January

The Lancet launchs the hilarious EAT-Lancet diet, a near-vegan regime promoted by two billionaires who spent much of the year jetting around the world to save the planet. This was followed by a rant about 'Big Food' in the same journal by people who literally want to regulate food like tobacco.

Meanwhile, the New York City health departments explicitly equates fizzy drinks with cigarettes and Tom Watson says that Coco Pops are the new tobacco.

The Fixed Odds Betting Terminals All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) becomes the Gambling Related Harm APPG and searches for new dragons to slay (so long as they don't involve the sectors of the gambling industry that are paying for it).

Philadelphia's soda tax, like all soda taxes, proves to be a flop.

Public Health England calls for a pudding tax because of course they do.

February

Politicians in Hawaii want to raise the smoking age to 100.

Fresh demands for plain packaging to be extended to food.

Banning fast food shops near school fails to work. Excuses abound.

Joy in heaven as one of the identikit, state-funded nanny state pressure groups gets defunded. The IEA publishes my latest report on the sock puppet phenomenon.

March

Woke food company Farmdrop amusingly falls victim to Transport for London's 'junk food' advertising ban.

On the tenth anniversary of The Spirit Level's publication, I look at how its hypothesis is standing up. Not well.

The government is intent on clamping down on 'junk food' without really knowing what it is.

Anti-smoking groups are still pretending that a levy on tobacco companies is anything other than yet another tax on smokers.

In a crowded field, Mark Petticrew was the year's number one junk social scientist. In March, he doubled down on his mad theory that the charity Drinkaware is downplaying the link between alcohol and breast cancer.

Steve Brine resigns as public health minister. The world shrugs.

The EU Health Commissioner wants medical regulation of e-cigarettes because of course he does.

Sugar taxes still haven't worked anywhere ever.

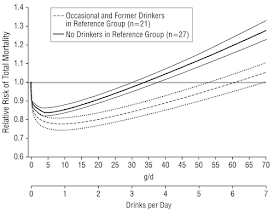

A dismal piece of quackademia tries to equate drinking with smoking.

|

| Dame Sally ended the year with another damehood |

As the new restrictions on fixed odds betting terminals come into effect, it is announced that 2,300 bookmakers will close. And it is still early days.

A respectable newspaper reports the insane claim that the smoking ban reduced heart disease mortality by two-thirds.

Tobacco prohibitionists try a new line: allowing the sale of cigarettes is an infringement of human rights or something. Nurse!

Scottish drinkers respond to minimum pricing by buying more alcohol from shops.

When the government introduces a bottle deposit scheme you'll wish you'd have heeded my warning.

America's ludicrous Truth Initiative loses the plot over e-cigarettes.

I reveal that Transport for London has spent thousands of pounds making its own adverts comply with its stupid food advertising restrictions.

The new Nanny State Index is published.

Norway's new health minister seems pretty cool.

Beverly Hills bans the sale of cigarettes, citing concerns about 'thirdhand smoke'.

Claims about the efficacy of the tobacco display ban fail to stack up.

Crazy unintended consequences in Australia's Northern Territory after minimum pricing is introduced.

The second anniversary of plain packaging passes without comment from anti-smoking groups for obvious reasons.

I nearly die laughing after Jamie Oliver's restaurant empire collapses.

June

The IPPR calls for plain packaging for food.

Panorama produces yet another one-sided programme about booze after Adrian Chiles is recruited by the temperance lobby.

The claim that alcohol consumption fell in Scotland after minimum pricing gets blanket coverage.

The news that alcohol-related deaths rose in Scotland after minimum pricing gets no coverage.

The British Medical Journal admits that the IEA is awesome.

I visit Canada with some MPs and Volte Face to see how cannabis legalisation is going (later discussed on this podcast).

Velvet Glove, Iron Fist (the book) turns ten.

July

Conservative leadership Boris Johnson says an extension of the sugar tax would 'clobber those who can least afford it' and calls for a review of sin taxes in general. An advocate of the sugar tax posted a rebuttal which doesn't stand up.

AG Barr announces a profit warning after reformulated Irn-Bru fails to fly off the shelves.

Estonia and Latvia slash alcohol taxes after getting kicked in the coffers by the Laffer Curve.

At the fag end of the Theresa May era, the government decides that the UK will be 'tobacco-free' by 2030. Smokers are not consulted.

Cowgirl junk scientist Anna Gilmore returns to remind us of her economic illiteracy.

I was on Triggernometry talking about the war on drugs, the nanny state, etc. and I debated Tory nanny statist Dolly Theis on the IEA podcast.

August

Josie Appleton reveals the full scale of the food reformulation folly.

As part of the war on their own obsolescence, anti-smoking campaigners call for health warnings on individual cigarettes.

'Public health' policies still don't save money.

September

Velvet Glove, Iron Fist (the blog) turns ten.

The usual suspects model the imagined effects of a snack tax and call it evidence.

In a report that was "kindly supported" by the Institute of Alcohol Studies (neé UK Temperance Alliance), the Social Market Foundation calls for a reform of Britain's alcohol duty system, but not in a good way.

The evidence that sugar taxes don't work keeps coming. Meanwhile, it transpires that the cash from the UK sugar levy has been swallowed into general government expenditure. Who could have seen that coming?

Public Health England admits that its policies won't reduce childhood obesity.

The American vaping panic - the year's most shameful episode - begins in earnest. It will be months before US agencies admit the truth.

The Royal Society of Public Health ignores the evidence and calls for a ban on fast food outlets in the vicinity of schools.

India bans e-cigarettes and tobacco stocks rally.

After ignoring the rise in alcohol-related deaths in Scotland in 2018, the media fall for some blatant cherry-picking to promote minimum pricing. Meanwhile, the Scottish government resorts to child exploitation as it moves to the next phase of its temperance agenda.

Public Health England's sugar reduction scheme proves to be a flop.

October

American 'public health' agencies hit new lows in their anti-vaping campaign.

There's no denying where you'll end up if you keep vaping. Take the first step to quit today visit: https://t.co/n9u0OdtGIm #ILQuitVaping pic.twitter.com/6QycNirIEC— IDPH (@IDPH) October 2, 2019

Former Chief Medical Officer Sally Davies calls for plain packaging for food. I bid farewell to her in this article.

Mark Petticrew returns again, this time claiming that Drinkaware is trying to get pregnant women to drink. Nurse!

A new study shows how badly hit pubs were by the smoking ban.

AG Barr release a new version of Irn-Bru which has even more sugar than the previous one.

Another Petticrew effort gets published, this time revealing his lack of understanding of advertising.

Are moderate drinkers responsible for the majority of alcohol-related harm?

November

The UK continues to have a low rate of problem gambling.

The Economist, of all publications, falls for the Institute of Alcohol Studies' economic illiteracy.

David Aaronovitch reckons Prohibition was a success. It wasn't.

Crazy laws against eating and smoking outdoors. Only in America?

The 'public health' gravy train rolls on, devouring taxpayers' cash as it goes.

Norway's sugar tax is good news for the Swedish economy.

December

The award for the year's worst reporting of a health story goes to the BBC.

Lancet authors don't take criticism of the preposterous EAT-Lancet diet well.

The Lancet shows that it will publish pretty much anything if it advances the editor's political agenda.

The hired guns of Sheffield's alcohol research group are hired by the Australian government to look at the drinking guidelines, with predictable results.

Junk science legend Stanton Glantz claims that a few years vaping causes diseases that require decades of smoking. It almost certainly doesn't.

Finally, I look back on a decade's 'public health' 'achievements'.

And don't forget you can still listen to every episode of the Last Orders podcast. This year our guests were Anthony Warner, Geoff Norcott, Andrew Doyle, Brendan O'Neill, Kate Andrews, Timandra Harkness, Julia Hartley-Brewer, Mark Littlewood, Martin Durkin, Toby Young, and Rob Lyons.