The National Health and Medical Research Council was responsible for issuing the advice and it has spent the last couple of years looking at the guidelines once more. You'll never guess what conclusion they've come to...

Two standard alcoholic drinks a day no longer safe, health officials say

National Health and Medical Research Council updates guidelines for first time since 2009 and says adults should average no more than 1.4 drinks a day

It's all rather predictable, isn't it? The new guidelines work out at about 12 UK units a week, even lower than the discredited British guideline of 14 units.

So, whose research was responsible for this implausibly low limit? Step forward our old friends at the Sheffield Alcohol Research Group, who were awarded the contract of modelling the safe drinking level. This was a bold move on the part of the National Health and Medical Research Council given that the Sheffield team were caught red-handed changing their methodology to allow Public Health England to lower the guidelines, but the Australian 'public health' industry is no more capable of feeling shame than our own.

The National Health and Medical Research Council knew what they were buying when they handed over the money and the Sheffield mob has not let them down. The name of the game is to exaggerate the risks of moderate consumption and downplay the benefits. Introducing their new model, they say...

New evidence on alcohol-related health risks has emerged since 2009. In particular, there is increased evidence that even low levels of alcohol consumption can increase drinkers’ risk of experiencing some types of cancer. An increased number of studies are also finding evidence that previous research may have overestimated any potential benefits to cardiovascular health that may arise from lower levels of alcohol consumption.

Four studies are cited to support the claim that 'previous research may have overestimated any potential benefits to cardiovascular health'. Two of them are Mendelian Randomisation (MR) studies looking at people who have an unusual genetic variant which affects alcohol consumption and risk. The relevance of this to western populations is debatable, to say the least. A recent study argues that the MR studies are not the get-out-of-jail card the temperance lobby has been waiting for, and MR studies may yet threaten the flimsy link between moderate alcohol consumption and breast cancer.

The third study is one of Tim Stockwell's numerous attempts to demolish the J-Curve (which shows lower rates of mortality among moderate drinkers than among teetotallers) by excluding studies he doesn't like and adjusting the results of the rest. See here for more on Stockwell's one man crusade.

The fourth and final one is the 2018 Lancet study which was reported to have debunked the J-Curve with this graph...

In fact, the study's findings actually supported the J-Curve if you could be bothered to go to page 31 of the appendix and the look at the graphs which didn't cheekily exclude the nondrinkers.

That, then, is the new evidence that shows that 'previous research may have overestimated any potential benefits to cardiovascular health'. Risible, but we should expect nothing more at this point.

Since 2019, there have been dozens of new studies confirming the benefits of moderate drinking, such as this, this, this, this, this and this, but most of them go unmentioned in the Sheffield report. Of course they do.

For their new model, they use risk estimates 'from published systematic reviews and meta-analyses of the epidemiological research literature'. All but two of their cancer estimates come from the World Cancer Research Fund, an organisation that has a naive view of ultra-low epidemiology and therefore thinks that nearly everything causes cancer. For prostate cancer, Sheffield uses one of Tim Stockwell's dodgy meta-analyses, presumably because even the World Cancer Research Fund doesn't think there's enough evidence to link it to alcohol. For non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma, which is without question inversely associated with alcohol consumption, they have to settle for a proper meta-analysis.

For heart disease, they use the 2016 meta-analysis by Yang et al. which showed a significant reduction in risk for people who drank moderately - and, indeed, heavily. It found that 36 grams a day (more than 4 UK units) conferred the lowest risk of coronary artery disease, with drinkers at this level being 31% less likely to suffer from it. Even at 135 grams per day (17 units) there was no increase in risk.

The Yang study shows this is a graph that is ugly but unambiguous. Teetotallers are at significantly greater risk of heart disease.

Avid readers of this blog will recall that the trick used to lower the UK drinking guidelines in 2016 was ignoring threshold effects, ie. pretending that light and moderate drinkers are at risk of serious alcohol-related diseases such as alcoholic liver cirrhosis and pancreatitis.

This had a big effect on the final results because lots of people are light/moderate drinkers and the diseases in question are often fatal. The problem is that light/moderate drinkers are at no extra risk of developing these diseases. None whatsoever. The Sheffield team know this, and we know that they know it because they said so when Public Health England asked them to change their methodology at the time.

Quite rightly, they e-mailed PHE to say that 'it does not seem right to assign people drinking at very low levels a risk of acquiring alcoholic liver disease and similar conditions'. But they did it anyway because PHE told them to - and paid them £7,800 for their trouble.

Changing your methodology at the 11th hour - in a way that you know to be wrong - on the orders of your funder would end most scientists' careers, but the world of 'public health' is a little different. Rather than being kicked out of the academy, the Sheffield Alcohol Research Group has been awarded numerous grants, including this job in which they returned to the scene of the crime.

And they've done exactly the same thing...

In the base case model, we assume this consumption threshold is zero for both chronic and acute conditions (i.e. that risk increases with any level of alcohol consumption) in line with the work undertaken as part of the 2016 UK drinking guidelines review.

Of course they do. This allows them to produce risk curves for diseases which only affect people who drink a great deal of alcohol which look like this...

And this...

In their sensitivity analysis, they model a scenario in which moderate drinking has no protective effects at all, a ridiculously unrealistic proposition which they nonetheless imply might be true throughout the text.

Also in the sensitivity analysis, they model a scenario in which there are threshold effects for some diseases - which is nice of them given that it happens to be true - but they set the thresholds at a ludicrously low level (4 UK units for men and 3 UK units for women per week!). In other words, drinking more than two pints of beer a week puts you at increased risk of alcoholic liver cirrhosis. It doesn't, of course, but this is 'in lines [sic] with the previous UK analysis' so that's OK.

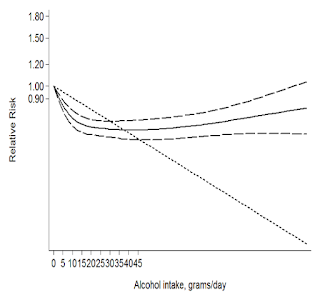

As a result of this tampering - and their decision to make heart disease 'the only condition where we adjust a literature-based risk function' - they produce an overall risk curve which should look something like this...

But which looks like this...

Sheffield's model therefore suggests a 'safe drinking level' of under 15 standard drinks a week. This is similar to the model they produced for the UK. This is hardly surprisingly as it is essentially the same model with a few adjustments made for demographics and health status.

But we know the UK model is worthless, and even the Sheffield team don't believe one of its key assumptions, so why did the Australian public health industry pay them to make the same mistakes again?

Hmm, let me see...

The next step is a public consultation running until 24 February but that will doubtless be a rubber-stamping exercise. Regardless of the evidence, alcohol guidelines only go in one direction and, as I have long argued, will one day go to zero.

No comments:

Post a Comment