The plan to ban buy-one-get-one-free (BOGOF) and 3 for 2 deals on so-called junk food just as the cost-of-living crisis peaks in the autumn increasingly looks like an act of political self-immolation. The idea was championed by Public Health England which was closed down for being incompetent and, as Jeremy Driver says, it was a classic example of "luxury politics, divorced from the material concerns of citizens".

There is also evidence that during the high inflationary period of 2008-2010,

promotions were a useful coping strategy for shoppers to manage the worst effects

of food and drink inflation.

Inflation briefly hit 5% in that period. It currently exceeds 6% and is expected to exceed 8% by October when the ban is due to begin.

The thinking seems to have been that it was OK to remove the "coping strategy" of price promotions so long as inflation was low. Well, it ain't low any more.

During this period as food and drink became relatively

more expensive, behavioural data shows that many shoppers increasingly selected

items offered on promotion to help them save money.

You don't say!

Promotions at this level do of course play a role in helping shoppers reduce the

cost of the items that they choose to buy. Based on the breadth and depth of

promotions we can calculate a “giveaway” figure which equates to a 16% or

approximately £634 reduction on a typical household’s annual, take home food and

drink bill. In other words if people bought the same quantity of food and drink with

no promotions they would need to spend an additional £634 for the same items.

The actual cost of the policy is likely to be less than £634 per household because retailers have other ways of discounting prices, but multibuy deals save consumers money, in part, because they save retailers money and allow them to adopt the Pile 'Em High approach. Retailers get bigger discounts from wholesalers when they place bigger orders and multibuy deals also help them clear surplus stock. They are an engine of efficiency.

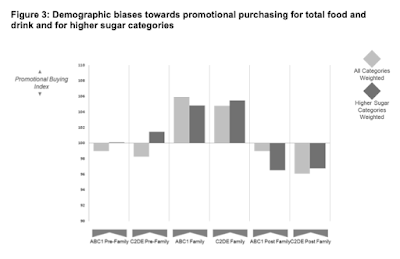

These deals particularly benefit families because families buy more food. Sure enough, families are more likely to take advantage of them.

The PHE report goes on to claim that these deals actually cost consumers money because they end up buying more products but their analysis is shaky and they don't seem to consider the possibility that people might want to buy more food. Or indeed need to.

The bottom line is that the ban was intended to make people buy less food by making it more expensive. Like minimum pricing, it is the cousin of the sin tax but unlike a sin tax it doesn't raise any money for the government. That means the government can abandon the idea at zero cost and save consumers money.

Surely this is a no-brainer?

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are only moderated after 14 days.