|

| Promises, promises |

Minimum pricing of alcohol in Scotland is not going well. Self-styled public health advocates are baffled.

.. no changes in the trend direction or statistically significant changes in the level of all alcohol-related crime and disorder

The odds ratio for an alcohol-related emergency department attendance following minimum unit pricing was 1.14 (95% confidence interval 0.90 to 1.44; p = 0.272). In absolute terms, we estimated that minimum unit pricing was associated with 258 more alcohol-related emergency department visits (95% confidence interval –191 to 707) across Scotland than would have been the case had minimum unit pricing not been implemented.

There is no clear evidence that MUP led to an overall reduction in alcohol consumption among people drinking at harmful levels or those with alcohol dependence, although some individuals did report reducing their consumption.

People drinking at harmful levels who struggled to afford the higher prices arising from MUP coped by using, and often intensifying, strategies they were familiar with from previous periods when alcohol was unaffordable for them. These strategies typically included obtaining extra money, while reducing alcohol consumption was a last resort.

MUP led to increased financial strain for a substantial minority of those with alcohol dependence as they obtained extra money via methods including reduced spending on food and utility bills, increased borrowing from family, friends or pawnbrokers, running down savings or other capital, and using foodbanks or other forms of charity.

Some people with alcohol dependence and their family members reported concerns about increased intoxication after they switched to consuming spirits rather than cider. In some of these cases, people also expressed concerns about increased violence.

Alcohol-related hospital admissions refused to decline after the policy was introduced and alcohol-related deaths are at a nine-year high, although lockdowns doubtless had an affect on the latter. The policy cost Scottish drinkers £270 million in its first four years and all the SNP have to cling to is a modest drop in alcohol consumption, much of which is due to COVID-19.

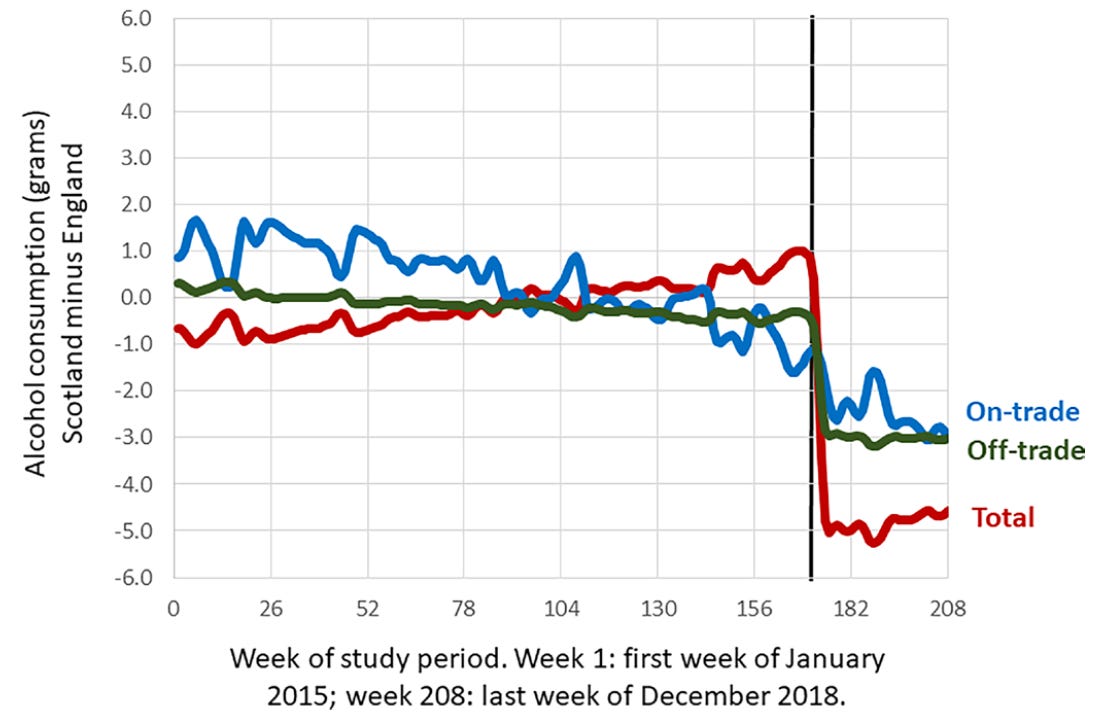

Last month, a new piece of research was published in BMJ Open looking at alcohol consumption. It was not part of the official evaluation and was produced by academics who are very sympathetic to minimum pricing. They nevertheless struggled to make the policy look like a success.

It looks like an impressively steep decline until you realise that 5 grams of alcohol is barely half a unit. Per week. And the reduction in consumption from the off-trade, which is the only place minimum pricing makes any difference, was just 3 grams.

The reductions in consumption are largely driven by women (a reduction of 8.6 g per week, 95% CI 2.9 to 14.3) rather than by men (a reduction of 3.3 g per week, 95% CI –3.6 to 10.4)

For the 95th percentile the introduction of MUP was associated with an increase in consumption for men of 13.8 g (95% CI 5.8 to 21.5), but not for women (4.8 g, 95% CI −4.0 to 13.7).

For younger men there was an increase in off-trade consumption, which was offset by decreases in on-trade consumption in the same group.

None of these findings are terribly surprising to people who are more worldly than your average ‘public health’ academic. Raising the price of cheap booze was always more likely to change the behaviour of moderate tipplers than heavy drinkers. Hardcore drinkers were always going to find money to keep drinking and minimum pricing was never going to help the pub trade. It was only likely to make the poor poorer.

When the Minister for Public Health, Sport and Wellbeing introduced the 2018 alcohol policy framework, he emphasised that the implementation of the MUP [minimum unit price] was strongly motivated by an interest in decreasing health inequalities through a reduction in alcohol consumption among the heaviest and most vulnerable drinkers. Our results indicate that this goal may not be fully realised…

… first, we found that women, who are less heavy drinkers in our data and in almost all surveys worldwide to date, reduced their consumption more than men; second, the 5% of heaviest drinking men had an increase in consumption associated with MUP; and, third, younger men and men living in more deprived areas had no decrease in consumption associated with MUP. These results are surprising as modelling studies would have suggested otherwise.

We do not know why, for both younger men (those aged <32 years) and for those living in residential areas in the bottom two-fifths of deprivation, there was no decrease in consumption associated with MUP compared with older men and those living in less deprived areas.

Several studies have found that overall, heavier drinkers— including people with alcohol use disorders—react less to price than the general population (ie, they react more price inelastic and their consumption is determined by other factors). However, while this may explain lower reductions, it cannot explain an increase in consumption.

The results may also imply a diminished impact on alcohol-attributable hospitalisations and mortality, which have been shown to be strongly associated with heavy drinking in men and in those of lower socioeconomic status. Indeed, a large controlled study on emergency department visits following the introduction of MUP did not show any reduction in alcohol-related emergency department visits.

In a sensational act of hubris, three activist-academics published an article in 2017 claiming that the evidence-base for minimum pricing, a policy that had never been tried anywhere, fulfilled the great epidemiologist Austin Bradford Hill’s criteria for causality. It seemed absurd at the time and it seems almost grotesque now.

If indeed the findings of our study are corroborated, then additional and/or different pricing mechanisms may need to be considered to reduce alcohol-attributable hospitalisations and mortality.

‘Tis but a flesh wound!

Postscript

Following the introduction of MUP, total household food expenditure in Scotland declined by 1.0%, 95%CI [-1.9%, − 0.0%], and total food volume declined by 0.8%, 95%CI [-1.7%, 0.2%] compared to the north of England.

There is variation in response between product categories, with less spending on fruit and vegetables and increased spending on crisps and snacks.

No comments:

Post a Comment