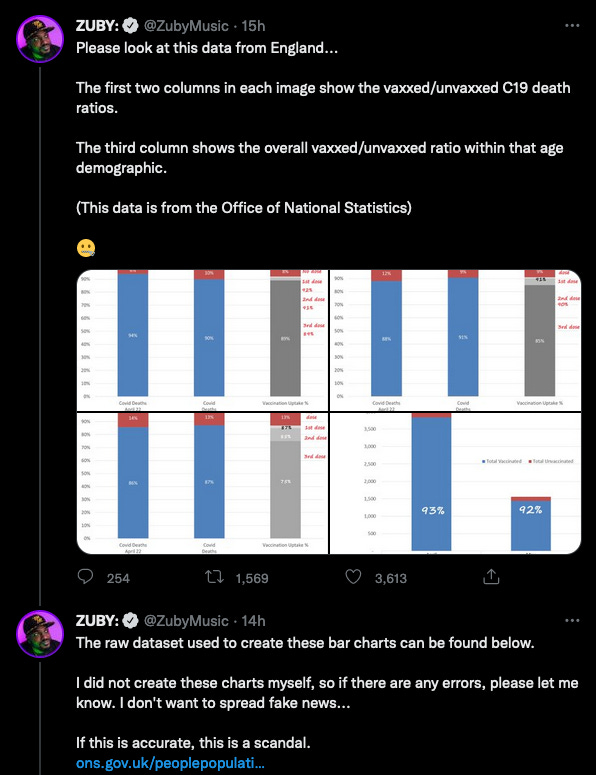

The latest ONS data show that 93% of Covid deaths in April and May were of vaccinated people, in a population that is 93% vaccinated, suggesting zero protection. The same is true in each age group. https://t.co/6uNQmMsLB9

— Toby Young (@toadmeister) July 27, 2022

In his defence, he posted a link to the relevant ONS spreadsheet and asked people to put him straight if he had misunderstood. He doesn’t want to spread fake news, you see?

It is a pretty hollow defence because numerous people have explained why he is wrong and yet, at the time of writing, he still hasn’t deleted his tweet.

Throughout the pandemic, smileys and anti-vaxxers have been blissfully ignorant of the base rate fallacy. Insofar as a few of them are aware of it, they don’t think they have fallen into it on this occasion. They note that 93% of the British population have been vaccinated and, since a similar proportion of Covid-related deaths are among the vaccinated, this strikes them as the final proof that the jabs don’t work.

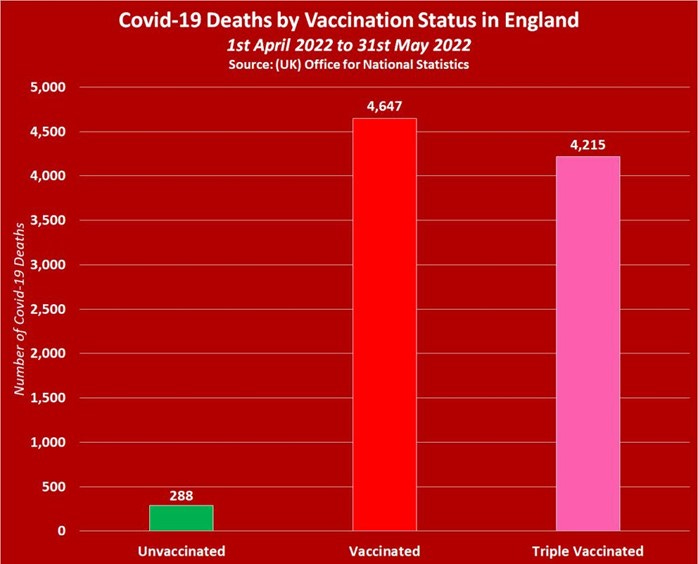

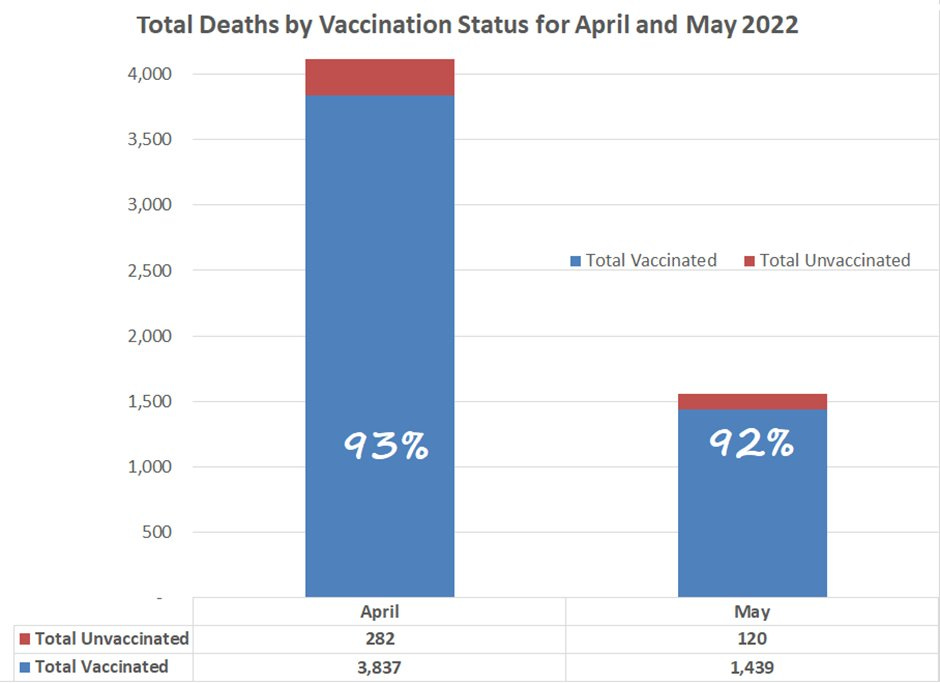

Their raw figures are broadly correct. If you go to Table 1 of the spreadsheet, you can see all the Covid-related deaths each month by vaccination status. And if you go to the effort of tallying them all up, in April 2022 there were 3,571 deaths of which 206 were among unvaccinated people. In May 2022, there were 1,364 deaths, of which 82 were among the unvaccinated (NB. the numbers are based on death certificates so the figure for May will rise once all the deaths have been registered).

The overwhelming number of deaths were indeed among people who had had at least one vaccine: 94% in April and 94% in May. (Zuby’s chart has slightly different figures for some reason, but the general picture is similar.)

Add these figures together and you get 4,935 deaths for April and May combined, of which 288 were among the unvaccinated. These are exactly the figures shown in the red graph above. 94% again.

As the ONS’s Sarah Caul and others have pointed out, none of this tells you very much unless you adjust for the age and characteristics of the people who died. If you look at the age-standardised mortality rates, the picture is rather different.

In April, the age-standardised rate for Covid-related mortality was 204.7 per 100,000 person-years among the unvaccinated and 96.5 per 100,000 among the ever-vaccinated.

In May, the age-standardised mortality rate for Covid-related death was 77.6 per 100,000 among the unvaccinated and 35.5 per 100,000 among the ever-vaccinated.

In other words, people who have been vaccinated are half as likely to die a Covid-related death as those who ‘trust their immune system’.

I won’t go over the base rate fallacy again. Plenty of people have explained it before and those who don’t want to hear it - or can’t understand it - will never be persuaded by me. But it is worth noting that you really have to go out of your way to arrange the figures in the manner shown in the graphs above. You have to add up a whole bunch of numbers, work out the percentages and plot them on a graph. Why go to such trouble when the age-standardised figures are right there in Table 1 next to numbers you’re adding together?

However, in the spirit of genuine sceptical enquiry, it is reasonable to ask why the vaccines only seem to be halving the risk of death when the original trials showed that they reduced the risk by over 90%. Funnily enough, the reasons involve issues with which smileys are very familiar. They just choose to ignore them on this occasion because they don’t fit their narrative.

The first is that the deaths listed in the ONS spreadsheet are what the ONS call ‘deaths involving COVID-19’ (which I call ‘Covid-related deaths’ above). These are deaths for which Covid is mentioned on the death certificate but for which Covid may not have been the primary cause. You may recall the whole ‘with Covid’’ versus ‘of Covid’ conversation in 2020-21. It was a virtual irrelevance back then because around 90% of deaths involving Covid had Covid listed as the primary cause on the death certificate.

But it is a much more significant issue now because the proportion of Covid-related deaths that are primarily caused by Covid has fallen. Since February 2022, the proportion of Covid-related deaths that the ONS classifies as ‘due to Covid’ has only been around 60-65%.

This means that at least a third of the deaths in the graphs above were mainly due to heart disease, cancer, dementia, etc. and Covid played little or no part. Since Covid vaccines do not prevent heart disease, cancer, dementia, etc., you wouldn’t expect a markedly higher survival rate among the vaccinated. Around a third of the deaths could not have been prevented with a Covid vaccine and they cannot therefore be used to gauge the efficacy of the vaccines. They only muddy the water.

It is extremely likely that if the ONS spreadsheet Zuby linked to confined itself to deaths due to Covid, rather than involving Covid, the age-standardised Covid mortality rate would be even lower among the vaccinated and higher among the unvaccinated.

Secondly, there is the issue of another smiley favourite: natural immunity. We were more than two years into the pandemic by April 2022 and the vast majority of people had already had Covid. The ONS estimates that between 27 April 2020 and 11 February 2022, 71% of people in England caught Covid at least once. Something in the region of 5% of the population caught it before 27 April 2020 and a very large number of people have had it since 11 February 2022.

A reasonable guess is that around 90% of the population have been infected at some point and the figure for unvaccinated people may be even higher.

Infection obviously produces a good deal of immunity and makes it likely that your next infection will be milder. If you survived Covid the first time, you’re very unlikely to die from it the second time.

By April 2022, virtually everybody in hospital with Covid had antibodies from vaccination or prior infection. That is why so few people are dying of Covid these days despite high rates of infection in the community.

There is also the small matter of lots of unvaccinated people already being dead by April 2022. They can only die once.

The clinical trials studied vaccinated people versus people who had not yet been infected - and they worked very well indeed. They work less well, relatively speaking, when you compare people who have antibodies from vaccination with people who have antibodies from prior infection. A combination of vaccines plus prior infection works best of all - that is why we still see better outcomes among vaccinated people relative to unvaccinated people - but the pool of unvaccinated people who have yet to be infected and die from it is inevitably running dry.

If Zuby, Toby, et al. want (further) proof the vaccine’s efficacy among people who have not been infected before, they need look no further than Table 1 again. If we check the figures for last April, the age-standardised Covid-related mortality rate was 146 per 100,000 among the unvaccinated but just 16 per 100,000 among the vaccinated.

In May 2021, the rate was 45.5 per 100,000 among the unvaccinated and a mere 6.2 per 100,000. Among those who had received a second dose, it was just 2.8 per 100,000.

All this stuff is right there on the same page of the same spreadsheet that the ‘sceptics’ have pored over to make their cute little graphs. How strange that they didn’t notice it.

.jpg)