Christopher Snowdon has now done what he failed to do in his original attack on lockdown sceptics in Quillette: he has engaged with the main plank of the sceptics’ case.

As I mentioned yesterday, the original article was never intended to be about the arguments for and against lockdowns. It was about the crackpots some lockdown sceptics have aligned themselves with. But now we have put all the stuff about false positives and casedemics behind us, we can get on with talking about the serious stuff.

In his response,

Chris starts by making a pretty big concession: he acknowledges that

the reduction in human interaction brought about by draconian

stay-at-home orders could be achieved by people just deciding

voluntarily to change their behaviour.

I don't see this as a 'concession'. On the contrary, it's an important part of my argument. It is obvious that people could stay at home without being told to. Toby thinks they would and that lockdowns are therefore superfluous, but if this were the case, you can't claim that lockdowns damage the economy. If you believe that nobody would go to the cinema during a pandemic, why complain about cinemas being closed? Would it not be better for the government to close them by law and compensate the owners and workers?

You can't have it both ways. Either lockdowns have little or no effect on behaviour and therefore do not damage the economy, or they have a significant effect on behaviour - and therefore on infection rates - and damage the economy.

I do think that lockdowns are economically damaging - very much so - but that's because I believe they have a big effect on people's behaviour. I think Toby knows they have a big impact on behaviour too. I think he knows that if you open the cinemas and restaurants, people will go to them and that this will lead to more people being infected. He is right when he say that 'it’s absurd to claim that people would have just carried on as normal in

the face of a global pandemic if they hadn’t been ordered to change

their behaviour'. The problem is that we don't seem to change our behaviour enough to get the R below 1.

This is partly because some people are downright irresponsible, but it is also because we don't have enough information upon which to act. Some people are wholly misinformed about the threat posed by the virus. The cranks I wrote about in my original Quillette article are partly to blame for that, but so too are public health agencies that have focused on handwashing rather than ventilation; the WHO flatly denied that SARS-CoV-2 was airborne in the early stages of the pandemic.

But the real problem is that the nature of the virus makes it very difficult for individuals to assess their risk. The insidious thing about COVID-19 is that the incubation period can last up to two weeks. The government has a nice

webpage where you can see how many people have recently tested positive in your postcode, but the figures are always five or six days out of date. You can think that your local area is low risk, but by the time you find out that it's high risk, it's too late.

You do not need to view the public as 'mouth-breathing troglodytes who will march towards their own destruction' to see that people cannot make an informed decision under these conditions.

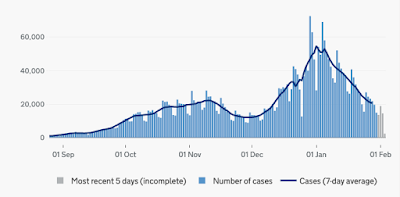

Moreover, for a lot of people COVID-19 is not a serious health threat and so we are relying on them to act in an essentially altruistic way. A person might decide that they don't care if they get it, but that is not a purely self-regarding action. We need to stop the spread. When you have 100,000 people being infected every day, as we did at the end of December, and have to get the rates down, you cannot depend on people acting sensibly, responsibly and altruistically. If you could, there wouldn't be 100,000 daily infections in the first place.

When we say that lockdowns are largely ineffective – largely, but not

completely – we are not questioning the basic logic of germ theory.

Rather, our contention is that the illiberal things governments across

the world have done in an attempt to control the virus have not resulted

in fewer people dying than if they’d taken a more liberal approach,

i.e., one that respected our individual rights and our status as

rational beings capable of carrying out our own risk assessments.

Judging by the people on my Twitter timeline yesterday, quite a lot of sceptics do seem to question germ theory. They do believe that the infection rate rises and falls of its own accord, unaffected by restrictions on human interaction. That is what I call the hard version of the 'lockdowns don't work' theory. Toby is talking here about the soft version. I addressed that in yesterday's post. To summarise:

- Countries which have a lot of COVID deaths are more likely to lock down harder and longer. The high death rates in Britain, Spain, France, etc. do not mean that lockdowns don't work in suppressing the virus, albeit temporarily.

- Plenty of countries locked down for a relatively short period of time, controlled their borders and have a low COVID death rate (Norway, China, Australia, New Zealand, Finland, etc.)

- Prolonged, sporadic lockdowns without achieving elimination are ineffective in the long term if there is no endgame, but we now have several vaccines. The debate about the current lockdown has to be seen in the context of the vaccination programme and yet Toby doesn't mention vaccines in either of his articles.

Having asserted that lockdowns do not lead to fewer people dying, Toby asks...

Why is that, given that lockdowns do reduce human interaction? As I said

in my piece, it may be because they bring about a net reduction in

overall interaction, but unintentionally increase it in particular hot

spots, where the virus is more easily transmitted. Or it could be

because the heavy-handed, authoritarian attitude of most states has

infantilized their populations, prompting them to take less

responsibility for not spreading the virus than they would have if

they’d been trusted to change their behaviour voluntarily.

Here, Toby seems to be conflating the hard and soft versions of the argument again. Lockdowns do reduce human interaction and they do reduce the infection rate. That has got nothing to do with the number of COVID deaths overall which are largely caused by infections that take place when lockdowns are relaxed.

|

Positive SARS-CoV-2 tests. England

|

I'm not quite sure what his argument is here, to be honest. If lockdowns make people increase their interaction with others in 'particular hot spots' or make them more irresponsible, shouldn't we see rates rising during lockdown?

Chris neglects to mention Sweden, which is not surprising because it

poses some very awkward questions for people who believe the Covid death

toll in Britain would have been far larger if we hadn’t imposed two

lockdowns last year.

I am happy to do so again.

Unlike some lockdown sceptics, Toby concedes that Sweden had significant excess mortality last year, but says this was partly due to there being fewer deaths than normal in 2019 (the so-called 'dry tinder' effect). And so he lumps 2019 and 2020 together and triumphantly concludes that the combined death count from 2017 and 2018 was similar to that of 2019 plus 2020.

I'll let the actuaries judge whether this is a reputable methodology. I would only point out that developed countries are supposed to see age-standardised mortality falling year-on-year and they usually do. There was nothing particularly special about 2019 in Sweden. The UK also had its lowest rate ever in 2019. This does not mean there is dry tinder waiting to go up in flames.

Nevertheless, it is true that Sweden did not see the conflagration some people predicted. I wrote about this in

September to make an anti-lockdown point. I was tired of people comparing Sweden to its immediate neighbours, all of which have

much lower rates of COVID mortality. I was bored of people claiming that Sweden had got off the hook because of its population density which is, in fact, no different to some countries that have been very badly hit.

My argument was that Sweden should be judged by its own standard. I pointed out that it had around 90,000 deaths every year and if it ended 2020 with 6,000 deaths from COVID - some of which would have happened anyway - it wouldn't be such a bad result in a once-in-a-century pandemic. The health service hadn't been overwhelmed. The Swedes had largely preserved their way of life, most of them seemed happy with the approach and in years to come, they, unlike most Europeans, will have something to say when they are asked what they did in 2020.

I wrote that...

The Swedes always accepted that they would see a higher rate of

mortality in the spring and summer than countries which locked down

early. The argument against lockdown was that every country would see a

similar number of deaths in the longterm and that it wasn't worth

disrupting people's lives and livelihoods in an extreme way by

quarantining the entire population.

I never endorsed the belief of some sceptics that Sweden had reached herd immunity, but I did think that it would enjoy

some protection in the winter from having allowed the virus to circulate among younger people in the summer. I wrote about this a week after the first lockdown ended in July,

saying:

One country can look to the winter with less trepidation than most. Last

week, a study suggested that 30 per cent of Swedes have built up

immunity to the virus. It would help explain why Covid-19 has been

fizzling out in Sweden. If a measure of herd immunity also helps them

avoid the second wave, Sweden’s take-it-on-the-chin approach will be vindicated.

We've all made bad predictions in the last year (

even Toby) and this was not one of my best. In my defence, I did conclude the article by saying that Sweden wouldn't look too clever if vaccines were produced in record time...

If a vaccine goes into production by autumn, the Swedes will look

reckless. But that is not going to happen - and winter is coming.

The vaccines didn't quite go into production in autumn, but it was close enough to make herd immunity by other means look a more questionable strategy.

Sweden has now had over 12,000 COVID deaths since the pandemic began and its second wave has been much worse than most. In

December,

99 per cent of Stockholm's intensive care beds were full. Finland and

Norway offered them medical assistance. The King of Sweden

said the country had failed. I expect the economy to have been badly hit. Although the infection rate has fallen recently, it is still above the EU average and is - as always - much, much higher than that of it neighbours.

Toby wants to know why it wasn't even worse. I would say it's because

the government pleaded with Swedes to keep themselves to themselves. Swedes are

advised to work from home and mix only with people they live with or with 'a small number of friends or people from outside your household'. Swedish people take such advice seriously, but there has been some stick as well as carrot. In December, the government

closed high schools and

told people to wear face masks on public transport.

Last month, the Swedish Parliament passed

new legislation to 'allow the authorities to close restaurants, shops, and public transport

in the country for the first time, and fine people who break social

distancing rules.' Large gatherings have been banned for months. Gatherings of more than eight people have been banned since November. The sale of alcohol is banned after 8pm. All of this and more has played a part in Sweden having merely one of the worst second waves rather than having the absolute worst.

Whatever the reasons, Sweden is not Britain, just as North Dakota isn't New York. It is a myth that Sweden has relied on voluntary measures, particularly in recent weeks, but insofar as voluntary measures have prevented the total catastrophe some predicted in Sweden, they have never shown any signs of doing so in Britain. [See the update at the bottom of this post for more on Sweden.]

I'm happy to judge Sweden by its own standard, but I also judge Britain by its own standard. We tried relying on people using common sense in the autumn and it didn't work. We then tried a tougher approach with the tiers and that didn't really work either. The tiers had an effect in some areas and probably flattened the curve overall, but they weren't enough to stop cases quadrupling in December when the B117 variant took off.

Our objective was to stop the NHS being overwhelmed. We failed. The infection rate rose and I am at a loss to see how adopting a more Swedish approach would have helped. By what mechanism would allowing more human interaction have slowed the spread?

Toby mentions again the US states that didn't lock down (although from a cursory look,

at least one of them pretty much did). He admits that they haven't performed quite as well as he may have implied earlier, but says that most of them didn't fare too badly. In fact, most of them fared worse than average, and the ones that didn't were the extremely rural states of Nebraska, Utah and Wyoming.

Why didn't North Dakota and Arkansas do even worse than New York and New Jersey on a deaths per million basis, he asks?

I don't know, but I would imagine population density has something to do with it. New York City is the busiest and most densely populated city in the USA whereas the biggest city in North Dakota, by some distance, is Fargo (population: 124,662). Being an international travel hub, New York was hit by a massive epidemic of COVID-19 last spring and locked down as a result (London was in the same position and it is another reason the UK was hit harder than Sweden). 70 per cent of all the COVID deaths in New York occurred during that initial outbreak. Surely you can't blame those deaths on the lockdown? The lockdown was a response to the deaths and

it worked well in bringing the numbers down.

Presumably the sceptics think New York made a mistake and should have let nature take its course. I cannot see how that would have helped. What practical lessons should we have learned from South Dakota and Sweden in December as the hospitals filled up in Britain? It is one thing to argue that more mixing between households wouldn't have done much harm, but how can anyone argue that it would have helped?

In the final analysis, the best comparison is between England with a lockdown and England without a lockdown. Toby has an answer for this and it is here that we see the 'hard' version of the 'lockdowns don't work' argument return. Having started his article by denying that lockdown sceptics believe that 'infections will rise and fall within a given region, irrespective of how much human interaction there is', Toby argues that it is not lockdowns that make rates fall, but nature.

[Snowdon] admits that it’s difficult to prove this is causation rather than

correlation, but claims that’s a more plausible hypothesis than the

alternative – “that it is sheer coincidence that lockdowns have been

accompanied by a sharp decline in case numbers in the UK and elsewhere

time and time again”.

But I don’t know anyone who thinks this is “sheer coincidence”.

Insofar as the decline in case numbers has coincided with lockdowns and

other NPIs – and didn’t predate their imposition, as it did in the case

of the UK’s first lockdown, which Chris more or less concedes – our

contention is that it’s due to seasonality (which is why infections

began to decline across Europe simultaneously last summer, regardless of

when different countries lifted their restrictions) and the fact that

the epidemic is beginning to settle into endemic equilibrium as more and

more people get infected and then recover.

Sorry, but how is that different from sheer coincidence? Toby is saying that seasonality causes rates to fall and that this happens to coincide with governments bringing in lockdowns.

It's a pretty ludicrous theory. Seasonality is a decent partial explanation for why COVID-19 rates stayed fairly low in the summer. It is not such a good explanation of why they fell dramatically in January.

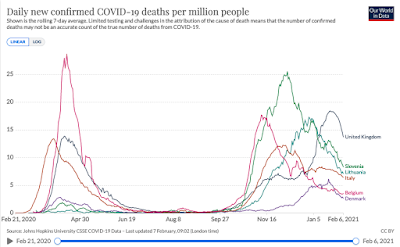

When, exactly, is Coronavirus Season supposed to be? It seems to be in October in Belgium, November in Slovenia, Lithuania and Italy, and December in Denmark and the UK.

Looking at case numbers, France seems to have had its coronavirus season in October, but the epidemiological curve has not declined in the way you would expect. Estonia's season is still ongoing with rates high and flat whereas Ireland's season was remarkably short and sharp, with the disease spreading over Christmas and suddenly declining after 31st December for some mysterious reason (spoiler: lockdown).

All of these countries saw massive spikes in deaths last spring which strongly suggests that the virus was spreading rapidly in February. This year, however, sceptics want us to believe that February is the time when the virus naturally fades away.

This is obviously nonsense. Seasons have an effect on SARS-CoV-2 only insofar as cold weather makes people more likely to be inside where viruses can spread more easily. It doesn't naturally disappear just because it's summer, let alone just because it's January. The number of COVID deaths has been rising in South America in recent weeks and South Africa has had a second wave in summer that was worse than the first wave in winter. Around the world, there have been major outbreaks in spring, summer, autumn and winter.

Toby concludes by saying that he enjoys debating me but that I need to 'stop tilting at straw men'. I enjoy debating him and I wish they were straw men. I wish he wasn't seriously claiming that the fall in infection rates seen around the world again and again at different times of year after lockdowns are introduced is the result of the seasons. This is not so much straw man and straw clutching.

I mentioned the

Google Mobility data in the debate. I find it fascinating. In Sweden, you can almost see the exact moment at which people's behaviour changed in late December, thereby leading to the decline in cases in January. You can also see the subsequent rise in movement which correlates with the current increase in cases.

This is evidence that people can change their behaviour voluntarily (albeit with a lot of nudging and a few regulations) in a way that brings case numbers down. But there are two things I find particularly interesting about this data.

Firstly, mobility fell to a record low in Sweden in late December. Even the current level is lower than it was last spring when rates were falling. In other words, the kind of behavioural change that was sufficient to bring case numbers down in the spring no longer seems to be enough, presumably because winter makes it less congenial to meet outdoors.

Secondly, look at the graph below, particularly November and December.

In the UK, mobility was more than 30 per cent below normal levels in December and

yet rates of infection were rising rapidly. In Sweden, they fell to that level in late December, but that was sufficient to bring rates

down.

This is just one measure of mobility, but all the others show a similar trend and a similar disparity between the two countries. It strongly suggests that even if the British had been able to reduce their mobility to Swedish levels voluntarily, it wouldn't have been enough to stop the rise in infections. This might be because of the B117 virus which is dominant in Britain or it might be something else. It could be any number of things. It is a reminder than Sweden and the UK are different countries. You cannot assume that what happens in one place will happen in another.

UPDATE

Lockdowns work by reducing human contact. If a country can sufficiently reduce human contact by other means, they should avoid lockdowns. Conversely, countries which cannot effectively enforce a lockdown are not going to sufficiently reduce human contact.

Human interaction is the key and

Google Mobility data is a good measure of it. In Sweden, you can almost see the exact moment at which people's behaviour changed in late December, thereby leading to the decline in cases in January. You can also see the subsequent rise in movement which correlates with the current increase in cases.

This is evidence that people can change their behaviour voluntarily (albeit with a lot of nudging and a few regulations) in a way that brings case numbers down. But there are two things I find particularly interesting about this data.

Firstly, mobility fell to a record low in Sweden in late December. Even the current level is lower than it was last spring when rates were falling. In other words, the kind of behavioural change that was sufficient to bring case numbers down in the spring no longer seems to be enough, presumably because winter makes it less congenial to meet outdoors and the B117 variant is starting to spread.

Secondly, look at the graph below, particularly November and December.

In the UK, mobility was more than 30 per cent below normal levels in December and

yet rates of infection were rising rapidly. In Sweden, they fell to that level in late December, but that was sufficient to bring rates

down.

This is just one measure of mobility, but all the others show a similar trend and a similar disparity between the two countries. It strongly suggests that even if the British had been able to reduce their mobility to Swedish levels voluntarily, it wouldn't have been enough to stop the rise in infections. This might be because of the B117 virus which is dominant in Britain or it might be something else. It could be any number of things. It is a reminder than Sweden and the UK are different countries. You cannot assume that what happens in one place will happen in another.

This can also be seen in the hospital data. The UK ended up with twice as many people in hospital with Covid (pro rata) than Sweden in January as a result of the pre-lockdown wave. The argument of lockdown sceptics is that people naturally modify their behaviour when the virus is getting out of control. If so, why did this happen in Sweden when it reached the

breaking point of 250 people per million in hospital, but not in the UK?

Notice the dip in hospital occupancy in the UK in November. That was the four week lockdown that began on November 5th. It is a clear cut example of a lockdown reducing cases, hospitalisations and deaths. We even have a suitable control group in the form of Wales, which locked down two weeks earlier and saw the same result two weeks earlier. A few lockdown sceptics have suggested that this, too, was an example of people modifying their behaviour naturally and that the drop in cases, hospitalisations and deaths would have happened anyway. It boggles the mind why people would suddenly behave this way in November but not when the situation was much worse in mid-December.

Lockdown sceptics who say 'cases would have fallen anyway' every time cases fall after a lockdown is introduced have finally found an argument that cannot be categorically disproved. It requires an extraordinary concatenation of coincidences around the world, but they will believe what they want to believe. It is understandable that they would use Sweden as a counter-factual since there are not many places that have avoided legal lockdowns, but while the Swedish approach might have worked for Sweden, all the indicators suggest that it wouldn't have worked for the UK. Indeed, it clearly didn't work for the UK when we tried a more 'Swedish' approach in December. We had more cases, more hospitalisations and more deaths, and, as the Google mobility data shows, it required a much greater suppression of human interaction to get the numbers down.