Dick Puddlecote has written a pretty thorough critique of the first effort, the conclusion of which was that plain packs have inspired smokers in New South Wales to call the Quitline en masse. The authors make no attempt to disguise the fact that their study is designed to encourage gullible politicians in other countries to emulate Australia's folly...

We found a significant increase in the number of calls to Quitline coinciding with the introduction of mandatory plain packaging of tobacco after other known confounders had been taken into account. Australia has taken a lead on mandating plain packaging, now supported by evidence of an immediate impact of this legislation. This should encourage other countries that are preparing similar legislation.

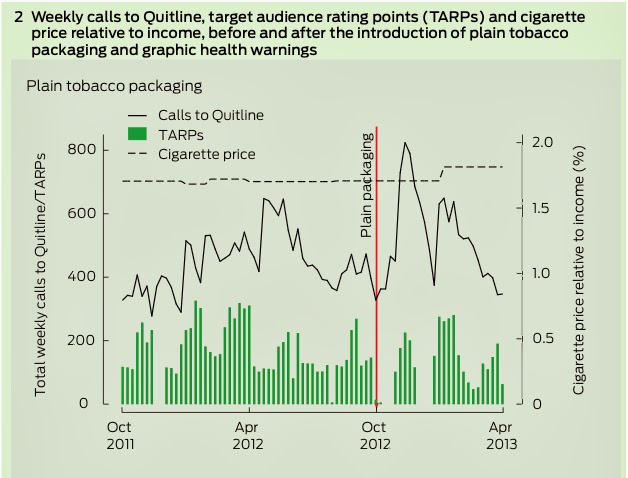

The reality is much less impressive. The graph below shows the weekly number of calls to the Quitline before and after plain packaging:

Clearly, the number of calls to the Quitline vary considerably over time. There is a spike in mid-2012 (for reasons I can't explain) followed by a spike when plain packaging was rolled out, and another spike when tobacco taxes rose in 2013. Calls to quitlines frequently do rise temporarily when changes are made to packaging and pricing so this is no great surprise. Moreover, the Quitline number is prominently advertised on the new packs. Nevertheless, the plain packs spike is no greater than you would expect from a mere rotation of the warnings or a new anti-smoking campaign on TV. Bringing in plain packaging is a hell of a lot of effort to go to for such a brief and modest outcome.

A few hundred extra people calling a phone number (in a state with a population of seven million) is not particularly newsworthy. We know that quitlines of this sort are a wildly expensive and inefficient way of helping people to quit and that their success rate is woeful. There was a similar spike in 2006 when graphic warnings were introduced (see below), but we now know that the effect of graphic warnings on smoking rates is "negligible".

And look at the numbers involved in both these graphs! When graphic warnings were introduced, the number of weekly calls to the Quitline hit 3,000 and regularly stayed above the 1,000 mark. By the time plain packaging came about, numbers peaked at 800 and were lingering around the 400-500 mark both before and afterwards. (There was a small drop in the number of smokers between 2006 and 2012, and therefore fewer potential customers for the Quitline, but nowhere near enough to explain why so few people were calling the Quitline by the time plain packs came in.)

In short, graphic warnings—which have a negligible effect on smoking rates—inspired many more people to call the Quitline than did plain packaging. If plain packaging cannot replicate even that modest outcome, the chances of it having any meaningful impact on smoking rates are very small indeed.

The second study, published today in Addiction, is even weaker. In this effort, a team led by longstanding plain pack campaigner Melanie Wakefield, hung around outside bars

The proportion of packs oriented face-up declined from 85.4% of fully-branded packs pre-PP to 73.6% of plain packs post-PP (IRR=0.87, 95% CI=0.79-0.95, p=.002).

It's always amusing to see confidence intervals inserted into crude surveys to give the appearance of scientific rigour, but it should be clear that the difference between 85% of smokers placing their packs face up against 74% is utterly trivial. (I hesitate to assume that the authors believe that people start smoking because they see the front of cigarette packs on tables in bars, but the sky is the limit when dealing with anti-smoking nuts.)

The authors claim that there was a 15% decline in the number of cigarette packs seen on tables outside bars after plain packs came in. Of course, if smokers are concealing their packs in pockets and bags, the authors can't always know whether they are smokers. This is a bit of a methodological problem, to say the least, but the press release nevertheless makes the following remarkable claim...

[The researchers] found that pack display on tables declined by 15% after plain packaging, which was mostly due to a 23% decline in the percentage of patrons who were observed smoking.

The first part of this sentence is roughly believable. It's possible that a few smokers would keep the new packs out of sight or put their cigarettes in cases (the researchers find a three-fold increase in the use of cigarette cases).

The second part—that the number of people smoking fell by 23%—is simply impossible to believe. If the smoking rate has fallen by 23% in Australia since plain packs came in, I will retract everything I've ever said about this ridiculous policy. But it hasn't. It doesn't seem to have dropped at all.

So, while it would make sense to see fewer cigarette packs lying around when there are fewer smokers present, that is all the researchers have observed. I can't explain why they saw fewer smokers in their second survey, but it sure as hell ain't because their numbers fell by 23% or even 2.3%. Something is badly at fault with the methodology here that renders the observations about the number of packs seen on tables meaningless.

All of this is irrelevant flim flam in any case. Surely enough time has passed for us to see some real data. Was there a big drop in the number of young people taking up smoking in 2013? Was there an unusually large decline in the overall smoking rate in 2013? These are the real questions but, via Mr Puddlecote, I see that these questions are being scrupulously avoided.

A global study out today has found that after decades of declining, Australia’s rate of smoking has plateaued, and even increased slightly among women. There are almost 3 million smokers in Australia and between them they puff on 21 billion — yes, billion — cigarettes a year.

That’s the most recent data available, and it goes up to the end of 2012. As to whether the world’s first laws mandating the plain packaging of cigarettes have worked (they started in December 2012), those who have the data won’t release it. It’s a public policy secret.

A barrage of policy-based pseudo-science is being used to obscure us from the facts of what has really happened in Australia. Eventually, the truth will out. In the meantime, if you want to get an idea of what the real impact of plain packs has been, consider this...

Victoria has declared war on illegal cigarettes, with fines quadrupled for any retailers caught selling dodgy smokes.

The unprecedented crackdown comes as authorities begin destroying a record haul of 71 tonnes of illegal tobacco and 80 million cigarettes, seized on arrival in Melbourne by ship.

Health Minister David Davis will today announce the huge rise in fines for retailers caught with chop chop, counterfeit or contraband tobacco or cigarettes.

The new penalties, expected to be in place later this year, will see individuals facing fines of $34,600 and businesses $173,200.

Now, why would the government need to be doing this if everything was fine and dandy in the brave new world of plain packaging?

1 comment:

Wait: if they observed 23% fewer smokers (for whatever reason) and just 15% fewer packs displayed on tables, that means that smokers tend to show up their packs more often than before.

Post a Comment