Tuesday, 30 April 2019

The Nanny State of the Nation

The 2019 edition of the Nanny State Index was published today. You can visit the website and download the full 84 page publication.

The Index, which I compile, is the most detailed record of over-regulation in the fields of alcohol, e-cigarettes, food, soft drinks and tobacco in the EU. It uses nearly a thousand pieces of data from 35 categories to produce a score out of 100 for each member state.

Regular readers won't be surprised to hear that Britain is one of the worst nanny states in Europe and the Index proves it. It has slipped from second place to fourth, but only because a flurry of anti-vaping and anti-alcohol activity in Estonia and Lithuania has led to those countries leapfrogging us in the table. It is certainly not because of any liberalisation in the UK where a tax on sugary drinks and plain packaging for tobacco has been added to sky-high sin taxes since the last edition was published.

To be fair, there has been precious little liberalisation anywhere else either. Nine EU countries now have taxes on sugary and/or artificially sweetened soft drinks. Eleven countries have taxes on e-cigarette fluid, and fifteen have a total or near-total ban on e-cigarette advertising. Twenty countries have some legal restrictions on e-cigarette use, including fourteen where vaping is banned wherever smoking is banned.

There has been less movement in tobacco policy since the upheaval of the EU Tobacco Products Directive (which came into full effect in May 2017). Every country except Germany has a total or near-total ban on tobacco advertising and most countries have extensive smoking bans. Even the traditionally smoker-friendly Czech Republic has capitulated to the tobacco control lobby, introducing a full smoking ban in May 2017.

The big temperance victories have come in Lithuania - where all alcohol advertising is now banned and you have to be be twenty years old to buy a drink - and in Scotland where minimum pricing was brought in last year. Wales is expected to introduce a 50p minimum price in the autumn and Ireland may follow suit next year. The Irish also have a package of tobacco-style anti-alcohol policies to be getting on with, including a retail display ban, an extensive advertising ban, and cancer warnings on bottles.

Whether it is food, drink, vaping or smoking, the lifestyle regulators have the wind in their sails. Consumers have had so few reasons to celebrate in the last two years that I can quickly list them all:

After introducing a tax on wine for the first time in 2016, Greece’s supreme administrative court declared it unlawful in September 2018. It was repealed the following January.

In March 2018, the new Austrian government cancelled its predecessors plans to introduce a smoking ban.

The Slovakian government recently legalised domestic distilling, albeit with strict regulations.

In November 2018, the Italian government slashed the tax on e-cigarette fluid from €0.38 per ml to €0.08 per ml, thereby cutting the price of an average bottle of vape juice by €3.

Also in November 2018, the Danish government froze tobacco duty and lowered duty on beer and wine.

These isolated examples represent the sum total of victories against the nanny state juggernaut since 2017. In Britain, the only sliver of good news is that we continue to lead Europe in our evidence-based approach to e-cigarettes. While many countries have gold-plated the EU’s anti-vaping laws by taxing e-cigarette fluid and banning e-cigarette advertising, organisations like Public Health England have actively encouraged smokers to switch to them. It is no coincidence that Britain now has the second lowest smoking rate in the EU.

You might assume, if you are slightly credulous, that the countries which embrace nanny state policies most enthusiastically have the best health outcomes. They don't. The war on fun is all pain and no gain. As the graphs below show, the countries which regulate tobacco more heavily do not have lower rates of smoking, those which regulate alcohol more heavily do not have lower rates of drinking, and those with the highest scores in the Nanny State Index overall do not have longer life expectancies.

So here we have a set of policies that restrict freedom and make us poorer while failing to achieve their stated objective. It would be nice to think that British politicians view the UK’s high ranking in the Nanny State Index as a source of national shame. Alas, I suspect that most of them will merely be disappointed that we have dropped out of the top three.

It is all rather depressing. Even the traditionally tolerant Dutch are in the process of putting a raft of paternalistic policies through parliament. Influential interest groups funded by billionaire activists, including the EAT campaign and Bloomberg Philanthropies, are pushing to introduce tobacco-style regulation of food and soft drinks. The Baltic States have been encouraged by the EU's Health Commissioner to tax sugar. In Ireland there is talk of following up 2018’s Public Health (Alcohol) Act with a similar law to tackle food. In Britain there is talk of a ‘pudding tax’ to go alongside the clamp down on so-called 'junk food'. We can also expect a growing clamour for a meat tax in the years ahead.

We can't even blame the European Union for it. The EU has some petty and counterproductive policies on tobacco and e-cigarettes, but it cannot be held responsible for regressive taxation, draconian smoking bans and excessive regulation of alcohol and food, nor for most of the nanny state laws that affect anything else. The gulf between the most liberal country at the bottom of the Index (Germany) and the most heavy-handed country at the top (Finland) shows how much latitude member states have. Treating your citizens like children is, by and large, a domestic policy choice. So far, it has been a choice that British politicians, whatever colour their rosette, have been happy to make.

You can read my article about this in the Telegraph here (£).

Monday, 29 April 2019

Moving the goalposts for minimum pricing

Scotland's public health minister, Joe Fitzpatrick, has written about minimum pricing as its first anniversary approaches...

The headline is untrue - or, at least, unproven - but, to be fair, he doesn't actually say that. He says:

Which doesn't mean very much.

The article is only of interest as an exercise in expectation management. Fitzpatrick is preparing the public for the news that alcohol consumption rose in the first year of minimum pricing, as now seems very likely:

Note how he is presenting a fall in alcohol consumption as a best case scenario - the icing on the cake if it happens. This is very different to the confident claims of a 3.5 per cent decline in the first year.

By presenting the policy as a way to slow down the growth in alcohol consumption, Fitzpatrick is moving the goalposts. He is also rewriting history. Alcohol consumption has not been growing. It is at a twenty year low.

In addition to lowering expectations of success, he is getting the Scottish public ready for the inevitable price rise - which the 'Liberal' Democrats are already demanding...

And then we get the usual stuff about there being no 'magic bullet'. It's the same thing we heard after the sugar levy began, after plain packaging began and after ever other ineffective nanny state policy takes effect...

No one thinks that there is one policy that will eradicate a complex problem, but, as with the sugar tax, we should be able to expect a noticeable improvement from a policy that costs us many millions of pounds. That doesn't seem to be happening and so the goalposts are being moved and all the grand promises are gradually being buried.

There was never any chance of minimum pricing being repealed. If it fails, its failure will be used as an excuse to raise the price and add a range of new taxes and bans to the mix.

A year after Scotland made history we are a healthier country

The headline is untrue - or, at least, unproven - but, to be fair, he doesn't actually say that. He says:

A year on, minimum pricing is setting a new benchmark in creating the healthier and fairer Scotland we all want to see.

Which doesn't mean very much.

The article is only of interest as an exercise in expectation management. Fitzpatrick is preparing the public for the news that alcohol consumption rose in the first year of minimum pricing, as now seems very likely:

In June, we will see the first meaningful analysis of sales which will tell us the short-term effect on the volume of units sold. After 5 years there will be an overarching expert evaluation of the impacts of minimum pricing, and whether it has slowed the growth in alcohol consumption, or even helped reduce consumption in the long-term.

Note how he is presenting a fall in alcohol consumption as a best case scenario - the icing on the cake if it happens. This is very different to the confident claims of a 3.5 per cent decline in the first year.

By presenting the policy as a way to slow down the growth in alcohol consumption, Fitzpatrick is moving the goalposts. He is also rewriting history. Alcohol consumption has not been growing. It is at a twenty year low.

In addition to lowering expectations of success, he is getting the Scottish public ready for the inevitable price rise - which the 'Liberal' Democrats are already demanding...

When we set the price at 50p we struck a balance between public health and social benefits, and intervention in the market. I believe it’s proportionate. This initiative is still in its infancy having been in place for just a year and as time goes on we’ll continue to keep the level it is set at under review to determine if an increase is necessary in the short-term.

And then we get the usual stuff about there being no 'magic bullet'. It's the same thing we heard after the sugar levy began, after plain packaging began and after ever other ineffective nanny state policy takes effect...

There is no magic bullet, no single action that will stop alcohol abuse. That’s why we’ve taken a range of action to reduce the availability, attractiveness and affordability of alcohol.

No one thinks that there is one policy that will eradicate a complex problem, but, as with the sugar tax, we should be able to expect a noticeable improvement from a policy that costs us many millions of pounds. That doesn't seem to be happening and so the goalposts are being moved and all the grand promises are gradually being buried.

There was never any chance of minimum pricing being repealed. If it fails, its failure will be used as an excuse to raise the price and add a range of new taxes and bans to the mix.

Sunday, 28 April 2019

In denial about childhood 'obesity'

The European Congress on Obesity kicks off today. It traditionally produces plenty of media-friendly stories based on unpublished research and eccentric opinions. Last year, for example, one of the speakers recommended that fat people be allowed to start work later than everybody else. It also produces a reliable stream of unreliable obesity forecasts.

The first big press release for this year's event led to news stories like this...

Parents are 'in denial' over childhood obesity with 54% underestimating how overweight their boys and girls are

Scientists have accused parents of being 'in denial' over their child's obesity as fresh evidence suggests that more than half underestimate their offspring's weight issues.

But doctors and even the child itself are also guilty of misjudging whether they are overweight, the research found.

This is not really news. You can find similar results if you dig into the tables of the Health Survey for England. If you ask the mothers of 'obese' children, 47 per cent of them will tell you that they are 'about the right weight'. This rises to a whopping 90 per cent when it comes to children who are classified as 'overweight'.

The figures are similar for fathers. Only 46 per cent of them think their 'obese' children are 'too heavy' and only 13 per cent believe that their 'overweight' child is overweight.

The Health Survey for England doesn't ask children for their opinion but it used to. And, when it did, it found that only around a third of 'obese' kids thought that they were too heavy and only 15 per cent of 'overweight' kids thought they were overweight.

We are supposed to believe that all these parents and children are deluded. Even doctors, it seems, cannot identify an obese child. Professor Helen Stokes-Lampard, chairwoman

of the Royal College of GPs, says:

'This study shows how underestimation is prevalent across the board - including amongst healthcare professionals - and highlights the importance of taking accurate measurements, so that appropriate and consistent interventions can be implemented to support a child to lose weight and live a healthier lifestyle.'

But it's not a question of taking 'accurate measurements'. The question is about how those measurements are used. As I have explained time and again, the justification for setting the threshold for child obesity at the 98th percentile is very shaky. The justification for dropping it to the 95th percentile when gathering national statistics is non-existent. It creates millions of false positives.

Parents and doctors have an advantage over researchers who only look at obesity through spreadsheets. They have actually seen these children in the flesh and there is a simple reason why they do not think that many of them are obese. It's because they are not obese.

The facts that healthcare professionals would not diagnose large numbers of 'obese' kids as obese is a giveaway. You can imagine some parents having a rose-tinted view of their children, but not clinicians. Doctors use the 98th percentile because that is the clinical definition. The people at the European Congress on Obesity use the 95th percentile, presumably because it produces a bigger number. They also use the truly ludicrous 85th percentile to define 'overweight'. Neither measure has any scientific credibility.

It is a sham and these people have got some nerve accusing parents and clinicians of being 'in denial' when all they are doing is seeing things as they are.

Tam Fry, chairman of the National Obesity Forum, said: 'Millions of parents are in denial about their own and their children's weight and they are doing their kids no favours at all since, as the researchers point out, they are denied the help to prevent them spiralling into becoming seriously overweight or obese.'

There's only one group of people who are in denial here, Mr Fry.

Thursday, 25 April 2019

Imaginary intolerances and stupid food fads: the world needs The Angry Chef

First published by Spectator Health in July 2017

The Angry Chef: Bad science and the truth about healthy eating by Anthony Warner

I am not very interested in food, which is to say I am no

more interested than someone who eats it needs to be. I’ve been

fortunate enough to have been taken to some fine restaurants in my time,

but I have never been served anything that can compete with a chicken

bake from Greggs. Cooking is boring and if it was possible to live

without eating, I wouldn’t really miss it. It gets in the way of

drinking and then you have to wash up.

I don’t understand why people watch cakes being baked on

television, but I understand that this is a popular form of

entertainment. I am also aware that health and wellness bloggers exist,

but I have also assumed they are spivs and/or idiots and have never read

their work. And whilst I am theoretically sympathetic towards people

who harm themselves as a result of believing nutritional crackpots, a

large part of me thinks that they are narcissistic fools who have

brought it on themselves.

Consequently, I’ve never heard of most of the people in this

book. I had no idea that people turned to Gwyneth Paltrow for

nutritional advice. Why would anybody do that? My only real interest in

nutritional gobbledegook is when it starts to influence policy, as it

has in the current hysteria over sugar. Aside from that, these people

can go to hell in an organic, gluten-free handcart, as far as I’m

concerned.

Anthony Warner, having a bigger heart than I, cares a great

deal about this stuff. He really likes food. He even enjoys cooking it.

This is fortuitous for he is a chef. An angry chef. Angry because he

cannot avoid people with imaginary food intolerances and daft beliefs

about nutritional science.

I don’t blame him. Some of the food fads described in this

book are contemptibly stupid. The alkaline diet is particularly

cretinous. Debunkable by anyone with a GCSE in chemistry, it is, as

Warner says, ‘a huge steaming pile of imaginary bullshit’. He has

similarly blunt descriptions of detox (‘a vast bullshit-octopus’), clean

eating (‘a huge and unrepentant tide of nutribollocks’), advocates for

the paleo diet (‘packs of pseudoscience wolves’) and food gurus in

general (‘poorly qualified and unaccountable fools’).

If the fads are united by a common thread, it is a yearning

for purity; for a rural idyll that never was. Mistrustful of science and

anything that is ‘man made’, the nutritional dupes fall for anything

marketed as ‘natural’. The paleo diet explicitly cries out for a return

to an age in which people were in touch with nature, and all the fad

diets seek to flush out the chemicals of the modern world and take us

back to The Garden. It’s all tree-hugging hippy crap, of course. Polio

and syphilis are natural. Vaccines and anaesthetic are man made. Nature

wants us dead.

It would be wrong to see the wellness gurus and their

followers as being totally anti-science. Rather they take a tiny bit of

science and use their feelings to work out the rest. There really is

such a thing as detoxification (from alcohol, for example). There really

are people for whom being gluten-free is more than a quirky

affectation. Too much sugar really is bad for you.

But these people take it all too far. More often than not,

the solution being peddled by the snakeoil merchants is total abstinence

from one or more ingredient. As Warner notes, if you’re feeling lousy,

the chances are that you will sooner or later feel better with or

without the guru’s help (regression to the mean), but it is all too

tempting to credit the guru for your recovery. If you are fat and the

guru tells you to cut out an entire food group, the chances are your

restrictive diet will cause you to consume fewer calories, but rather

than accept the laws of thermodynamics, you may be tempted to attribute

magical fattening powers to specific foods.

Extremism sells. Nobody makes money from telling people to

eat a balanced diet in moderation and do a bit of exercise. We seem

drawn to self-flagellating exercises in self-denial, up to and including

fasting, so long as we are allowed pockets of excess. Yes, you can

gorge yourself on this particular food, say the gurus, so long as you

abstain completely from that particular. It is as if the combination of

gluttony in one area and total abstinence in another adds up to

moderation.

Such diets tend to be difficult to adhere to and fail. It is

mostly harmless stupidity for people with more money than sense,

although it must be rather tedious for those around them. The dark side

comes when the quacks cause people to develop eating disorders or sell

fake cancer cures. When it comes to these charlatans, Warner’s anger is

more than justified.

The Angry Chef deserves to

be widely read. It covers all the bases with aplomb. The world needs a

popular science book to help people tell the difference between science

and opinion, as evidenced by the fact that it is currently being beaten

on the Amazon sales rankings by The Pioppi Diet: A 21 day lifestyle plan which I will be reviewing tomorrow.

There is no childhood obesity epidemic

There is a heartwarming video on Youtube of Jamie Oliver showing a group of children how chicken nuggets are made in an attempt to deter them from eating them. He blends up a gruesome mix of bones, skin and offal, slaps some flour on it and sticks it in the pan. ‘Now,’ he says triumphantly, ‘who would still eat this?’

The look of disappointment on Oliver’s face when every hand goes up is one of the finest images ever shown on television. It never fails to cheer me up.

After watching it for the umpteenth time, I noticed something. None of the children appears to be obese. In fact, it is difficult to spot many obese kids in any of Oliver’s series involving children. Jamie’s School Dinners was filmed at the height of the childhood obesity ‘epidemic’ and yet there was little sign of it in the cafeteria. Fat kids were also surprisingly rare in Jamie’s Return to School Dinners and Jamie’s Dream School. There were one or two, of course – as there always has been – but at a glance there were far fewer pudgy hands, chubby faces and double chins than one would expect in a country where a third of secondary school children are said to be overweight or obese (supposedly rising to 40 per cent in London).

You may have noticed the same thing if you drop your children off at the school gates or flick through the school news in your local paper. You may even be one of the bemused parents up and down the country who receives a letter from school informing you that your seemingly healthy child is borderline obese.

And yet, one in ten kids are classified as obese when they start primary school and one in five are 'obese' by the time they start secondary school. According to the latest figures, 23 per cent of 11-15 year olds are obese. And that’s before we add those who are merely overweight.

These are shocking statistics and we are reminded about them at every opportunity. Organisations like Public Health England repeat the claim that ‘more than a third of children [are] leaving primary school overweight or obese’ like a mantra whenever they have a new anti-obesity wheeze to push. So where are they all?

You can’t see them because most of them do not exist. They are a statistical invention. The childhood obesity figures in Britain are simply not worth the paper they are printed on. The childhood obesity rate is much lower than 23 per cent. Let me explain.

Obesity in adults is easy enough to measure. Body Mass Index (BMI) is weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in metres. A BMI of 30 or more is classified as obese. In theory, the cut-off of 30 is used because this is roughly the point at which being fat increases the risk of premature death, but it also happens to be a round number. A BMI of 25 or more makes you overweight, but this isn’t really based on anything. It is purely a round number.

There are well known problems with BMI, not least the fact that it does not distinguish between muscle weight and fat weight. It is excess body fat that we are interested in and this is best diagnosed by clinical examination, but when that is not possible (as when estimating figures for an entire nation), the BMI system correctly identifies obesity around 80 per cent of time.

But it doesn’t work with children. Kids are not shaped like adults, do not have the same fat/muscle ratio and are growing. They rarely have a BMI over 30. An obese child can easily have a BMI of less than 25. Moreover, obese girls have different BMIs than obese boys.

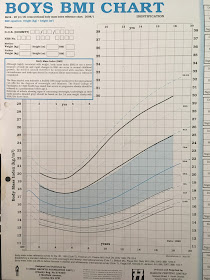

To make up for this, clinicians use a chart like the one below which gives bespoke, age-specific and gender-specific BMI cut-offs for children. For example, at the age of six and a half, boys are considered obese if their BMI exceeds 20.2. By the time the boy is eleven, the cut-off has risen to 25.1.

To see how these cut-offs are derived, we need to look at the work of Professor Tim Cole and his colleagues. In 1995, they published a much-cited study upon which the chart above is based. They studied the BMIs of children at different ages and divided them into percentiles. This allowed clinicians to compare the BMI of their patient to that of their peers. For example, if a girl’s BMI was at the 90th percentile, only ten per cent of her peers had a higher BMI while 90 per cent of her peers had a lower BMI.

The data used by Cole et al. were taken from between 1978 and 1990, before the rise in childhood obesity got underway and gave us a reference point from which future changes in obesity could be measured. For example, if obese 11 year old boys in 1990 had a BMI of 26 and were in the 99th (top) percentile, the obesity rate was one per cent in 1990. To update the statistics, we only need to measure today’s 11 year old boys and see how many of them would have been in the 99th percentile in 1990. If four per cent of them have a BMI over 26, they would have been in the 99th percentile and the obesity rate is four per cent.

This system made it possible to estimate child obesity rates nationwide without clinicians having to examine anybody. Detailed figures have been collected by the UK government since 1995 and all the child obesity estimates published by the NHS and Office for National Statistics are based on Cole’s reference curves from 1990.

It seems relatively straightforward. The problem is that we don’t really know how many children were obese in 1990. Cole’s solution was to infer the rate of child obesity from the rate of obesity among young adults. Common sense dictates that the child obesity and adult obesity figures should ‘link up’, which is to say that both systems should produce similar estimates for young adults. Something would be wrong if 17 year olds had an obesity rate of eight per cent while 18 year olds had a rate of one per cent, especially since BMI tends to rise with age.

Cole et al. noticed that the 20 years olds in 1990 who had a BMI of 29 (and were therefore nearly obese) appeared at the 98th percentile, which is to say that the rate of obesity was a little under two per cent. They also noticed that the 20 year olds in the 99.6th percentile (the top 0.4 per cent) had BMIs of at least 32.8. They therefore concluded that:

‘These centiles seem to be reasonable definitions of child obesity and superobesity respectively.’

They came to a similar conclusion when they published further research in 2000. Looking at BMIs in Britain between 1978 and 1993 (‘predating the recent increase in prevalence of obesity’), they found that obese 18 year olds were at the 99th percentile. In other words, only one per cent of people who had recently become adults were obese by the usual adult definition.

They found similarly low rates of obesity for 18 year olds in the Brazil and Singapore over the same time period. The Netherlands had an even lower rate of 0.3 per cent but the USA had a much higher rate of 3.3 per cent for men and 4 per cent for women.

Taken together, this suggested that the obesity rate among young British adults circa 1990 was less than two per cent and that a realistic cut-off point for childhood obesity was somewhere around the 99th percentile. In a later study, Cole and Lobstein concluded that ‘the obesity cut-off is well above the 98th centile’. It was nevertheless decided to use the 98th percentile, perhaps to err on the side of caution. Whatever the reason it was always likely to exaggerate the scale of child obesity.

Clinicians use the 98th percentile and it is the 98th percentile that is shown in the chart shown above. And yet when we measure child obesity nationally, the government uses the 95th percentile.

Why? There is no justification for it in the scientific literature other than that it is 'the convention'. Cole himself says that the methodology is ‘all built on sand.'

The most likely explanation for dropping the cut-off to the 95th percentile – if we exclude the possibility that it was deliberately intended to exaggerate the size of the problem – is that the USA did it first and we copied them. By the end of the 1990s, the USA had started using the 95th percentile as the cut-off for ‘overweight’, with the 85th percentile used to define ‘at risk of overweight’ – terms that would later be changed to ‘obese’ and ‘overweight’. This was not wholly unreasonable. The rise of obesity in America began earlier than it did in Britain and rates of obesity have always been higher. It is likely that around five per cent of American children were at least overweight, if not obese, by the end of the 1980s and would therefore have been above the 95th percentile.

But Britain is not America. Cole’s figures showed that the obesity rate among 18 year olds in Britain was much lower than it was in the USA – at one per cent – and while he recognised the need for a cut-off, he asked the obvious question:

‘… why base it on data from the United States, and why use the 85th or 95th centile? Other countries are unlikely to base a cut off point solely on American data, and the 85th or 95th centile is intrinsically no more valid than the 90th, 91st, 97th, or 98th centile.’

Whatever the reason for using the 95th percentile, it has had the effect of greatly inflating childhood obesity figures in Britain for as long as they have been recorded. It implicitly assumes that five per cent of 18 year olds were obese in 1990 when we know that the real figure was less than two per cent. Starting from this false premise, everything that follows from it is wrong. Forced to pretend that the child obesity rate in 1990 was more than twice as high as it was, we are given child obesity statistics for the present day that are likely to be off by a similar margin.

We are classifying huge numbers of children as obese who would not have been diagnosed as such by a doctor in 1990 and would not be diagnosed as such today. If you look at the chart above, you will see that the 95th percentile is not even shown on it. It is of no clinical relevance.

The result is that we get figures which defy credibility. Take a look at the latest obesity statistics for adults from the Health Survey for England. The pattern is typical of a developed country, with rates rising steadily as people get older and then dipping in old age.

Now

let’s add the childhood obesity figures which are measured in a totally

different way. As mentioned, they should link up with the adult figures, but they some nowhere near to doing so. Both groups

of children have a higher rate of obesity than the young adults, with

the rate among 11-15 year olds being more than twice as high as that of

16-24 year olds.

To

take these statistics seriously, we have to believe that obesity rises

rapidly in secondary school, affecting nearly a quarter of children,

before suddenly plummeting to barely ten per cent once they

become adults.

It has been suggested that we use the 95th percentile as the child obesity cut-off because the Americans were doing it and we copied them. The USA may well have had a child obesity rate of around five per cent in 1990. As a result, if you look their obesity stats at different ages, there is some sort of gradient. The rates rise with age, albeit with a slightly lower rate at age 12 to 19 than you might expect.

If you take Britain’s obesity figures at face value, we now have a higher rate of childhood obesity than the USA. This is almost certainly untrue. The USA has a much higher rate of adult obesity than Britain (38 per cent vs. 26 per cent). It is almost inconceivable that its rate of child obesity would be lower – you only have to visit the place to see that – but this is what happens when you apply the same relative measure to countries which start from very different places.

A few years ago I gave evidence to an Australian select committee on childhood obesity. I was amazed to hear that their rate of child obesity was just seven per cent. On paper, this is two-thirds lower than Britain’s, despite Australia having a slightly higher adult obesity rate. But once you understand that the method of counting obese children comes from the think-of-a-number school of statistics, it starts to make sense.

As these examples illustrate, using the 95th percentile to define childhood obesity makes it impossible to make meaningful comparisons between different countries. Campaigners who are unaware of this, or who simply don’t care about the facts, breathlessly claim that London has a higher rate of child obesity than New York. It probably doesn't, but we don’t have the data to prove it either way.

In order to make valid international comparisons, the World Obesity Federation – previously known as the International Obesity Task Force – uses international cut-offs devised by Tim Cole and colleagues who looked at children’s body weight in six countries in the 1980s. These international cut-offs allow researchers to make comparisons that are broadly like-for-like. Furthermore, the International Obesity Task Force has always based its definition of obesity on the 98th percentile, as Cole et al. recommended in a series of studies and as clinicians use when diagnosing patients.

The 98th percentile is a more realistic benchmark than the 95th, for the reasons outlined above, but it is still likely to exaggerate the scale of childhood obesity in Britain for three reasons. Firstly, the core assumption in all these estimates is that the proportion of children who were obese in 1990 was the same at all ages. If two per cent of 18 year olds were obese, it was assumed that two per cent of five year olds, ten year old and 15 year olds were also obese. This is an assumption of convenience which leads to over-counting. It is almost certain that obesity rates will be lower among children than among 18 year olds and that obesity rates among children rise with age.

Secondly, children tend to put on weight before a growth spurt. This renders all child obesity estimates questionable.

Thirdly, Cole et al. found that obese 18 year olds were in the 98.9th percentile in 1990. This is obviously closer to the 99th percentile than the 98th. Since 18 year olds between the 98th and 98.8th percentile were not obese, there is no reason to assume children at these percentiles were obese either.

Using the 98th percentile is therefore likely to capture all the obese cases, but it is also likely to create false positives. It is not perfect, but it has the advantage over the 95th percentile in not being utterly ridiculous. It is the measure used to estimate child obesity rates internationally and it is the measure favoured by the academics who devised the cut-off system in the first place.

When this measure is used, a very different picture emerges. The World Obesity Federations’s figures suggest that the proportion of 10 to 13 year old boys in England who are obese is 4.5 per cent. Among girls of the same age, 5.2 per cent are obese. In another estimate, they find that the obesity rate among 10-11 year olds is 2.8 per cent for boys and 2.1 per cent for girls. These are vastly lower figures than the NHS’s estimates for 11 year olds of 20 per cent and 18 per cent respectively.

This is not to deny that child obesity, like adult obesity, has risen over the years. Comparing today’s figures with those of 1990 shows a rise in children’s BMI, albeit one that peaked in 2004 before going into reverse. But we have no idea how many children are obese because the official statistics do not actually measure obesity. Claims about a quarter, or a third, of children being dangerously overweight are for the birds. The true figures – if they ever emerge – are bound to be much lower than the numbers bandied around in the newspapers.

When British parents are asked about their supposedly obese children, only 52 per cent of them say that they are ‘too heavy’. When it comes to children who are ‘overweight’ – a truly meaningless category based on the 85th percentile – only 11 per cent think they are ‘too heavy’. The children themselves agree. Only 51 per cent of ‘obese’ children and 17 per cent of ‘overweight’ children think that they are too heavy.

Rather than reassess their methodology, obesity campaigners accuse these families of deluding themselves. Parents who reject the diagnosis of an arbitrary and patently flawed mathematical assumption are accused of being ‘no longer able to tell whether their children are overweight’. They are said to be suffering from ‘Goldilocks Syndrome'.

Never mind Goldilocks. The Emperor’s New Clothes is the more appropriate fairy tale analogy here. We are told that obese children roam the streets in vast numbers: one in five 11 year olds, rising to one in three if you include the ‘overweight’. No one can see this many obese kids with their own eyes and yet we go along with the illusion, perhaps assuming that they live elsewhere. If you met most of these ‘overweight’ kids, you would probably agree with their parents that they are not fat. A doctor who examined the ‘obese’ kids would reject the diagnosis of obesity in hundreds of thousands of cases.

There was never any justification for the British government dropping the threshold to the 95th percentile. The result of this error is that at least three out of four children who are currently classed as obese in Britain would not be described as such by a doctor. You would not describe them as obese if you saw them. The system used by our statistics agencies is not fit for purpose – unless the purpose is to vastly inflate the scale of the problem.

This is an edited version of two articles published by Spectator Health in February/March 2018

Wednesday, 24 April 2019

Transport for London spends £1000s making its own ads compliant with the 'junk food' ban

Last month Farmdrop, a woke farmer's market on wheels, had an advert rejecting by Transport for London because it included butter, bacon and other 'junk food'.

If you thought this was the most absurd manifestation of the inherent puritanism of Sadiq Khan's policy, you were wrong. A few weeks ago, I sent TfL a Freedom of Information request, asking them to provide details and costs of any work undertaken to make their own adverts compliant with the new rules.

TfL's adverts only promote public transport but they still have to comply. The documents I received are remarkable. To cut a long story short, they spent more than £16,000 doctoring perfectly inoffensive advertisements to remove any trace of 'unhealthy food'. You can't put a price on totally ineffective anti-obesity policies!

Read the full story at Spectator Health.

PS. Meanwhile, Food Active - a pressure group funded by local authorities - has just launched a campaign to give local authorities the power to introduce the same daft rules elsewhere.

If you thought this was the most absurd manifestation of the inherent puritanism of Sadiq Khan's policy, you were wrong. A few weeks ago, I sent TfL a Freedom of Information request, asking them to provide details and costs of any work undertaken to make their own adverts compliant with the new rules.

TfL's adverts only promote public transport but they still have to comply. The documents I received are remarkable. To cut a long story short, they spent more than £16,000 doctoring perfectly inoffensive advertisements to remove any trace of 'unhealthy food'. You can't put a price on totally ineffective anti-obesity policies!

Read the full story at Spectator Health.

PS. Meanwhile, Food Active - a pressure group funded by local authorities - has just launched a campaign to give local authorities the power to introduce the same daft rules elsewhere.

Tuesday, 23 April 2019

Worms addicted to mango flavoured poison (plus nicotiiiiiiiiiine)

Whenever you think the USA's anti-vaping fanatics have reached their limits, they find new depths to plumb. This, from the ironically named and state-funded "Truth Initiative", is something else.

I am lost for words. Just watch the video.

Because they contain heavy metals and residual nicotine, e-cigarettes/pods can qualify as both e-waste and biohazard waste. Definitely not something to toss on the ground, but people do and it’s “sending Earth to hell in a pod-shaped coffin." https://t.co/mMyvBrPv6Q #EarthDay pic.twitter.com/BT4O7e6yAL— Truth Initiative (@truthinitiative) April 22, 2019

Thursday, 18 April 2019

Campaigners push for the most extreme version of bottle deposit scheme

It seems that the campaign for a bottle deposit scheme has already reached the reductio ad tobacco stage...

The question here is whether a deposit scheme should include smaller cans and bottles (up to 500ml) which tend to be binned when people are out and about or whether it should include larger containers which are generally collected and recycled via kerbside collection.

There's a lot to unpick...

Firstly, it seems that it is not enough for these campaigners to lobby for the most extreme form of an inefficient system. Everybody else must do so too - or else. Put aside your misgivings and say something don't believe or you will be cancelled.

Secondly, I can't see the public demonising supermarkets just because they don't think large bottles should be in a deposit scheme. On the contrary, if Deborah Meaden gets her way and we have to start carting empty 3-litre bottles to collection points along with the smaller 'on the go' bottles that were the original target of this campaign, people might wish the government had listened to their concerns.

Thirdly, what has this got to do with the Marine Conservation Society? Michael Gove has promoted a bottle deposit scheme as a way to tackle plastic pollution in the oceans, but it is unlikely to have any measurable impact on it. As I mentioned in my IEA briefing paper, ten rivers transport 88-95 per cent of all the plastic found in the oceans. Eight of them are in Asia. The other two are in Africa. DEFRA barely mentions ocean pollution in its impact assessment. It is a red herring.

Fourthly, I'm not sure why the campaigners are focusing on supermarkets. Various industries have concerns about the scheme while others, like Coca-Cola, support it. As far as I can tell, the main concern of supermarkets is that reverse-vending machines will take up valuable space in their stores. That is a reason for them to oppose a bottle return system. It is not much of a reason for them to oppose a deposit scheme that excludes certain sizes of container. In for a penny, in for a pound.

The people who are most concerned about expanding the scheme to include large bottles are small retailers who will be required by law to set up manual collection points in their shops. The likes of Deborah Meaden don't mention them, presumably because it would be bad optics for a multi-millionaire to be threatening small shopkeepers. The government has also ignored them, but it is worth reading what the Association of Convenience Stores have said to get an idea of the range of unintended consequences that they will have to deal with.

The ACS has serious concerns about time, space and hygiene which the government has not addressed. Many shops simply do not have the room to store a load of dirty cans and bottles which will be buzzing with flies in the summer. This problem will be even worse if the government forces them to take back large wine bottles and two litre bottles of pop - which, to repeat, are already being collected at the kerbside.

Consumers will have to do much the same thing. They will also have to transport the containers to the queue for a reverse-vending machine or manual collection point. They - you - are the other stakeholder that is being overlooked. You only need to picture your own household to see the futility of including large bottles in the scheme. How many times have you bought a three litre bottle of something and deposited it in a street bin? How many times have you thrown such a bottle down in a street or park?

Probably not many. These containers are overwhelmingly used in the home and are recovered (and recycled) via kerbside collection. There is virtually nothing to be gained from making you store these bottles at home, piling them into the car and taking them to a collection point. The only benefit will be to the companies that make the machines because they'll be able to flog the government more complicated, and thus more expensive, equipment.

The Daily Mail article quoted above continues with a typically misleading statistic:

The 'four in ten' figure is simply wrong, but even if it were correct it would be wrong to compare it to the figures from Norway and Germany because the first figure relates to all plastic bottles while the second relates to single-issue plastic drinks bottles. As I said in my briefing...

The idea that a deposit scheme will increase recycling rates from 40 per cent to 90 per cent is for the birds. It is only going to affect drinks containers and DEFRA's own impact assessment expects an increase from the current 72 per cent to around 85 per cent. That is all well and good. The question is whether that relatively small change is worth spending £800 million a year and forcing the public to carry out £1.7 billion worth of unpaid labour for.

I don't see how it can be, and DEFRA's impact assessment resorts to some very dodgy economics to make it appear even marginally cost-effective. But the case for including large containers is blindingly, crashingly, patently non-existent. It's a shame we don't have figures showing the percentage of large bottles that is currently being recycled, but I bet it is an overwhelming majority. Including them in a deposit scheme would place a quite unnecessary burden on shoppers and shopkeepers alike.

But this is what happens with public consultations. When the government puts forward a range of options, single issue fanatics focus on the most extreme scenario and accuse the government of a 'U-turn' and 'buckling to lobbying' if it chooses to do anything less.

Supermarkets have been warned they will be demonised alongside tobacco and oil firms if they fail to back a deposit and return scheme for plastic drinks bottles and cans.

The Marine Conservation Society, backed by Dragons' Den star Deborah Meaden, says only a fully comprehensive scheme covering all sizes of plastic drinks bottle, as well as cans and glass bottles, will tackle waste, litter and pollution.

The question here is whether a deposit scheme should include smaller cans and bottles (up to 500ml) which tend to be binned when people are out and about or whether it should include larger containers which are generally collected and recycled via kerbside collection.

There's a lot to unpick...

Firstly, it seems that it is not enough for these campaigners to lobby for the most extreme form of an inefficient system. Everybody else must do so too - or else. Put aside your misgivings and say something don't believe or you will be cancelled.

Secondly, I can't see the public demonising supermarkets just because they don't think large bottles should be in a deposit scheme. On the contrary, if Deborah Meaden gets her way and we have to start carting empty 3-litre bottles to collection points along with the smaller 'on the go' bottles that were the original target of this campaign, people might wish the government had listened to their concerns.

Thirdly, what has this got to do with the Marine Conservation Society? Michael Gove has promoted a bottle deposit scheme as a way to tackle plastic pollution in the oceans, but it is unlikely to have any measurable impact on it. As I mentioned in my IEA briefing paper, ten rivers transport 88-95 per cent of all the plastic found in the oceans. Eight of them are in Asia. The other two are in Africa. DEFRA barely mentions ocean pollution in its impact assessment. It is a red herring.

Fourthly, I'm not sure why the campaigners are focusing on supermarkets. Various industries have concerns about the scheme while others, like Coca-Cola, support it. As far as I can tell, the main concern of supermarkets is that reverse-vending machines will take up valuable space in their stores. That is a reason for them to oppose a bottle return system. It is not much of a reason for them to oppose a deposit scheme that excludes certain sizes of container. In for a penny, in for a pound.

The people who are most concerned about expanding the scheme to include large bottles are small retailers who will be required by law to set up manual collection points in their shops. The likes of Deborah Meaden don't mention them, presumably because it would be bad optics for a multi-millionaire to be threatening small shopkeepers. The government has also ignored them, but it is worth reading what the Association of Convenience Stores have said to get an idea of the range of unintended consequences that they will have to deal with.

“You’ve got someone wanting £5 on a Paypoint, 20 king-size, a bottle of Buckfast, and, oh, ‘here’s a bag of empty milk bottles’. You have to sort them, scan them. You could not do it. It’s ludicrous. There’s three of four people standing in a queue, they’ll walk away. Speed of service is key thing and you would lose your customers.”

“We are fighting for every space inch of space. If someone comes in with a black bag of plastic bottles, where are you going to keep this stuff?”

“I don’t have room in any of my stores. It’s filled with stock or cardboard to go back. There isn’t the room.”

The ACS has serious concerns about time, space and hygiene which the government has not addressed. Many shops simply do not have the room to store a load of dirty cans and bottles which will be buzzing with flies in the summer. This problem will be even worse if the government forces them to take back large wine bottles and two litre bottles of pop - which, to repeat, are already being collected at the kerbside.

Consumers will have to do much the same thing. They will also have to transport the containers to the queue for a reverse-vending machine or manual collection point. They - you - are the other stakeholder that is being overlooked. You only need to picture your own household to see the futility of including large bottles in the scheme. How many times have you bought a three litre bottle of something and deposited it in a street bin? How many times have you thrown such a bottle down in a street or park?

Probably not many. These containers are overwhelmingly used in the home and are recovered (and recycled) via kerbside collection. There is virtually nothing to be gained from making you store these bottles at home, piling them into the car and taking them to a collection point. The only benefit will be to the companies that make the machines because they'll be able to flog the government more complicated, and thus more expensive, equipment.

The Daily Mail article quoted above continues with a typically misleading statistic:

Currently, only around four in ten of the estimated 35million plastic bottles and 20million aluminium cans used across the UK every day are collected and recycled. The rest are either buried in landfill, burned for energy or end up as litter.

By contrast, recycling rates of more than nine in ten are achieved in other European countries with full deposit return schemes, such as Norway and Germany.

The 'four in ten' figure is simply wrong, but even if it were correct it would be wrong to compare it to the figures from Norway and Germany because the first figure relates to all plastic bottles while the second relates to single-issue plastic drinks bottles. As I said in my briefing...

The charity RECOUP says that 59 per cent of plastic bottles are recovered from households, and the recycling company SUEZ quotes a figure of 57 per cent. Both these figures include containers such as shampoo and milk bottles which would not be affected by a DRS and should not be compared with the figures shown above which are for beverage containers only.

This can cause confusion, such as when the BBC reports that ‘In Norway, 95% of all plastic bottles are now recycled, compared with England at the moment where the rate is 57%’, or when the Guardian claims that ‘Recycling rates for plastic bottles stand at 57%, compared with more than 90% in countries that operate deposit return schemes’.

These are apples and oranges comparisons. The recycling rate for plastic drink bottles is 74 per cent in the UK and 95 per cent in Norway - and Norway is exceptional. Parts of the USA, Canada and Australia, which have had a DRS in place for many years, have recovery rates that are similar to - or lower than - the UK.

The idea that a deposit scheme will increase recycling rates from 40 per cent to 90 per cent is for the birds. It is only going to affect drinks containers and DEFRA's own impact assessment expects an increase from the current 72 per cent to around 85 per cent. That is all well and good. The question is whether that relatively small change is worth spending £800 million a year and forcing the public to carry out £1.7 billion worth of unpaid labour for.

I don't see how it can be, and DEFRA's impact assessment resorts to some very dodgy economics to make it appear even marginally cost-effective. But the case for including large containers is blindingly, crashingly, patently non-existent. It's a shame we don't have figures showing the percentage of large bottles that is currently being recycled, but I bet it is an overwhelming majority. Including them in a deposit scheme would place a quite unnecessary burden on shoppers and shopkeepers alike.

But this is what happens with public consultations. When the government puts forward a range of options, single issue fanatics focus on the most extreme scenario and accuse the government of a 'U-turn' and 'buckling to lobbying' if it chooses to do anything less.

Monday, 15 April 2019

A load of old rubbish

I want to talk to you about bottle deposit schemes.

No, come back. It's more interesting than it sounds. Michael Gove wants us to take our empties to one of 34,000 reverse-vending machines because it will help save the turtles or something. It's not going to save any turtles and it is a fantastically expensive way of achieving very little.

Still, it sounds like a nice idea and so it will probably happen. It seems to have worked quite well in some other countries so there seems no reason not to adopt it in the UK. This is faulty reasoning. The deposit scheme is a classic example of a feel-good policy that fails basic economic analysis.

The government's own economic analysis is a bit of a joke, as I explain in an article for Spiked today...

This is patently not cost-effective, and so DEFRA conjures up nearly £1 billion of intangible benefits while overlooking the huge amount of unpaid labour that will be required to make the system function. The impact assessment is hopelessly skewed towards finding a net gain.

Whether your objective is reducing marine pollution or reducing street litter, the huge sums of money that will be spent on this make-work scheme could be better used in so many ways. Britain already recycles 74 per cent of plastic drinks bottles, which is more than some places that have a deposit scheme. There is room for improvement but most of the bottles that go unrecycled are used out of home and could be recovered if better street bins were available.

Layering a deposit system on top of kerbside collection makes no economic sense. It just adds to the workload. (This is the big difference between the UK and most countries that have deposit schemes - the latter didn't have kerbside recycling when their deposit schemes were introduced.)

You only have to subject the policy to normal cost-benefit analysis to see that it makes little sense. That is what I have done in this IEA briefing paper.

Read the rest of my Spiked piece here.

No, come back. It's more interesting than it sounds. Michael Gove wants us to take our empties to one of 34,000 reverse-vending machines because it will help save the turtles or something. It's not going to save any turtles and it is a fantastically expensive way of achieving very little.

Still, it sounds like a nice idea and so it will probably happen. It seems to have worked quite well in some other countries so there seems no reason not to adopt it in the UK. This is faulty reasoning. The deposit scheme is a classic example of a feel-good policy that fails basic economic analysis.

The government's own economic analysis is a bit of a joke, as I explain in an article for Spiked today...

Could a bottle-deposit scheme make a difference to marine pollution? On the margins, perhaps, but DEFRA doesn’t seem to have high hopes. Reading its impact assessment, the first thing that struck me was that it barely mentions the ocean and only alludes to possible ‘further additional benefits’ when it does. This is in stark contrast to DEFRA’s press release and Michael Gove’s op-eds, which talk of little else. One gets the impression that Gove wanted to be seen to be doing something in response to Blue Planet II and came up with an idea that, upon closer inspection, wasn’t going to cut the mustard. Rather than saving the turtles, the impact assessment focuses on the less glamorous objective of reducing street litter.

The second thing that struck me was how damn expensive it is going to be. According to DEFRA, it will require 35,000 reverse vending machines to be installed around the country and a new quango – the Deposit Management Organisation – to be created. Small retailers will be required by law to turn themselves into manual take-back points, with minimal remuneration. The system is expected to cost over a billion pounds in its first year, with ongoing costs of £814million per annum. The government expects this to be paid for by consumers who don’t return their drink containers and by producer fees charged by the Deposit Management Organisation. Either way, it means higher prices for consumers.

Even under DEFRA’s somewhat optimistic assumptions, the financial returns from this system are meagre. It expects to collect extra recyclable material worth £37million, reduce litter collection costs by £50million and produce ‘greenhouse-gas emissions savings to society’ worth £12million. The estimate for litter collection looks high, but even if it is accurate, the system will make less than £1 for every £8 spent.

This is patently not cost-effective, and so DEFRA conjures up nearly £1 billion of intangible benefits while overlooking the huge amount of unpaid labour that will be required to make the system function. The impact assessment is hopelessly skewed towards finding a net gain.

Whether your objective is reducing marine pollution or reducing street litter, the huge sums of money that will be spent on this make-work scheme could be better used in so many ways. Britain already recycles 74 per cent of plastic drinks bottles, which is more than some places that have a deposit scheme. There is room for improvement but most of the bottles that go unrecycled are used out of home and could be recovered if better street bins were available.

Layering a deposit system on top of kerbside collection makes no economic sense. It just adds to the workload. (This is the big difference between the UK and most countries that have deposit schemes - the latter didn't have kerbside recycling when their deposit schemes were introduced.)

In layman's terms, the question here boils down to: 'Does a modest reduction in littering justify spending £814 million a year and forcing tens of millions of people to take their empty drink containers to a recycling station when 72 per cent of these containers are already being recycled and kerbside collection covers 99 per cent of British households?'

This question can only be answered in the affirmative if you put a huge value on the cost of littering and no value on people's time. That is essentially what DEFRA has done and I can see no justification for it. You can't throw the normal rules of cost-benefit analysis out of the window just because an idea sounds nice - and no amount of talking about turtles is going to change that.

You only have to subject the policy to normal cost-benefit analysis to see that it makes little sense. That is what I have done in this IEA briefing paper.

Read the rest of my Spiked piece here.

Saturday, 13 April 2019

Minimum pricing - a brief overview

I've written an introduction to minimum pricing for Freer.

Have a read of it.

If a minimum price of 50p is ‘evidence-based’, then what would a minimum price of 60p or 70p be? The Sheffield model suggests that a 70p unit price would be more effective in reducing alcohol-related harm than a 50p unit price. Presumably, a £3 unit price would ‘work’ even better, but nobody is seriously calling for it. Why? Because it would increase the cost of living and make drinking unaffordable for many people. But so does a 50p unit, and it is easy to detect of element of snobbery here. It is deemed acceptable to increase the cost of living for people who tend to buy cheap alcohol, but not for those who can afford more expensive brands. MUP targets off licence beer while leaving the price of champagne untouched.Drinking is not illegal, nor is it illegal to exceed the government’s gerrymandered guidelines. Insofar as there are external costs associated with alcohol consumption, they are comfortably exceeded by alcohol duty revenues. MUP is a shamelessly paternalistic and patently regressive policy. Unnecessary and seemingly ineffective, it has no place in a free society.

Wednesday, 10 April 2019

Have the health benefits of drinking been disproved?

A study in the Lancet got a lot of media attention last week because it purported to disprove the health benefits of moderate drinking. No single study can do that, of course, but that's how it was reported. It was accompanied by an astonishing editorial calling for readers to 'Unite for a Framework Convention on Alcohol Control' next to the 'no smoking/drinking' image shown above. No slippery slope, eh?

In short, the study looks at a Chinese population and argues that the J-Curve showing lower levels of stroke risk for moderate drinkers is an artifact of genetic differences. Two genotypes - ALDH2-rs671 and ADH1B-rs1229984 - are identified as suspects. The problem is that the former 'is mainly absent among Europeans but is prevalent in populations in East Asia' and the latter 'is found in 19 to 91% of East-Asians and 10 to 70% of West-Asians, but at rates ranging from zero to 10% in other populations'. Since most of the evidence for the J-Curve comes from western countries, it is not at all obvious that this explanation would hold up outside of Asia.

I was in Belgrade for LibertyCon when the study was published and didn't have time to look at it in detail. In any case, I don't pretend to be an expert on Mendelian randomisation, which is what the findings rely on, and its authors aren't likely to win any awards from the Plain English Campaign.

So here instead is the view of Christopher Oakley who has kindly written a guest post...

It is clear to anyone who has being paying attention to the shenanigans of the public health industry that the new Holy Grail for this pseudoscience is finding “proof positive” that the protective effects of moderate alcohol consumption are a myth. This is crucial to the more extreme elements that sadly dominate the discourse because, in their minds, it removes the last barrier to treating the alcohol industry as they have the tobacco industry and “denormalising” drinkers the way they have smokers.

Most of the attempts to do this have been exposed as pseudoscientific window dressing for puritanical agendas but last week’s effort involved some real science for once.

A study performed in China looked at people with genetic variants that reduce alcohol consumption. There are two genes involved so nine possible combinations of genotypes with a range of effects from making drinking alcohol very uncomfortable indeed to not having much effect at all. By looking at these groups it is possible to study incidence of stroke and heart disease relative to genotype and therefore ability to consume alcohol. Not a bad idea as it cuts out the reliance on what people say they drink and other confounders that make many epidemiological assertions equivalent to claiming to have split the atom with a bread knife.

The normal process for revealing a novel technique or discovery in science is to rigorously test prior to publishing in the most prestigious journal possible, defend it in peer review, modify if needs be and eventually, perhaps inform the wider public. But public health isn’t science. It has agendas and rushes to publicise anything that supports them, often avoiding prestigious focussed journals by publishing in medical journals with low standards but high media profiles.

So, unfortunately the world was made aware of this novel approach courtesy of uncritical journalism based on a press release issued by The Lancet that begins:

The Lancet: Moderate alcohol consumption does not protect against stroke, study shows

Blood pressure and stroke risk increase steadily with increasing alcohol intake, and previous claims that 1-2 alcoholic drinks a day might protect against stroke are dismissed by new evidence from a genetic study involving 160,000 adults.

Dismissed is a strong word in academia that should have given the journalists a further clue that this was a less then impartial perspective. An even bigger clue comes in the penultimate paragraph, which reads:

Writing in a linked Comment, Professor Tai-Hing Lam and Dr Au Yeung, from the University of Hong Kong…call for a WHO Framework Convention for Alcohol Control (FCAC), similar to the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC): “Alcohol control is complex and stronger policies are required. The alcohol industry is thriving and should be regulated in a similar way to the tobacco industry.”

So, a novel scientific approach that should be cautiously rolled out open to question and peer discussion is rushed into the public domain with sensational claims linked to a call to arms aimed at fans of industry / lifestyle hyper regulation. And the BBC didn’t think to question this? Or read the study?

The rest of the press release talks about the study in brief detail but ignores an important section for reasons those of us familiar with the ethics of The Lancet and the lifestyle public health industry are all too familiar with.

The new approach of genetic epidemiology was performed alongside a larger conventional epidemiology study which produced very different results.

The conventional epidemiology produced the familiar J-shaped curve with non-drinkers and ex-drinkers having risk of stroke equivalent to people consuming around 25-30 units per week, which is consistent with many similar studies. The genetic epidemiology, by contrast, shows a steady increase in risk with consumption.

Thanks to the laziness (or prejudice) of journalists and the selective briefing from The Lancet, most people, including those who make our laws will be blissfully unaware that the contradictory conventional results exist. I don’t think that is accidental.

But why the difference in results? The authors of the paper are more circumspect than the press release but understandably talk up their genetic approach. They don’t offer any real explanation other than 'reverse causation and confounding', which is a feeble argument when you have segregated non-drinkers from ex-drinkers. If it were true, all of the lifestyle epidemiology that we have been bombarded with for decades becomes highly questionable.

Mendelian randomisation does have benefits provided that the assumptions made are correct. However, the implementation in this case also has downsides and I have listed the pros and cons in the table below.

The great strength of the genetic approach is that it cuts out a lot of uncertainty around misreporting and other human confounding problems that bedevil conventional epidemiology, but the great weakness is that it doesn’t link individual drinking patterns to risk.

The genetic study calculates mean consumption for each genotype in each area and assigns it to all participants in that group. This is a big departure from conventional epidemiology in which individuals are asked how much they drink. In this study, everyone has the same predicted consumption and therefore risk, irrespective of their actual consumption.

That is OK if you are wanting to show that genotype mediated capacity to drink is linked to increased risk of stroke or that stroke risk increases with consumption at the population level. It is less than fine if you are trying to claim that “one drink a day increases stroke risk” because you have no idea what is happening to individuals within groups, and sub populations can introduce bias.

In this case matters are made worse by not segregating non-drinkers, higher risk drinkers and ex-drinkers from current drinkers. If we ignore the controversial non-drinkers and look at the composition of the six genetic groups with a focus on group C4, which is a proxy for moderate drinkers in conventional studies, this is what we get:

So, in the moderate drinker proxy group, the two most risky categories from conventional epidemiology are represented in almost equal numbers as moderate drinkers and considerably outnumber those drinking within UK government guidelines.

The C4 group also included 12% non-drinkers and 48% occasional drinkers who were assigned a 0.5 unit (5g) weekly consumption. The net effect of that is to significantly reduce the mean for the group to the extent that it does not realistically represent consumption for current drinkers.

One of the very concerning features of this study is that the authors seem over-eager to promote some contentious aspects but dismiss or ignore others. For example, the genetic study implied that around 10% of total strokes can be attributed to alcohol, double what is expected from the apparent impact on blood pressure. Rather than question the numbers, as any good scientist using a novel methodology would, the authors airily hypothesise why they are correct and then mass publicise them courtesy of The Lancet.

If they are correct, we might expect to see some impact on regional stroke incidence but there is none. At the study extremes, the province of Gansu, where drinking incidence is lowest, has a higher incidence of stroke than Sichuan where consumption is over 12 times higher.

Overall, I think that the use of Mendelian regression to reduce confounders is a positive for this study but the authors have been far too keen to make the data fit their preconceptions and have introduced their own confounders through their methodology. I do not believe that the study justifies the claims made by The Lancet and echoed in the media.

I find it frustrating that the mainstream media cannot understand that melodramatically embargoed prejudiced press releases from scientifically and ethically questionable sources should be treated with suspicion. Until they do, their output will be distrusted by an increasing number of people who will look elsewhere for news. In some areas, particularly health, it is practically impossible to distinguish the output from the established media from the “fake” news online.

An indication that this is a problem can be seen in the top-rated comments under the superficially balanced but embarrassingly uncritical and preachy BBC article on this study.

“Calm down and wait a few minutes, another expert theory will be along soon”

“Reading all these horror stories about alcohol consumption has given me the wakeup call that I need. It's time to give up reading”

“I wish they'd make their minds up. The warnings mean nothing when they change so often”

“Living one more day increases the risk of stroke”

“Can we please have the original statistic? Saying there is 10 - 15% increase is meaningless without the starting amount. A 15% increase on a risk amount of 0.005 is a tiny amount. A 15% increase on 50 is huge”

“Bored now. Please keep your ever changing health advice to yourselves”

So, not exactly a ringing customer endorsement of public health output, BBC editorial policy and its journalism. But they are not entirely to blame. It would help enormously if CRUK, BHF and the MRC stopped supporting ideological crusades and did something more useful with our money. After all, somewhere between 90% and 100% of strokes are nothing to do with alcohol.

Tuesday, 9 April 2019

Minimum pricing still failing

Minimum pricing was supposed to reduce alcohol sales in Scotland by 3.5 per cent in its first year. Politicians and campaigners left us in no doubt that it would reduce consumption. Alas, with nine months of sales data now available, the previously reported increase has been confirmed...

Scots are drinking more despite minimum pricing

Scots have bought more alcohol since minimum pricing laws came into force, an analysis has found.

Nielsen, a data specialist company, found that 203.5 million litres of alcohol was purchased from shops in Scotland over the 46 weeks to March 29, an increase of 1.8 million litres — the equivalent of four million cans of lager or 2.4 million bottles of wine — on the same period in 2017-18, according to The Mail on Sunday.

The article doesn't say what the change in units (as opposed to volume) is, but the IRI figures I've seen show a two per cent increase in alcohol units purchased since then end of April 2018 (IRI uses the same methodology as Nielsen).

As expected, there has been a big, double-digit decline in cider and perry which has been more than compensated for by a surge in spirits, ready-to-drink (RTD) and fortified wine. Beer sales have also risen.

It now seems almost certain that the campaigners-turned-evaluators (this is the 'public health' racket we're talking about here) won't be able to claim any decline in alcohol consumption in the first year. Nevertheless, the state-funded temperance group Alcohol Focus Scotland is strangely optimistic:

Alison Douglas, the chief executive of Alcohol Focus Scotland, said she was confident that further evaluation would show “minimum unit pricing delivers clear benefits”.

I bet she is. The studies might as well have been written before the policy was implemented. Unable to show an actual decline in consumption, the evaluators at Sheffield and Stirling Universities (for it is they) will have to resort to using a back-of-the-envelope counterfactual which will doubtless conclude that consumption is lower than it would have been in the absence of minimum pricing.

This will then be presented to the media as a decline and the policy will be declared as a success, albeit with the caveat that the unit price should be raised to 60p.

It remains to be seen whether the public will swallow any of this. Minimum pricing is costing Scottish consumers tens of millions of pounds. It is one thing to accept this as the cost of reducing alcohol consumption, but shelling out large quantities of cash to increase consumption by a bit less than a theoretical model suggests it might have increased by is a harder sell.

Incidentally, I hear that the Scottish government is running a heavy anti-alcohol advertising campaign focusing on the drinking guidelines, presumably in the hope that 'education' will succeed where minimum pricing seems to be failing.

Friday, 5 April 2019

Freedom is slavery

The latest hot take from the neo-prohibitionists...

I beg your pardon?

Er, OK. And who are these imbeciles?

You won't be surprised to hear that the European Network for Smoking and Tobacco Prevention is one of the EU's numerous tax-sponging anti-freedom outfits. Under their watch, there will be no smoking, regardless of how many people want to smoke.

They are now trying to turn their desire to remove your right to smoke into a rights issue. I guess their right to tell you what to do trumps your right to decide how you live your life.

Insofar as there is logic to this, it is that there is a right to health and smoking is bad for your health, therefore you are violating your human rights if you smoke. Aside from this being obviously nonsensical, the same could be said of any activity that carries a risk, of course, but the idea that people have competing goals and make trade-offs between their 'rights' doesn't seem to have occurred to these fanatics.

A right to health is not the same thing as an obligation to be optimally healthy. A right to life means that people aren't allowed to kill you. It doesn't mean you have to do everything within your power to extend your longevity.

In an effort to give their ridiculous ideas some legs, the anti-smokers held a conference in Romania recently. The Global Forum on Human Rights and a Tobacco-Free World was co-organised by the US branch of ASH. They, too, have stopped bothering to deny that they are prohibitionists.

ASH USA is run by Laurence Huber...

Fancy that!

If that doesn't give you an idea of the kind of people we're dealing with, try this tweet from the conference...

There was a time when that kind of comment would draw the attention of men in white costs. Nowadays it gets you a fat grant from the EU or an award from the WHO. Personally, I prefer the old days.

Smoking is slavery and against human rights, activists say

Smoking is a form of slavery and is completely incompatible with widely recognised human rights, activists against smoking have said.

I beg your pardon?

They also criticised the so-called novel tobacco products for muddying the waters with the claims of being “much less harmful”

Er, OK. And who are these imbeciles?

“I am absolutely convinced that smoking is slavery and it goes against the human right for life and health. We should engage our work with activists in the human health field,” Francisco Rodriguez Lozano, president of the European Network for Smoking and Tobacco Prevention (ENSP) told EURACTIV.