In a particularly bizarre column three years ago, he demanded a ban on the sale of sweets to children, amongst other things...

Ban fast-food outlets from stations and airports. Ban the sale of confectionery and sugary drinks to the under-16s. Ban the sale of over-sugared products in supermarkets (as measured by a ratio of sugar to other nutrients). Ban the bringing into schools of unhealthy foods. Ban the presence in offices (like our own here at The Times) of vending machines that seem to sell mainly crisps and chocolate. Specify a weight-to-height ratio limit on air passengers wishing to avoid a surcharge.

This all seems outlandish and dictatorial at the moment. So too, back in the late 1980s, did the idea that you wouldn’t be allowed to smoke on planes.

No slippery slope, etc.

Last week he was back with an article that attempted, in all seriousness, to portray Prohibition as a success. It's a rarely heard point of view but not wholly unprecedented. People in 'public health' occasionally try to rewrite the history of 1920-33 to justify their own lurch towards prohibition, whether it be with tobacco, vaping or alcohol itself.

The basic argument is that alcohol consumption fell between 1920 and 1933. Well, duh. That is not contested. The reason that the 18th Amendment is the only one to have gone through the difficult process of repeal (requiring the consent of two-thirds of US states) is that there are more important things than per capita alcohol consumption. Murder, for one. Organised crime for another. Thousands of people being blinded, crippled, poisoned and killed for another. I addressed the silly, galaxy brain argument that 'prohibition worked, actually' in The Art of Suppression.

Aaronovitch doesn't bring anything new to the table and seems to have done very little research into the arguments he has microwaved, but let us quickly run through them.

Prohibition showed bans can be good for usOutlawing alcohol 100 years ago led to a boom in bootlegging but it also had a striking effect on public health.. Excessive alcohol consumption is linked to all kinds of adverse health conditions. The most obvious is alcoholic cirrhosis (or scarring) of the liver. In 1911 the death rate for cirrhosis among American men was nearly 30 per 100,000. By 1929 that had been reduced by more than 30 per cent.

There was certainly a steep fall in the mortality rate from liver cirrhosis in the early twentieth century, but the bulk of it took place before Prohibition began in 1920. At no point was the rate 'nearly 30 per 100,000'.

What caused this precipitous decline? Plenty of states had gone dry by the time the US imposed national Prohibition so we can't discount the firm hand of government entirely, but the most likely candidate is the First World War. The same thing happened in Canada, France, Britain and, I dare say, a few other European countries too.

Forgive the mad y-axis, but you get the picture.

You can, if you are inclined, use these graphs as evidence that making alcohol hard to come by reduces alcohol-related mortality, but note that the UK saw liver cirrhosis deaths fall from 9 per 100,000 to 5 per 100,000 before the war began. You don't need rationing, let alone Prohibition, for outcomes to improve.

You can, if you are inclined, use these graphs as evidence that making alcohol hard to come by reduces alcohol-related mortality, but note that the UK saw liver cirrhosis deaths fall from 9 per 100,000 to 5 per 100,000 before the war began. You don't need rationing, let alone Prohibition, for outcomes to improve.

Registered admissions to mental hospitals for psychosis linked to alcohol more than halved.

I'm not sure where he got this statistic, if anywhere. The US Census Bureau didn’t start collecting statistics on admissions to mental hospitals until 1923, so we can't compare with the pre-Prohibition era.

One historian has suggested that short-term stays in mental institutions in New York fell prior to prohibition, and then rose after it...

I don't think the evidence exists to support or debunk Aaronovitch's claim.

Yes. The best guess is that consumption went down by two-thirds when Prohibition began and then rose until it was only a third lower than it had been when alcohol was legal. Not too impressive, really.

The point shouldn't need underlining, but the fact that Prohibition was flouted by scofflaws (a word invented in the 1920s) on such a grand scale is evidence that Prohibition was not wanted.

One historian has suggested that short-term stays in mental institutions in New York fell prior to prohibition, and then rose after it...

'In 1904, 27.8 percent of the nation's total patient population had been institutionalized for twelve months or less. This percentage fell to 12.7 by 1910, rising to 17.4 in 1923.'

I don't think the evidence exists to support or debunk Aaronovitch's claim.

Even by 1933, when Volstead was revoked, alcohol consumption had gone down by a third since pre-prohibition.

Yes. The best guess is that consumption went down by two-thirds when Prohibition began and then rose until it was only a third lower than it had been when alcohol was legal. Not too impressive, really.

The point shouldn't need underlining, but the fact that Prohibition was flouted by scofflaws (a word invented in the 1920s) on such a grand scale is evidence that Prohibition was not wanted.

Whatever Mark Twain may have written, prohibition saved many, many lives.

Mark Twain died in 1910. Perhaps Aaronovitch is confusing him with one of the tens of millions of Americans who thought that Prohibition was a disaster.

But what about the extra crime and the corruption it caused? In fact there was no big increase in homicide or violent crime in the era of prohibition.

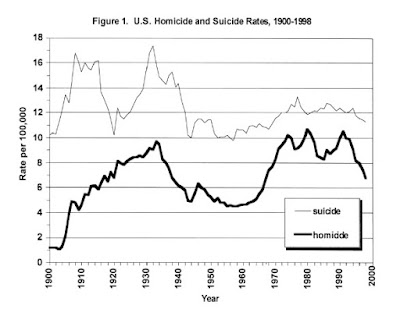

Er, yes there was. The homicide rate rose throughout the era of Prohibition and fell sharply as soon as it was repealed. The increase in crime and violence was well recognised at the time and was one of the main reasons Prohibition was repealed.

Incidentally, the suicide rate - which, unlike the homicide rate, had been falling before 1920 - also rose throughout Prohibition and fell afterwards.

He continues...

True, mobsters — who existed long before the ban — pitched into liquor smuggling, but when prohibition was over they just moved on to other things.

And how lucky they were that the USA had launched the war on drugs in the meantime, thanks to many of the same characters who had given it the war on alcohol. The more opportunities you give organised criminals, the more organised crime you're going to get.

In the meantime arrests for public disorderliness due to drink fell by half, as did recorded complaints of domestic abuse (almost invariably violence by a drunken man against his partner or family).

Domestic abuse (or ‘wife beating’) was made illegal in 1920 in all US states. Ramsey says that...

'.. the likelihood that a wife beater would be incarcerated at least briefly seems to have been high in the 1920s'.

This doesn’t directly contradict Aaronovitch’s claim, but I can't find support for it in this detailed history of American domestic violence which is surprising if it is true – a halving of domestic violence rates in 10 years would be remarkable.

His factoid about drunk and disorderly arrests also seems dodgy:

'The Volstead Act, passed to enforce the Eighteenth Amendment, had an immediate impact on crime. According to a study of 30 major U.S. cities, the number of crimes increased 24 percent between 1920 and 1921. The study revealed that during that period more money was spent on police (11.4+ percent) and more people were arrested for violating Prohibition laws (102+ percent). But increased law enforcement efforts did not appear to reduce drinking: arrests for drunkenness and disorderly conduct increased 41 percent, and arrests of drunken drivers increased 81 percent.'

He then notes, correctly, that Prohibition had some positive lasting effects. It changed saloon culture beyond recognition and normalised female drinking in bars, for instance.

Finally, though prohibition was abolished and the renascent drinks manufacturers blitzed the public with booze ads and the film-makers with glitzy party scenes, it has lingered on in reduced consumption, state bans and — as I discovered aged 60, ordering a cocktail in the Lower East Side — stringent age checks.

Maybe, but as Lisa McGirr shows in her book The War on Alcohol, it also revived the Ku Klux Klan, normalised police raids on private property, created the template for the FBI and led to the creation of the modern, heavy-handed American penal state. So, swings and roundabouts.

Aaoronvitch's motive for resurrecting the failed experiment of Prohibition is, as you might have guessed, to push some lesser restrictions on drinkers. He cites Public Health England's amateurish, error-strewn report on alcohol policy that was published at the fag end of 2016.

Although there has been a slight decline in alcohol consumption in England and Wales in the last decade, that followed an increase of more than 40 per cent between 1980 and 2008.

Per capita alcohol consumption is almost exactly where it was in 1980.

In June 2012 the Scottish government began to legislate for minimum alcohol pricing aimed at reducing consumption through incentives. Last year a BMJ study concluded that the effects of a 50p per unit minimum cost had reduced consumption by 1.2 units per week, and two units among the heaviest drinkers.

It wasn't last year. It was six weeks ago and the claims in the study bear no resemblance to the sales figures.

But enough of this. Prohibition didn't work 100 years ago and it won't work next time.

No comments:

Post a Comment