Doctors prescribe drugs to tackle Britain’s gambling epidemic’ was the top story on the Times‘s front page on Wednesday. ‘The growing toll of problem gambling in Britain,’ it said, ‘is now so serious that the NHS has started prescribing £10,000-a-year drugs for some of the worst addicts.’ The Times echoed calls from the Campaign for Fairer Gambling for a ‘crackdown on fixed-odds betting terminals (FOBTs), which have been dubbed the “crack cocaine” of gambling’.

There are several problems with this story. A few years ago, I dug into the claim that FOBTs were the ‘crack cocaine of gambling’ and found that virtually every form of gambling has been given this tag at one time or another. I tracked it back to Donald Trump in the 1980s who used it to describe a video bingo game called Keno which he saw as a threat to his casino business. Since then it has been used to attack video lottery terminals, slot machines, pokies, horse racing, lotteries, casinos, internet gaming and scratchcards.

When my research was published I had the vague hope that people would think twice before parroting the ‘crack cocaine’ claim about FOBTs in the future, but that was clearly in vain. Three years later, it is seemingly impossible for any newspaper to write about these machines without including this evidence-free metaphor.

Secondly, there is precious little evidence that there is a ‘growing toll of problem gambling in Britain’. The British Gambling Prevalence Survey is by far the most thorough body of research in this area. Sadly now disbanded, it produced three reports using two separate methodologies to measure problem gambling between 1999 and 2010. Under one methodology, it found that gambling prevalence was 0.6 per cent in 1999, 0.6 per cent in 2007 and 0.9 per cent in 2010. Under the other methodology, it found prevalence rates of 0.8 per cent in 1999, 0.5 per cent in 2007 and 0.7 per cent in 2010. This suggests little, if any, change in the first decade of this century despite the introduction of FOBTs and the liberalisation of much of the gambling industry.

The British Gambling Prevalence Survey has since been replaced by Health Surveys for England and Scotland. The latest English report, published in 2013, found a problem gambling prevalence of 0.5 per cent under one methodology and 0.4 per cent under the other. The latest Scottish report found a prevalence rate of 0.5 per cent under both measures. If there is an ‘epidemic’ of problem gambling, it has been missed by every reputable survey.

The Times ignores the latest prevalence studies and instead claims that there are 562,000 problem gamblers in Britain. This is based on the fact that ‘the last gambling prevalence survey in 2010 found there were 450,000 problem gamblers in the Britain [sic] but experts at GamCare say the number of addicts is likely to grow in proportion to the size of the industry’.

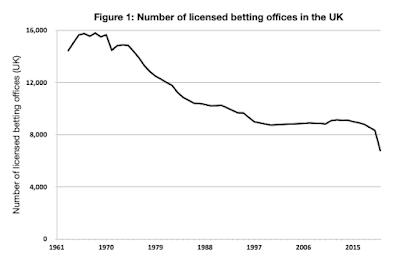

Leaving aside the dubious assumption behind this factoid, the industry is not growing. After adjusting for inflation, the British gambling sector has a lower Gross Gambling Yield (which essentially means revenue) than it did in 2008. Contrary to popular belief, the number of bookmakers has been falling i the long term and has expanded only fractionally in the short term. The number of bookies peaked in 1968 at 15,782 before falling to an all-time low of 8,732 in 2000. It has risen only very slightly in the years since. At the last count, there were 8,819 bookies in the UK, representing a one per cent rise on the fin de siècle nadir, significantly less than population growth and a far cry from the ‘dramatic proliferation’ claimed by opponents of gambling.

As for the situation getting so bad that the NHS is having to dish out drugs at a cost of £10,000 per person, the prescriptions (for naltrexone) are being handed out by the National Problem Gambling Clinic, a private organisation which is mainly funded by the Responsible Gambling Trust (which, in turn, is entirely funded by the gambling industry). According to the Responsible Gambling Trust, the drug does not cost £10,000 a year. It costs £68 for three months. When I asked them about it, they told me that the clinic has only prescribed it five times since April 2015.

These are not minor discrepancies. There is a world of difference between the publicly funded NHS dishing out £10,000-a-year drugs to the countless victims of Britain’s gambling epidemic and a predominantly privately funded clinic prescribing £272-a-year drugs to five people against a backdrop of problem gambling rates that have barely fluctuated since 1999. But when have facts ever got in the way of a moral panic?

UPDATE

Since this article was written the rate of problem gambling has remained at 0.5-0.7%. It has not fallen since fixed odds betting terminals were effectively banned. See A Safer Bet. The number of bookies has, however, collapsed to 6,735 and thousands of people have lost their jobs.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are only moderated after 14 days.