At Spiked, I started and ended the year by talking about how useless the COVID-19 models were. Having got that of my chest, it is now time for peace and reconciliation. Incredibly, some people were still calling for more restrictions as late as April 2022. They just couldn't let it go.

If you wanted to follow the evidence on smoking and COVID-19, this blog was almost the only place to go. I stopped counting studies when I got to 100. The great majority found smokers to be less likely to be infected, but when I discussed this at Spiked, I got the Facebook red flag treatment again.

In January, more evidence emerged of vaping's extraordinary ability to get smokers off cigarettes even when they don't want to quit. This was followed by a compelling Cochrane Review later in the year. Australians, however, were drip-fed a diet of lies about e-cigarettes in a country where the tobacco black market has grown to an absurd extent, and the Netherlands decided it wasn't even able to tolerate something as harmless as nicotine pouches. One Aussie doctor became so misinformed he started giving his son cigarettes to wean him off the vapes!

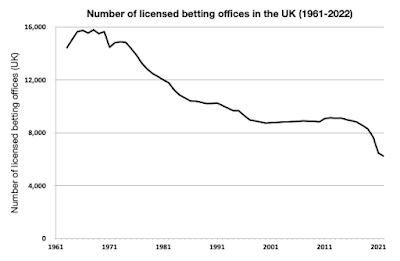

Gamblers, the gambling industry and their foes awaited a White Paper that was never published. The anti-gambling coalition, which wrongly presented the issue as one of public health, touted a claim about the number of gambling-related suicides which Public Health England had made up in its last days. It didn't stack up. In November, the Times also made a claim about problem gambling that was obviously untrue.

With regards to tobacco, fifteen years after the smoking ban began and a decade after I stopped smoking, I still thought it was a terrible mistake. I also argued that Theresa May should have consulted smokers before she promised that most of them would quit by 2030. Some of the ideas put forward by a member of the Blob to achieve this target were frankly insane.

On food, the government struggled to cope with the commitments made by a delirious Boris Johnson in 2020. A ban on placing tasty food in prominent positions in supermarkets came into effect in October (predictably, nanny statists immediately complained about imaginary 'loopholes'), but bans on BOGOFs and advertising were pushed back to 2023 and 2024 respectively. Unpopular though they were, the Conservatives could see that charging people more for food wasn't the smartest thing to during an inflation-driven cost of living crisis. Meanwhile, the Mayor of London made ridiculous claims about his ban on junk food advertising.

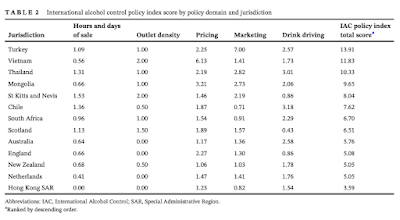

By July, the evidence that minimum pricing had died on its arse in Scotland had become overwhelming. Expect much high jinx when the SNP is required to prove it worked to bypass the sunset clause next year. And expect more junk science about alcohol advertising now that it is in the cross-hairs of the Scottish Government.

In crank's corner, George Monbiot was hoist by his own 'who funds you?' petard and James O'Brien worked on yet another conspiracy theory for his listeners at LBC. Aseem Malhotra continued his downward spiral and anti-vaxxers wilfully misunderstood every piece of Covid data.

In the summer, I wrote a series of columns for the Times in which I discussed the perils of low interest rates, the risks of hiking corporation tax and why the energy price guarantee should be means tested. To no avail, clearly.

It was a busy year in politics with three Prime Ministers and goodness knows how many Chancellors. Liz Truss's brief tenure was a disaster for the Conservative Party and, briefly, for the pound, but the economy was broken before she got her hands on it and it is a myth that Trussonomics cost the country £30 billion. When Rishi Sunak took over, Jeremy Hunt preached austerity while borrowing like there was no tomorrow and doing nothing about inflation.

On a happier note, my pal Ronnie O'Sullivan won his seventh snooker World Championship and I wrote about how lucky we are to share a planet with him. I also reviewed the deluxe edition of the Beatles' Revolver and the solo career of Paul McCartney. On a less happy note, I reviewed a documentary about Russia (1985-1999).

I also reviewed some excellent books about The New Puritans and interest rates, plus a contrarian take on Prohibition.

And I interviewed lots of people for The Swift Half with Snowdon. Some of the most interesting discussions were with some of the less well known people, including Angela Knight (on energy), David Zaruk (on anti-science NGOs), Bill Hanage (on Covid), Marewa Glover (New Zealand authoritarianism) and Edward Chancellor (interest rates).

Thanks for all your comments, shares and visits in 2022. Have a great New Year's Eve and I'll see you on the other side.