claim that 'inactivity does not lead to obesity'.

10. Obese children are increasingly being taken into care

At least 74 in the past five years, according to a Freedom of Information request from the Daily Mirror

It is probably true that numbers are increasing (although Boseley presents no evidence for it), but we are talking about

very small numbers in a country of 65 million people. There will always be extreme cases at the far end of the bell curve. Each case is unfortunate and the causes are likely to be complex (including a genetic element in some instances), but a handful of freakishly fat children does not tell you a great deal about the overall trend.

Rates of childhood obesity peaked ten years ago and have been falling ever since.

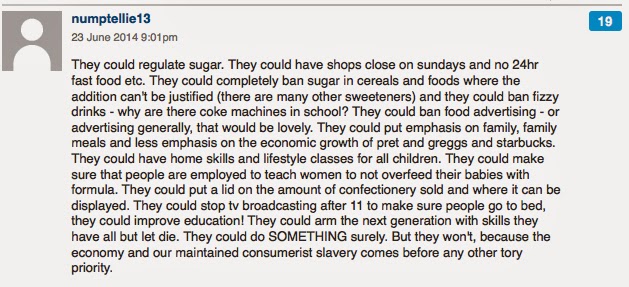

And that's it. The article has produced some classic comments from 'liberals'.