The incompetent and corrupt World Health Organisation has produced a ‘guide for journalists’ to help hacks report on issues related to alcohol accurately. Not entirely unpredictably, it is a catalogue of anti-drinking tropes, half-truths and brazen lies. The very first words are ‘No amount of alcohol is safe to drink’ and it doesn’t get any better thereafter.

The health benefits of moderate alcohol consumption really stick in the craw of the neo-temperance lobby and so that is where the WHO starts:

Isn’t drinking some alcohol good for your health?

No, there is no evidence for the common belief that drinking alcohol in moderate amounts can help people live longer by decreasing their risk of heart disease, diabetes, stroke or other conditions.

No evidence?! Even a casual follower of the science knows that there is at least some evidence. Those who are more familiar with the literature know that there is a huge amount of evidence built up over decades, tested and re-examined from every angle precisely because so many people in ‘public health’ don’t want to believe it.

It is inaccurate to say that “experts are divided” on whether there is no amount of healthy alcohol drinking. The scientific consensus is that any level of alcohol consumption, regardless of the amount, increases risks to health.

This is just a lie. That is not the consensus, and the only reason there isn’t unanimous agreement that moderate drinking is beneficial to health is that anti-alcohol academics such as Tim Stockwell have made it their life’s work to cast doubt on the evidence.

While several past studies did suggest that moderate consumption could, on average, promote health benefits…

Note that this immediately contradicts the claim that there is no evidence.

… newer research (1) shows that those studies used limited methodologies and that many of them were funded by the alcohol industry (2).

The first reference is a short commentary by some WHO staffers which doesn’t discuss methodologies at all. The second reference is a study which found that only 5.4 per cent of research papers in this area were funded by the alcohol industry and concluded that ‘the association between moderate alcohol consumption and different health outcomes does not seem to be related to funding source.’

The WHO must hold journalists in low esteem if it thinks they won’t check up the citations like this.

The dicussion [sic] about possible so-called protective effects of alcohol diverts attention from the bigger picture of alcohol harm; for example, even though it is well established that alcohol can cause cancer, this fact is still not widely known to the public in most countries (3).

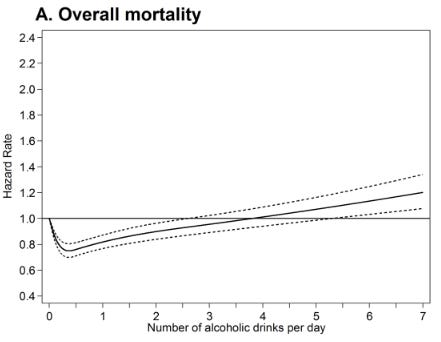

The ‘bigger picture’ is overall mortality. When all the risks are taken into account, including the small risks from a few rare cancers, do moderate drinkers live longer than teetotallers? Yes. Yes, they do.

But what about reports that a daily glass of red wine is good for your heart?

There is no good evidence for the pervasive myth that consuming red wine helps prevent heart attacks.

Note that they’ve shifted from ‘no evidence’ to ‘no good evidence’. It seems that no evidence is good unless it shows that drinking at any level is a killer.

The main reason that moderate alcohol consumption reduces overall mortality is that it substantially reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease. The evidence for this is not just ‘good’. It is overwhelming. For example, this meta-analysis of 84 studies concluded that: ‘Light to moderate alcohol consumption is associated with a reduced risk of multiple cardiovascular outcomes.’ The risk of cardiovascular disease mortality was 25 per cent lower than among non-drinkers.

Since red wine is a form of alcohol, it would be very odd if drinking a moderate quantity of it wasn’t good for the heart. All the evidence shows that it is, and there are some reasons to think that it might be even better than other forms of alcohol in this respect.

Why are national drinking guidelines different from WHO recommendations?

Many countries have issued low-risk guidelines, usually recommending no more than 10 standard drinks per week. WHO does not set particular limits because the evidence shows that the ideal situation for health is not to drink alcohol at all.

Again, this is simply a lie.

Doesn’t most alcohol harm come from a minority group of heavy drinkers?

The common perception is that a small fraction of the population causes most of the harm linked to alcohol consumption. But alcohol-related cancers, accidents, injuries and violence are widely distributed across the population (8), including among those who drink moderately. Even though heavy drinkers are undoubtedly at high risk of alcohol-related harm, they contribute only a minority to the total alcohol casualties. In this “prevention paradox”, most alcohol-related harm occurs among low-to-moderate risk drinkers simply because they are more numerous in the population.

This is a reference to one of the ideas of Geoffrey Rose who argued that there are more deaths from a large number of people exposed to a low risk than from a small number of people exposed to a large risk. While this could be true of some risk factors in certain circumstances, it is not a general rule and it is particularly poorly suited to alcohol because the risk of low to moderate consumption is negative, i.e. it is beneficial.

‘Alcohol-related cancers’ are relatively rare and mostly affect heavy drinkers. It is reasonable to assume that most drink-related ‘accidents, injuries and violence’ also involve heavy/binge drinkers. The prevention paradox just doesn’t apply to alcohol and Rose never claimed it did. Some academics have tried to claim otherwise, but they have had to narrow their scope to a limited range of ‘harms’ and portray people who get drunk as moderate drinkers to do so.

The real reason why organisations like the WHO are so keen to pretend that everybody is at risk from alcohol harm and there is no safe level of drinking is that it can be used to justify population-wide policies such as minimum pricing (which the WHO’s new report wrongly describes as ‘effective’). They say this in so many words in the summary:

Takeaway

Alcohol consumption causes considerable harm to millions of people across the world, not just the heaviest users, which is why strong global action that protects the entire population is needed.

Why, you may ask, is the WHO taking such a hard line on this that it is prepared to lie to our faces? Preaching total abstinence is a departure for the WHO. It is not what most of its member states expect of it and it is out of line with its previous messaging.

Part of the reason is that some member states do support total abstinence. You have to remember that alcohol prohibition is still a reality in some countries. Several other countries, such as India and Turkey, allow the sale of alcohol but strongly discourage it. Russia and some of the Baltic states have been clamping down on alcohol in a big way in recent years. The WHO has to represent all these interests.

The bigger and more important reason is that anti-alcohol activists have weaseled their way into the WHO in growing numbers. A lot of WHO reports are written anonymously. This one isn’t, and its list of contributors is very revealing. They include:

Phil Cain, European Alcohol Policy Alliance (Eurocare)

Florence Berteletti, Eurocare

Phil Cain is a former BBC journalist who has been tweeting about alcohol for years and has become increasingly fanatical. I didn’t know he was now at Eurocare but it makes sense. Eurocare is an EU-funded temperance pressure group formed in 1990 by the Methodist teetotaller Derek Rutherford.

Maik Dünnbier, Movendi International

The International Order of Good Templars is a gospel temperance group formed in the mid-19th century. A few years ago they realised that their name sounded a bit too religious/masonic so they changed it to Movendi. Their agenda of total abstinence remains the same. It is now an official partner of the WHO.

Øystein Bakke, Global Alcohol Policy Alliance and FORUT

The Global Alcohol Policy Alliance is another temperance group set up by Derek Rutherford. Notice the trend of temperance groups giving themselves bland names so they can slot themselves into the field of ‘public health’. Formed in 2000, Derek Rutherford said its priority was to “make the most of the opportunities provided by the development of the WHO Global Alcohol Strategy and the focus on non-communicable diseases.” It is certainly doing that.

Adam Knobel, Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education (FARE)

FARE is a state-funded anti-alcohol organisation set up by the Australian government with a $115 million grant. It says that it spends 50 per cent of its income on ‘policy and advocacy’ and 15 per cent on ‘leading change’. In other words, it is a pressure group.

Nason Maani, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

Maani is an activist-academic who has co-authored many hilariously bad articles with Mark Petticrew about the alcohol industry.

David Jernigan, Boston University School of Public Health

Jernigan is also on the board of the Global Alcohol Policy Alliance and speaks at their mad conferences.

Finally, there is Juan Tello. Listed as co-editor of the guide for journalists, he is in charge of the WHO’s Less Alcohol Unit. He recently gave an interview in which he complained about the ‘normalisation’ of alcohol and wibbled on about the ‘commercial determinants of health’. He makes no secret of ‘pursuing a no alcohol environment’.

His interview did contain one bit of good news, however.

Juan Tello: We give countries five recommendations that are cost effective to implement, especially in middle-income countries: increase pricing, particularly through taxation; ban marketing and sponsorships advertising alcohol; decrease the physical availability of alcohol outlets; enforce checks and control of blood alcohol concentration; and treatment. We are well positioned to do this when countries are willing to move forward.

Think Global Health: What’s the level of interest from countries?

Juan Tello: The uptake is low. It’s truly low.

Excellent. Let’s hope it stays that way. In the meantime, if journalists are looking for a story about alcohol, may I suggest an article about WHO reports being written by anti-alcohol activists?

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are only moderated after 14 days.