New statistics from the Gambling Commission were published last week and they make for interesting reading. You may recall that the stake limit on fixed-odds betting terminals (FOBTs) was reduced to £2 in 2019, which amounted to a de facto ban since hardly anybody wants to play them with such a low stake.

Advocates of the reform said it would reduce gambling-related harm by making it more difficult for machine gamblers to lose large sums of money. There was also a suggestion that it would reduce the number of problem gamblers.

Opponents said that it would lead to the closure of thousands of betting shops and that problem gamblers would switch to other gambling machines and go online.

The pandemic has made it difficult to make a simple before-and-after comparison because physical gambling venues were closed for long periods between March 2020 and July 2021. The financial year 2020/21 was a write-off and 2021/22 was partially affected by a lockdown. Even 2019/20 was slightly affected, with venues closed for the last 10 days of that year.

Nevertheless, there is enough evidence for some obvious changes in the gambling market to be identified. The table below gives an overview of the sector (click to enlarge).

The FOBT reform was introduced in April 2019. Overall Gross Gambling Yield (which basically means revenue: stakes minus prizes) fell slightly in 2018/19 and fell again in 2019/20. Bookmakers were the big losers, with GGY falling from £3.3 billion to £2.4 billion in this period.

By contrast, online casino GGY rose from £2.9 billion to £3.2 billion and then shot above £4 billion in the first year of the pandemic. Online betting revenue rose by £300 million in the first year of the FOBT change, having fallen the previous year.

It's difficult to call cause and effect in an evolving market but this data is consistent with the prediction that online gambling would pick up some of the slack from the fall of the FOBTs.

In the betting shop sector, there is clear evidence of a massive switch from FOBTs (formally known as B2 machines) to high jackpot machines (B3 machines). In 2017/18, there were 33,685 B2 machines in bookies and just 31 B3 machines. By 2021/22, there were just seven (!) B2 machines and 24,339 B3 machines.

Over the same period, Gross Gambling Yield from B2 machines fell from £1.7 billion to £110,000 while GGY from B3 machines rose from £158 million to £1.1 billion. Overall gaming machine revenue declined by 42 per cent. It should be remembered that 2021/22 was affected by lockdown. Nevertheless, there is little doubt that betting shops are making significantly less from gambling machines than they were as a result of the disappearance of FOBTs.

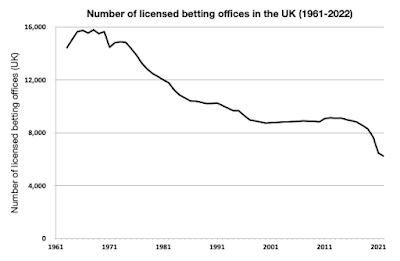

The other striking change is the number of betting shop closures. 2,300 bookmakers have disappeared since the FOBT reform. There are now 6,219 betting shops in the UK, which is half as many as there were in 1980. And there are more to come if yesterday's announcement from the new owner of William Hill is anything to go by.

An unpublished report by KPMG commissioned by the bookies predicted that 4,500 betting shops would close if the FOBT stake was reduced to £2. So far, it has been around half of that, but it has been a hell of a lot more than the few hundred predicted by anti-gambling campaigner Matt Zarb-Cousin.

Incidentally, and contrary to the notion that gamblers in betting shops would switch to

betting on the horses, revenue from horse-racing continued to fall in 2019/20 with turnover (i.e. the amount wagered) falling below £4 billion for the first

time.

I can't find figures for employment, but I believe 53,000 people were employed in the bookmaking industry in 2018. With a quarter of betting shops closing, a rough estimate would be that around 13,000 people have lost their jobs.

As for problem gambling, the Commission's latest figures give the following estimates:

Year to September 2018: 0.5%

Year to September 2019: 0.5%

Year to September 2020: 0.6%

Year to September 2021: 0.3%

Year to September 2022: 0.3%

On the face of it, the rate of problem gambling halved between 2020 and 2021. This is possible, but it seems very unlikely. While this decline doesn't exactly correlate with the timing of the FOBT reform, anti-gambling campaigners could say that it is consistent with the prediction that the number of problem gamblers would fall once the 'crack cocaine of gambling' was banished from Britain. I haven't heard any of them make that claim, presumably because they are now crusading against online gambling and don't want to give the impression that things have got better.

The Betting & Gaming Council, by contrast, have been shouting about the low prevalence figure. This is probably a mistake. The problem gambling rate has been estimated at between 0.3% and 0.9% ever since it started being recorded in 1999. There has never been a sustained rise or decline. The fluctuations from year to year are probably meaningless. Although the Gambling Commission surveys 4,000 people, there are so few problem gamblers that the confidence interval is enormous (+/- 1.5%!). In the latest survey of 4,018 people, only 11 of them were problem gamblers.

As a consequence, none of the year-to-year changes are statistically significant. It is perfectly likely that the next survey will find a prevalence of 0.6%, in which case anti-gambling campaigners (and The Times) will claim that the number of problem gamblers has doubled. That, too, will almost certainly be nonsense.

In summary, the radical stake reduction on FOBTs was associated with gamblers in betting shops suddenly spending £1.1 billion on machines that most people have never heard of, but spending less on machines as a whole. There is a strong suggestion in the data that some FOBT spend was displaced online. A quarter of the UK's betting shops closed. British gamblers may be spending slightly less overall, but we will have to wait for the 2022/23 post-pandemic figures to be published before we can say that with any certainty.

No comments:

Post a Comment