Carl Phillips and Marewa Glover have produced

a very interesting study assessing the efficacy of anti-smoking policies in the USA. With the exception of tax rises, they find very little evidence that any of them have made any measurable difference to smoking rates and that most, if not all, in the fall in smoking rates would have happened without any legislation.

Why, then, have smoking rates been declining for decades? Their theory is

that it began with the "information shock" of public health authorities,

such as the Surgeon General, declaring smoking to be a major health

risk in the 1960s. This led to an immediate decline in smoking rates

which has echoed down the years through inter-generational effects. As

they note, the most robust predictor of individual smoking initiation is

parental smoking. When parents quit or never start smoking, their

offspring are less likely to smoke.

And so, by their calculations...

Results: About one-third of the observed prevalence decline through 2010 can be attributed solely to fewer parents smoking after the initial education shock. Combining peer-group cessation contagion explains well over one-half of the total historical prevalence reduction. Plausible additional echo effects could explain the entire historical reduction in smoking prevalence.

Conclusions: Ongoing anti-smoking interventions are credited with ongoing reductions in smoking, but most, or perhaps all that credit really belongs to the initial education and its continuing echoes. Ensuring that people understand the health risks of smoking causes large and ongoing reductions. The effect of all other interventions (other than introducing appealing substitutes) is clearly modest, and quite possibly, approximately zero, after accounting for the echo effects.

I recommend reading the whole study, but the following section should give you the gist of what they mean by echo effects:

We know that choosing to smoke is socially contagious – the more people around someone who smokes, particularly their parents, the more likely they are to start smoking.1 Parental smoking is the most consistent strong predictor of whether a teenager (of a particular age, in a particular population) will start smoking. Smoking prevalence among siblings, peer groups, and the wider community affects uptake via overt and subconscious social signaling. All of these are taken as fact in the scientific literature and in

Phillips et al

tobacco control politics, where they are cited as motivation or points of leverage for interventions. But one important implication – that a downward shock or trend in smoking prevalence will, by itself, cause further downward trending for more than a generation – is generally ignored.

Similarly, smoking cessation is a contagious behavior. This is particularly clear for switching to a lower-risk alternative, wherein the person quitting smoking demonstrates to their social contacts that the choice is appealing and educates them about the alternative. However, even if the choice of cessation method is not affected by social-contact education, the demonstration effect of quitting itself is still powerful. Seeing a friend quit smoking takes it from being an abstract possibility to a concrete example of success. In addition, simply having fewer people who smoke in one’s social circles encourages quitting. Each of these, and all of them together, creates a positive feed-forward effect from any smoking reduction.

Thus, a one-time permanent downward shock in the popularity of smoking – like that caused by initial education about the harms from smoking – causes a long tail of transition to a new lower equilibrium, echoes of the initial shock. If many people quit smoking, then many more who would have started smoking had they come of age earlier will not do so and others will be motivated to quit over time. The subsequent cohorts coming of age not only will experience the effect of the downward shock, but also be subject to less social contagion. There will be a new equilibrium, but it will only be reached slowly, with a substantial portion of the effect taking more than a generation. This will happen with or without any further efforts to discourage smoking. Subsequent interventions could still have effects beyond the secular trend toward a new equilibrium, of course, but it makes no sense to try to quantify those effects without trying to estimate the background effects of the echoes alone.

Phillips and Glover stress that it cannot be proved either way whether the bulk of anti-smoking regulation has made a difference to smoking rates. They present a hypothesis and a series of models. But it is an intriguing hypothesis and I have often wondered to what extent the tobacco control lobby has been dining out on a decline in smoking rates that would have happened without them (and for many years did happen without them).

That would certainly help explain why tobacco-style regulation fails to work when applied to other activities. These policies tend to focus on the Three As - affordability, advertising and availability - but whilst it is Econ 101 to note that higher prices tend to lead to lower consumption, albeit at the expense of consumers, the evidence for the other two As is remarkably thin on the ground.

Take alcohol. A 2019 systematic review titled 'Do alcohol control policies work?' and written by two members of the South African Medical Research Council concluded that ‘[r]obust and well-reported research synthesis is

deficient in the alcohol control field despite the availability of clear

methodological guidance.’ The policies examined included restricting alcohol advertising and restricting on- and off-premise outlet density.

With regards to advertising, a Cochrane Review,

which is usually considered definitive, found 'a lack of robust

evidence for or against recommending the implementation of alcohol

advertising restrictions'.

Even the authors of Alcohol: No Ordinary Commodity, the bible of the secular temperance movement, were only able to make a limp case for advertising bans.

‘Imposing total or partial bans on advertising produce, at best, small effects in the short term on overall consumption in a population, in part because producers and sellers can simply transfer their promotional spending into allowed marketing approaches. The more comprehensive restrictions on exposure (e.g. in France) have not been evaluated… The extent to which effective restrictions would reduce consumption and related harm in younger age groups remains an open question.’

A systematic review published in 2012 tried very hard to find evidence to support orthodox, supply-side anti-alcohol policies. It was written by dyed-in-the-wool 'public health' activists, including Mark Petticrew and Martin McKee, but they really struggled to find what they wanted.

On advertising, they found seven studies which 'provided inconclusive results for the influence of

advertising on alcohol use'.

There wasn't much evidence and a lot of it was of poor quality, but...

A study rated as ‘strong’ in the quality assessment found no

significant association between exterior advertising in areas near

schools and adolescent drinking.

The authors nevertheless concluded that...

In general, the findings of this review are consistent with reviews on

wider alcohol availability (Popova et al., 2009), which have found that

availability has a strong influence on alcohol use.

But this is mere editorialising. The evidence they discuss in the paper doesn't show that at all.

In general, the results of this review are similar to those found in

previous reviews (Babor et al., 2003)—studies show mixed results but

strongly indicate that greater exposure to advertising is associated

with higher levels of alcohol use.

How can mixed results strongly show anything?

They also looked at availability - including licensing hours and outlet density - and again struggled to find evidence to support their priors. They found '21 studies on the influence of availability of alcohol from commercial sources on alcohol use', but, alas...

Overall the findings provided inconclusive results for the influence of availability on alcohol use, although some studies indicated that higher outlet density in a community may be associated with an increase in alcohol use.

With regards outlet density

specifically:

For off-premise outlets (such as shops), eight studies found no significant association but there is some indication that a higher density of off-premise outlets may be associated with an increased likelihood of heavy drinking.

For on-premise outlets (such as bars and restaurants), results were also mixed but there is some indication that a higher density of on-premise outlets may be associated with an increase in the likelihood of drinking and heavy drinking.

'Some indication' and 'may be associated' are not phrases to fill policy-makers with confidence and are a far cry from the bald assertions of efficacy you hear from the likes of Alcohol Focus Scotland when they appear on television.

As for local changes to licensing regulations...

Four studies (with four effect estimates) looked at the influence of local licensing changes on alcohol use, which included banning alcohol sales and making changes to the hours, days and volumes of alcohol sales that were licensed. They indicate that licensing restrictions may reduce alcohol use, but the evidence is not very robust.

This, remember, is from a group of people who are absolutely committed to clamping down on the advertising and availability of alcohol, and who are putting the best possible spin on the evidence.

Consumption of sugar-reduced products, as part of a blinded dietary

exchange for an 8-week period, resulted in a significant reduction in

sugar intake. Body weight did not change significantly, which we propose

was due to energy compensation.

It is often claimed that limiting the number of fast food outlets will reduce obesity, but dozens of studies have looked at the association between proximity to fast food outlets and obesity. The vast majority suggest that

there isn't one.

This week saw the publication of a systematic review of food advertising. Again, it was written by fervent interventionists and its lead author is the activist-academic Emma Boyland who is responsible for a fair chunk of the literature herself. She is now not only a professor but also an advisor to thee World Health Organisation.

You won't be surprised that she concludes that governments should restrict food advertising, but it is difficult much of a justification for this in her study.

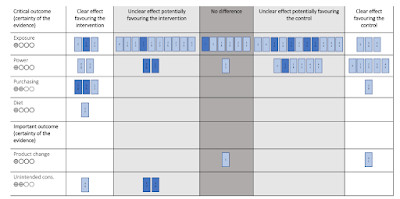

Evidence on diet and product change was very limited. The certainty of evidence was very low for four outcomes (exposure, power, dietary intake, and product change) and low for two (purchasing and unintended consequences).

Shown in a graphic, the evidence can most charitably be described as 'mixed'.

Their research, published in JAMA Pediatrics, found that

food marketing was associated with significant increases in food intake,

choice, preference, and purchase requests. However, there was no clear

evidence of relationships with purchasing, and little evidence on dental

health or body weight outcomes.

If food marketing doesn't have an effect on 'body weight outcomes', there is, of course, no point in restricting it. Obesity and dental health are the only outcomes we're interested in.

None of the studies mentioned above are libertarian hit jobs or industry debunkings. On the contrary, they are written by teammates marking each others homework. The ideological bias and statistical chicanery of many 'public health' researchers will be well known to readers of this blog. If they can't produce persuasive evidence that their policies work, even when reviewed by like-minded friends, we must seriously consider the possibility that none of this stuff does what it is supposed to.

.jpg)