James O’Brien, LBC’s pied piper of mid-wits, told his listeners on 22 April that ‘646 people died yesterday’ of Covid-19. He acknowledged that official statistics showed that the infection rate was falling, but muttered conspiratorially that he was ‘a little bit confused about how we’re keeping a proper handle on the number of infections now given that most of us have stopped testing’.

If even Mr O’Brien, whose books include How To Be Right and How Not To Be Wrong, is still confused by Covid statistics after two years, what hope is there for those us who didn’t attend a top public school? Sure enough, Twitter was awash with people repeating the 646 deaths figure and rebutting claims about falling infection rates with the words ‘we’re not testing’.

Anyone with an internet connection and mild curiosity knows this to be nonsense. The number of people in the UK who have died with Covid-19 written on their death certificate has not exceeded 200 a day since January 2022 and has not exceeded 300 a day since February 2021. Under the alternative measure of ‘deaths within 28 days of a positive test’, the figure has only exceeded 300 twice in the last year, but that metric has become increasingly misleading since the highly infectious Omicron variant became dominant.

Even the death certificate figures overstate the scale of the problem. In previous waves, Covid-19 was the underlying cause of around 90 per cent of deaths when the disease was listed on the death certificate. In recent weeks it has fallen below 65 per cent.

There were not 646 Covid-related deaths on 21 April, nor anything close to it. Instead, there was a backlog of reported deaths following a bank holiday weekend. No deaths were reported on Good Friday, Saturday, Easter Sunday or Monday. If you still haven’t got the hang of this after all this time, you should probably keep your opinions to yourself.

Saturday, 30 April 2022

Saying farewell to Covid again

Thursday, 28 April 2022

Pod chats

Wednesday, 27 April 2022

Kellogg's sues the government

|

| 'Junk food' |

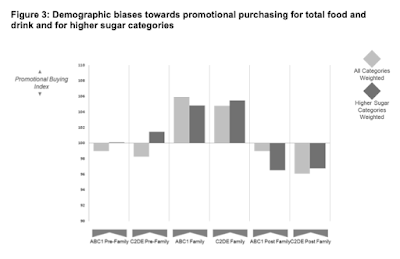

Food giant Kellogg's is taking the government to court over new rules that would prevent some cereals being prominently displayed in stores because of their high sugar content.

In a statement, Kellogg's said it had "tried to have a reasonable conversation with government" over the issue without success...

... hence their legal challenge.

Chris Silcock, Kellogg's UK Managing Director, said: "We believe the formula being used by the government to measure the nutritional value of breakfast cereals is wrong and not implemented legally. It measures cereals dry when they are almost always eaten with milk.

"All of this matters because, unless you take account of the nutritional elements added when cereal is eaten with milk, the full nutritional value of the meal is not measured."

Popular brands such as Crunchy Nut Corn Flakes and Fruit and Fibre are classified as foods that are high in fat, sugar or salt in their dry form and so retailers may be prevented from displaying such products in prominent positions, harming sales.

Caroline Cerny, from the Obesity Health Alliance, said: "This is a blatant attempt by a multinational food company to wriggle out of vital new regulations that will limit their ability to profit from marketing their unhealthy products.

"It's shocking that a company like Kellogg's would sue the government over its plans to help people be healthier rather than investing in removing sugar from their cereals."

A Department of Health and Social Care spokesperson said: "Breakfast cereals contribute 7% - a significant amount - to the average daily free sugar intakes of children.

"Restricting the promotion and advertising of less healthy foods is an important part of the cross-government strategy to halve childhood obesity by 2030..."

Monday, 25 April 2022

An innovation principle for new nicotine products

Sunday, 24 April 2022

Mexico was meant to prove a sugar tax worked. New figures tell a different story

Back in January we were told that Mexico’s tax on sugary drinks cut consumption by six per cent in its first year. This received global news attention at the time because it was seen as proof that sugar taxes ‘work’. Such taxes really only work if they reduce obesity, of course, but given the virtually non-existent impact of previous soft drink taxes, campaigners could be forgiven for their excitement about some empirical evidence finally coming their way.

The figure came from a study in the British Medical Journal conducted by one of the world’s most prominent sugar tax campaigners, Barry Popkin, which modelled soft drink sales against a theoretical counterfactual, which is to say it compared sales after the tax with what the authors thought would have happened if the tax had not been enacted. There is always a degree of ‘garbage in, garbage out’ with economic forecasting (which is essentially what this is, albeit retrospectively), but the results did not strike me as unrealistic at the time. Standard economic theory suggests that higher prices lead to lower demand.

It seemed to me that the problem with Mexico’s soda tax was not that it didn’t reduce consumption, but that it reduced it by a trivial amount at a significant cost to consumers. Here was a relatively poor country introducing quite a large tax on a fairly small component of the country’s calorie supply and making a little dent in it. At best, the BMJ study suggested that it had reduced calorie consumption by the equivalent of one sugar cube a day which, as Tom Sanders said at the time, is ‘a drop in the caloric ocean’.

In recent months there have been reports of sugary drink sales in Mexico bouncing back and some have even claimed that sales never fell to begin with. Getting the actual data has been surprisingly difficult up until now, but thanks to Mexico’s National Institute of Public Health (NIPH), we have it — and it tells a rather different story.

The tax was implemented in July 2014. According to the NIPH — which keenly supports the tax — annual sales of sugary drinks averaged 18.2 million litres between 2007 and 2013. In 2014, this rose to 19.4 billion litres, and it rose again in 2015 to 19.5 billion litres.

On the face of it, sugary drink sales were seven per cent higher last year than they were before the tax was introduced. This is not good news for Jamie Oliver, but these figures need to be adjusted for population growth. Using the correct measure of per capita consumption we get the following results:

2007-13: 160 litresThis is still not good news for Jamie Oliver and so the NIPH asks the public to trust regression models that have made further adjustments to the data for possible confounding variables such as climate and economic growth. As with the BMJ study, these models suggest that soft drink consumption would have been higher if there had been no tax. Perhaps it would, but there is clearly a difference between arguing that sales would have been higher if the weather had been colder or the economy had been sluggish and asserting, as the NIPH does, that ‘there was an average decrease of -6% in 2014 and -8% in 2015’.

2014: 162 litres

2015: 161 litres

They conclude:

Without these adjustments, the (erroneous) conclusion would be that there was an increase in sales after the tax, both in 2014 and in 2015, while the adjusted analysis shows that there was a reduction in sales after the tax.

At this point, words are beginning to lose their meaning. It is rather like the supporter of a losing football team claiming they would have won if their striker hadn’t been sent off with ten minutes to go. It could be true, but no one will ever know. The fact remains that they lost, and while you might be sympathetic to a supporter who claimed they should have won, you would worry about their state of mind if they claimed — as matter of historical fact — that they did win.

Imagine the hilarity at the Mexican tax office if Coca-Cola and Pepsi-Co requested only paying tax on what public health campaigners said they sold in 2015 rather than on what they actually sold. If they told the government that their recorded sales figures were ‘erroneous’ on the basis of a speculative regression model I suspect they would be met with a terse reply.

Modelling of this sort has its place, but we are in danger of replacing fact with theory. The appeal of the Mexican sugar tax as a global precedent is that it led to a reduction in sugary drink consumption and therefore, it is supposed, a reduction in calorie intake. Claiming that it led to a six per cent reduction in fizzy drink consumption is an unambiguous normative statement that has been repeated around the world.

We now know that statement would be more truthfully phrased as ‘consumption rose by one per cent after the tax was introduced but some researchers have hypothesised that it would have fallen by six per cent if x, y and z had occurred’. We also now know that there is no chance of the tax reducing obesity because, whatever the models might say, the empirical fact is that Mexicans are drinking more sugary drinks than they did before.

Tuesday, 12 April 2022

Graphic warnings on alcohol

Prominent health warnings on alcohol products make drinking “unappealing”, new study findsYoung adult drinkers are more likely to perceive alcohol products as “unappealing” and “socially unacceptable” if they display prominent health warnings, according to new research.

Each warning set included one general (‘Alcohol damages your health’) and two specific (‘Alcohol causes liver disease’, ‘Alcohol causes mouth cancer’) warnings. The specific warnings were selected as more than three-quarters of alcohol-specific deaths in the UK in 2020 were caused by alcoholic liver disease and past research suggests that it is more effective to specify the type of cancer, with alcohol-related mouth cancer prevalent in the UK.

For those in the pictorial warning condition, an appropriate image was chosen to reflect each warning: ‘Alcohol damages your health’ (image of blood pressure test); ‘Alcohol causes liver disease’ (image of person clutching their liver); ‘Alcohol causes mouth cancer’ (image of CT scanner in a hospital). For consistency, in each condition participants were shown an image of a bottle of Smirnoff Red Label No. 21 vodka.

After controlling for covariates, participants who viewed products with warnings were significantly more likely to perceive the products as unappealing and socially unacceptable than the control condition.

Sunday, 10 April 2022

Escaping Paternalism with Glen Whitman

It was my great pleasure to speak to one of my favourite economists, Glen Whitman, this week about nudge theory. His book Escaping Paternalism, which he wrote with Mario Rizzo, is a must read.

Friday, 8 April 2022

Anti-gambling fanatic asks government to ignore the facts

It seems that the removal of sponsorship would not unduly harm Premier League clubs, but it would very probably have a serious effect on smaller clubs; some of those in the EFL might go out of business without this sponsorship if they cannot find alternatives. This would be highly regrettable, especially given the close link between some of these clubs and their local communities. The financial situation of some of them is currently particularly fragile because of the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on sport.

We therefore think they should be given time, perhaps three years, to adapt to the new situation. They would not be allowed in that time to enter into new sponsorship contracts with gambling companies, but any existing contracts could continue until they terminate, and clubs would have time to seek alternative sources of sponsorship.

The committee did not cite a single piece of evidence to justify a ban on gambling sponsorship. They just decided that there was too much of it.

It is generally assumed that the increase in advertising is one of the causes, perhaps the main cause, of gambling-related harms. There is certainly a correlation, but we have received no evidence nor been pointed to any research which proves that there is any causal link between gambling advertising and problem gambling. On the contrary, Mr Parker [CEO of the Advertising standards Authority] said: “The indicators do not accord with the view that the undoubted increase in gambling advertising and in accessibility to gambling services, through smartphones, is driving a significant increase in problem gambling.

Mr Parker added: “I worry about this, because it seems common-sensical that, if there is a big increase in the volume of advertising, all other things being equal, it ought to lead to an increase in problems. The data is not showing that ...” This concerns us too. Plainly the companies would not spend increasingly large sums on advertising if they did not believe that this would increase either the overall amount gambled, or the amount gambled with their company, or both, and it does indeed seem counter-intuitive that this should not also result in an increase in gambling-related harms.

'Flawed' EFL gambling evidence should be ignored - MP"Flawed" evidence submitted to the government's gambling review by the English Football League should be ignored, according to an MP who chairs a parliamentary group for gambling reform... Labour MP and chair of the All Party Group for Gambling Related Harm Carolyn Harris said gambling minister Chris Philp should "choose to ignore" the research in the gambling review, for which a white paper is due to be published within weeks.

The EFL, which is sponsored by Sky Bet and whose clubs receive £40m a year from gambling companies, commissioned research, seen by the BBC, which said there was "no evidence" that sponsorship influences participation in betting.

It also said that gambling participation in sport "had remained flat at about 9% of the population between 2010 and 2018" and over the same period "the rate of problem gambling in sports had halved from 6% to 3%".

Vita's critique, which was commissioned by campaign group Clean Up Gambling, said the research was "faulty" based on using two different types of survey to assess gambling participation and problem gambling rates.

One of those surveys, conducted by the NHS and which runs from 2012 to 2018, cautioned against combining its results from a previous version of the survey because different methods were used to collect data.

The EFL's research also said there was "no evidence that sponsorship of clubs or leagues by betting operators influences participation in betting, or being a Skybet customer".

But the influence to gamble or not was based only on fans whose team had a gambling sponsor on their shirts and whether their team played in the Sky Bet-sponsored EFL, disregarding any other sponsorship or advertising in football as a whole.

It also concluded that "not being a fan of football decreases the probability of being a bettor, and of being a Skybet customer".

Harris told The Sports Desk podcast: "A decent thing would be to withdraw [the EFL] evidence, but they're not going to do that. So you need to take it with a massive pinch of salt which I suspect [the government] do.

"[The minister] can ignore it, he can choose to ignore it or discard it. And I would like to think that he would, but we know he's overwhelmed with evidence at the moment. I don't think the gambling minister is entirely hoodwinked. I think he sees a lot of the content for his white paper as being flawed."

Wednesday, 6 April 2022

So many awkward studies about smoking and COVID-19

If you check out my list of COVID-19/smoking studies you'll find more than 70 epidemiological studies looking at how smokers fare when faced with the virus. In short, the evidence overwhelmingly shows that they are much less likely to get infected.

Almost the only exceptions are a handful of Mendelian Randomisation studies that can't distinguish between smokers and nonsmokers and instead assume that people with genes that are associated with a propensity to smoke are smokers. For various reasons, that is not a sound assumption after decades of anti-smoking education and legislation. When it comes to lifestyle risk factors, the blunt tools of MR are only any good if you don't want to find an association.

Current smoking was associated with lower adjusted rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection (aHR=0.64 95%CI:0.61-0.67), COVID-19-related hospitalization (aHR=0.48 95%CI:0.40-0.58), ICU admission (aHR=0.62 95%CI:0.42-0.87), and death (aHR=0.52 95%CI:0.27-0.89) than never-smoking.

In what has been termed the “smoker’s paradox,” studies across the globe have generally found lower risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection for current versus never smoking, an inverse association between smoking prevalence and the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection, and a lower than expected prevalence of current smoking among patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

... A national matched case-control study from Korea found that current (OR=0.33, 95%CI:0.28-0.38) and former smoking (OR=0.81, 95%CI:0.72-0.91) was associated with a lower odds of SARS- CoV-2 infection than never-smoking. Data from 38 European countries found that after covariate adjustment, smoking prevalence was inversely related to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Further evidence comes from a cohort study of an aircraft carrier crew exposed to SARS-CoV-2 while at sea. Current smoking was associated with a lower odds of SARS-CoV-2 infection (OR=0.64, 95%CI:0.49-0.84), with even lower odds for those smoking more heavily...

That was a particularly amusing finding and an interesting study.

Many researchers who find that smokers are at less risk of Covid are keen to downplay their findings. They sometimes ignore them in the text altogether But the authors of the Californian study seem more interested in testing the various explanations that have been put forward and their study does this rather well.

Our study has important strengths. First, it is now recognized that non-representative sampling (e.g., hospitalized patients, people tested for active infection, voluntary participants) in many observational studies of risk factors for COVID-19 can lead to collider bias distorting true associations between risk factors and outcomes. A unique strength of our study is the inclusion of a large defined cohort of patients at-risk for COVID-19 within a closed healthcare system followed from testing and infection to death.

Since all patients were insured, results are unlikely due to variations in access to care.

Our retrospective cohort study design properly estimates risk over time, making it more rigorous than convenience sample studies.

Further, the semi-parametric Cox proportional hazards model flexibly allows the underlying baseline risk to vary over the study period, accounting for changes in risk/exposure as the pandemic unfolded. By assessing smoking status during standard care pre-pandemic, our smoking data do not reflect short-term changes resulting from infection (e.g., if smokers with severe COVID-19 consequently quit smoking and report former smoking status). The small percentage missing smoking status was excluded rather than included with never-smoking, reducing the likelihood of misclassification.

Prior studies have speculated that people who smoke may be more likely to get tested for COVID-19 when asymptomatic (e.g., due to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] guidance characterizing them as at-risk) or due to smoking-related symptoms mimicking COVID-19 symptomatology (e.g., cough), increasing their percentage of negative tests. While we are unable to directly test this, it is reassuring that in our study, COVID testing prevalence was comparable by patient smoking status (24.7% current, 28.1% former, and 24.6% never- smoking) and with a similar number of tests, on average.

Understanding whether smoking is associated with risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 severity is critical for informing public health strategies to mitigate risk during future outbreaks and prioritize at-risk groups for vaccination outreach, boosters, and treatments as they become available.

Tuesday, 5 April 2022

The sorry state of vaping research

Dozens of new studies about vaping are published every week and most of them are absolutely dismal. They start from a false premise, use biased terminology, treat 'EVALI' as if it was caused by conventional vaping, fail to distinguish the effect of vaping from the effect of prior smoking, treat correlation as causation, and employ poor methodologies to come up with a desired anti-vaping conclusion.

A new study titled 'Analysis of common methodological flaws in the highest cited e-cigarette epidemiology research' shows just what a sorry state the field is in, particularly the garbage that gets the most citations and is most attractive to journalists.

Our critical appraisal reveals common, preventable flaws, the identification of which may provide guidance to researchers, reviewers, scientific editor, journalists, and policy makers. One striking result of the review is that a large portion of the high-ranking papers came out of US-dominated research institutions whose funders are unsupportive of a tobacco harm reduction agenda.

However, this does not mean there is a trove of good research out there that answers the big questions, but merely did not make the popularity cut. There is not. Notably, papers discussing the effect of vaping on smoking initiation shared common flaws. By contrast, papers addressing the effect of vaping on smoking cessation or reduction demonstrated a broader variety of flaws, yet common themes emerged. Our analysis of common flaws and limitations may guide future researchers to conduct more robust studies and, concomitantly, produce more reliable literature. There are countless sources of good building-block information that can be pieced together to provide knowledge. To provide useful information, research questions should be precise, contingent, nuanced and focused on quantifications that are motivated by externally defined questions. Such research necessitates proactive design, rather than utilizing already existing, but not fit-for-purpose, datasets.

Friday, 1 April 2022

Boris's BOGOF rip-off

The plan to ban buy-one-get-one-free (BOGOF) and 3 for 2 deals on so-called junk food just as the cost-of-living crisis peaks in the autumn increasingly looks like an act of political self-immolation. The idea was championed by Public Health England which was closed down for being incompetent and, as Jeremy Driver says, it was a classic example of "luxury politics, divorced from the material concerns of citizens".

There is also evidence that during the high inflationary period of 2008-2010, promotions were a useful coping strategy for shoppers to manage the worst effects of food and drink inflation.

During this period as food and drink became relatively more expensive, behavioural data shows that many shoppers increasingly selected items offered on promotion to help them save money.

Promotions at this level do of course play a role in helping shoppers reduce the cost of the items that they choose to buy. Based on the breadth and depth of promotions we can calculate a “giveaway” figure which equates to a 16% or approximately £634 reduction on a typical household’s annual, take home food and drink bill. In other words if people bought the same quantity of food and drink with no promotions they would need to spend an additional £634 for the same items.